Hello! Goodbye! American Ballet Theatre’s City Center season came and went with dispiriting speed—seven performances in five days (October 16 through 20). The pleasures outweighed the disappointment. New Yorkers could rendezvous with revivals of three ballets in the company’s history: Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo (1942), Antony Tudor’s The Leaves Are Fading (1977), and Mark Morris’s Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes (1988). Alexei Ratmansky premiered a gorgeous new ballet. And a live orchestra played the music.

Ratmansky’s Symphony #9, set to Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 9 in E-Flat Major, Op. 70, is part of a projected Shostakovich trilogy that will be unveiled during ABT’s Spring 2013 season at the Met. The music has a sad history. In 1944, for unclear reasons, Shostakovich stopped working on the massive piece he was supposed to be writing—something along the lines of Beethoven’s Ninth—to celebrate Russia’s victory over Germany on World War II’s Eastern Front. He replaced it with a very different 9th symphony. In 1948, its bright, clever, sprightly tone was deemed by the Soviet bureaucracy to exemplify frowned-upon formalism and to be ideologically incorrect. It was banned, along with other works by the composer, then finally restored to favor in 1955 (supposedly as the result of an earier phone conversation between Shostakovich and Stalin, during which the latter said something along the lines of “What? Banned? I’ll have to look into that”).

Ratmansky’s non-story ballets are never strictly formal. In sometimes mysterious ways, they project images of community and fragmentary allusions to narrative, character, and occasion that come to him through the music. “Is this a game?” you think, “or did she just die?” And “is this an army drilling, or is it just a pleasing linear pattern for the corps de ballet?” And when the leading male dancer lies down beside his beloved but briefly raises an upward pointing finger, does he mean, “You guys go on without me,” or is he trying to say one last word?

Shostakovich, consciously or unconsciously, may also have buried references to the contemporary atmosphere. His occasional heroic sounds and circusy bombast acquire a buried bitterness via dissonance (the Red Army lost approximately twice the millions of soldiers that the Nazis did in the Eastern campaigns). In the third movement of Ratmansky’s ballet, the women line up along one side of the stage, put their hands over their faces, sit, and drop their heads onto their bent knees. In the symphony’s first movement, the brass instruments’ assertions are several times followed by an impudent piccolo response. You can imagine a Tyl Eulenspiegel thumbing his nose at the establishment.

Ratmansky is brilliant at producing complexity and taming it down just when your eyes need a rest. A skitter of activity in the background, a passing through of some dancers, a foreground spectacle—these resolve into tidy unison before they explode again into orderly dishevelment. The beginning of Symphony #9 is playful. Six men take turns helping each other jump. Craig Salstein races onstage, launches himself into the air, and, whup! he’s reclining on a raft of guys’ arms, eyeing us saucily. The women join, prancing and flying in sideways leaps. Simone Messmer, her boyish haircut not concealed as usual, is their leader. Who has the fastest feet? She and Salstein are made for each other. I’ve always loved his ease onstage and the way he seems able to shrug himself into any style and look as if he owned it. Ratmansky must feel the same way.

Keso Dekker’s costumes—short, sleeveless, full-skirted dresses for the women and sleeveless tee shirts worn with dark, velvety tights for the men—bear bold, irregular patterns in blacks, grays, and browns that look to be silk-screened. The combination of elegance and sportiness is both strange and becoming, and Jennifer Tipton has lit the stage with her usual clarity. The inhabitants could be members of a village with intergalactic connections.

Messmer and Salstein are the spunky ones in this society, but Polina Semionova has moments of capriciousness, and the splendid Marcelo Gomes shows sparks of wit in a duet that suggests melancholy attachment. The two are rarely alone, and in the middle of their dance in the second movement, Herman Cornejo appears. Who is this latecomer? He passes between Messmer and Gomes, joins them, is lifted by two men, just as the “lovers” were a few minutes before. When he leaves, everyone looks baffled. What just happened? Where did he go?

At this point Gomes and Semionova do something strange. They drop suddenly into identical sitting positions and, with equal suddenness, lean sideways and catch their weight on one forearm. Then, plop, they’re lying on their sides, then on their backs. That’s when Gomes raises a cautionary finger. After some more dancing by eight women, Gomes tries to rouse Semionova, without success. She’s limp. Finally, he drags her to her feet so he can carry her away.

