Pina Bausch’s last work, created in the six months before her death in June 2009, takes its title from a line in a song by the Chilean singer Violeta Parra, who committed suicide in 1967. The dance is called . . .como el mosguito en la piedra ay si, si, si. . . . , and the name of the song is Volver a los 17. What is it that makes us feel 17 again? In the end the song’s refrain, with its evocation of a little patch of moss growing on a stone (and ivy clinging to a wall), reveals its subject. Only love can restore our innocence.

This piece of Bausch’s—unlike almost any other work of hers that I can think of—embodies that nostalgia in its very structure. In the last moments of its two-hour-and-forty-minutes duration, a distillation of several elements winds backward to her first image, as if the dance were preparing to live its life over again. But, of course, there is no new beginning for Bausch, even though the company that she created, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, strives to keep her legacy alive.

It is said that Bausch didn’t know she was dying of cancer until three weeks before she succumbed. But I wonder whether, in some deep part of herself, she had an inkling. . . .como el mosguito. . . has no overarching theme or ambiance as Bausch’s greatest works do. She always created as if she were building a mosaic—selecting bright tiles and fitting them together. But sometimes they formed a whole that both unified and elevated them. This slender last work is more of an anthology—not a collection of previously seen moments, but a collection of the kinds of moments that appear in all Baush’s theater pieces. You cherish this one the way you cherish an album of photographs; they summon up memories that go beyond the actual images we’re looking at.

Each of her late works focuses on a particular country or city to which the company has traveled. Yet this time, few of the eclectic musical selections clearly evoke Chile, the country that spawned it; neither do Peter Pabst’s set or Marion Cito’s costumes (except for one traditional Andean outfit introduced as a joke). We do hear Parra’s song and the sweet, slightly ragged voice of Victor Jara, murdered during the Pinochet regime; too, in Santiago, Bausch’s company rehearsed in the studio of Jara’s widow, Joan, who, like Bausch, had once danced in Kurt Jooss’s company in Essen. Perhaps the retrospective tone of the resulting work owes a little to this meeting.

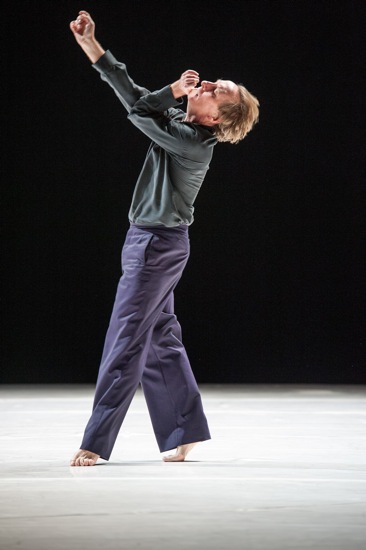

As in almost all of Bausch’s “travelogues,” every one of the splendid performers has a solo (there are only 14 in the cast, half the total number on the company’s roster). These dances vary in length, but all employ a soft, supple, fluid vocabulary, in which the performer’s torso and arms are more elaborately mobile than their legs. Their arms keep wreathing and knotting around their spiraling bodies; often they initiate a movement with a toss of their heads, which makes the women’s long hair lash around them. I especially relish those with the most distinctive qualities, such as the emotionally open, lavish sweep of Dominique Mercy’s dancing (this superb performer, now 62, is, with Robert Sturm, co-artistic director of the company). Or perhaps it’s the piquancy and rhythmic irregularities of Ditta Miranda Jasjfi’s solo that enthrall you, or the odd angularities that creep into Azusa Sayama’s.

Pabst’s set consists of a white floor that seems to be made of large separate pieces; sometimes a few of these slide apart, revealing dark crevices, then grow imperceptibly together again. At one point, a black-and-white film of a wide, turbulent waterfall replaces the black curtains. In this indeterminate evironment, the women wear the long, clinging evening gowns typical of Bausch works and the men a variety of shirts and