Cornejo, as always, is a marvel. Physically gifted, attuned to the music, he fills out every movement without ever over-projecting, or seeming to strain. He weaves through the rich goings-on during the three remaining movements of the music. Finally, when Salstein and Messmer have reappeared, and members of the corps have flown in for brief duets and trios, and many of them have assembled to repeat the jerky descent to the floor that Semionova and Gomes personalized earlier, Cornejo is left alone. One leg held out to the side, he spins and spins—a compass needle searching for true north. He drops to the floor. The end.

All the dancers look wonderful in this ballet. What a gift to them and to ABT’s repertory!

Rodeo was just such a gift (actually, of course, a wise 1950 purchase). Agnes de Mille had choreographed it for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1942, the year before she expanded her western horizons by choreographing Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! on Broadway. At the ballet’s premiere, she danced the role of the tomboy heroine herself, and spunky she must have been in rehearsal. An engaging short documentary film, Rodeo: 70 Years, graced ABT’s opening night gala, and in it she reiterated in old film clips the scenes she described so well in her Dance to the Piper. The largely Russian male members of the Ballet Russe met her bowlegged-in-the-saddle moves with puzzlement and disdain and whimpered for grand jetés. Frederic Franklin, now a spry 98, her partner in the ballet and morale-booster during rehearsals, appeared in the film and in the City Center audience. ABT’s gala occurred on October 16th —70 years to the day from its first performance.

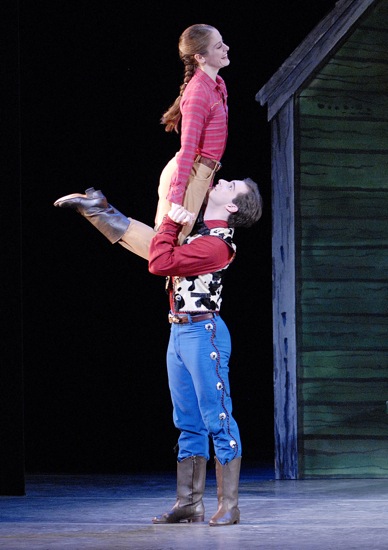

(L to R) Jared Matthews (Head Wrangler), Xiomara Reyes (Cowgirl), and Sascha Radetsky (Champion Roper) in Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo. Photo: Gene Schiavone

If you strip the plot of Rodeo to its skeleton, it tells you that a girl who tried to ride with the cowhands and had a crush on the Head Wrangler found love once she put on a dress. It’s how the story is told that makes it not only a beautifully constructed ballet, but one that’s nuanced in its expressiveness and surprisingly touching. It has a few flaws. One too many times, the Cowgirl’s horse runs away with her, while she—bucking and hauling on imaginary reins—tries to control it. But otherwise, de Mille’s welding of horses and their riders in a down-home rodeo that only neighbors attend gives a fine loping dynamic to the choreography.

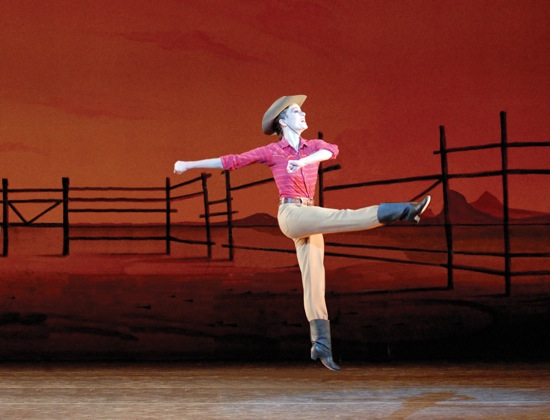

Aaron Copland’s score conveys the same sense of open space that the dancers’ gazes do. Even the dressed-up town girls sense the surrounding plains. When the Champion Roper jogs along the back of the stage—boots tapping, fingers snapping lazily but crisply— against Oliver Smith’s sunset-red sky and lone corral fence and in Thomas Skelton’s dying light, he looks small against the immensity. The scene change to the Ranch House for the dance is covered by a square dance for a single foursome in front of another Smith curtain. No music, just the sound of the dancers’ feet, the occasional yell, and the caller’s commands (Kenneth Easter did the calling at one performance, Eric Tamm at another). It’s a brilliant device.

No problem getting ABT’s dancers—most of them anyway— to look born in the saddle. Jared Matthews was a bit stiff-spined as the Wrangler, but both he and Roman Zhurbin played with convincing charm the role of a handsome fellow who has an eye for the ladies. Kelly Boyd and Lauren Post invested the role of the blonde-ringletted Ranch Owner’s Daughter with sweet flirtatiousness.

The characters you fall in love with are, of course, the Cowgirl and the Roper. She for her gawkiness, stoicism, and forlornness in love. He for his gusto and his kind nature. These people aren’t stereotypes; De Mille made them believable. Xiomara Reyes and Sascha Radetsky performed excellently on opening night. Much credit should go to Paul Sutherland for his coaching. At the second performance, Marian Butler and Salstein took over, and their rapport was wonderful to see. Butler has a gift for looking waifish without trying, and Salstein delivered his actions with no-nonsense zest. I don’t mean just in his show-off tap dance in silence (Radetsky managed his number nicely, but Salstein clearly has chops as a tapper); I’m talking about, say, the firm way he spits on his hands to slick back the stray hairs of his friend the Cowgirl, and tries to advise her when no partner comes her way at the dance (that is, until she goes away and returns in a yellow dress with a bow in her hair to be soundly kissed by him).

Copland’s terrific music—like the achingly beautiful “Saturday Night Waltz” and the “Hoedown”— isn’t all concerned with dancing. He left the pauses that de Mille needed for gestures and actions that have dramatic import (like the moment in which the girl who has been whirled too violently by her partner gradually realizes she’s going to throw up and is rushed away).

Rodeo‘s Saturday Night Hoedown. Far left: Matthews, Reyes (in a dress!), and Radetsky. Photo: Gene Schiavone

ABT’s dancers are expert at capturing choreographic style. Tudor’s The Leaves Are Fading— set to Antonin Dvorak’s Cypress for string quartet and others of Dvorak’s chamber pieces—isn’t one of the choreographer’s great works, and at times you think you’re going to drown in so much prolonged loveliness, but much about it is remarkable. In this work, the choreographer, like Ratmansky and Jerome Robbins, is interested in showing you a community that exists beyond who’s in the spotlight. In their filmy, rose-garden costumes by Patricia Zipprodt, lit softly by Tipton, dancers on the sidelines watch others perform, join in, slip away, seem to converse. The unequal number of men and women allowed Tudor to dream up ingenious ways of people replacing one another in patterns, of taking turns. In the opening section, the eight women and five men, plus a principal couple, let their arms hang quietly at their sides most of the time. Because of this, the lift and turn of their bodies look not just simpler, but more ardent; the women seem to breathe their way onto pointe. The cast I saw was led by Hee Seo—gorgeously, fluidly rapturous— and Roberto Bolle, her smitten partner.

Seo is also marvelous in Morris’s Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes. The ballet is set to Virgil Thomson’s impudent piano Etudes, which bear titles like “For the Weaker Fingers” and “Pivoting on the Thumb.” I’d forgotten how delicious the choreography is—how precise but fluent its patterns and musical sense. Back in 1988, Mikhail Baryshnikov danced the leading male role with Julio Bocca and Robert Hill as foils. Here Cornejo takes Barshnikov’s part, sometimes vying with James Whiteside and other times with Jared Matthews. A tango provides him with a dashing solo.

Santo Loquasto’s draped flesh-toned costumes are handsomely understated, and Michael Chybowski’s lighting is also subtle. Nothing detracts from Thomson’s witty exercises (masterfully played by Barbara Bilach) and Morris’s feast of canons and kaleidoscopic patterns, along with clever movement motifs (like the jumps in which the dancers bent their legs into diamonds and land with a jolt on Thomson’s heaviest beats).

A season that leaves you wanting it to last a bit longer can be considered a success.

Thank you Deborah for your eloquence on Rodeo, a ballet I think of many layers. I’ve always viewed Rodeo as a ballet about an outsider becoming an insider, with feminist undertones. And I was interested in what you say about the “sweetness” of the Rancher’s Daughter, who in some productions I’ve seen has been interpreted as a bit of a bitch.

I’ve just been writing about Loring’s Billy the Kid, for which Copland composed his first score for ballet in 1938, and I’m struck by what you say about the provision of silence for action. It was Copland’s idea for Billy to kill in silence, on the grounds that it would be far more powerful than a musical “gunshot.”

Wish I could see the Ratmansky, but then I always wish I could see any piece so beautifully and graphically described not only by you, but by Tobi Tobias in Seeing Things and Robert Greskovic in the Wall Street Journal.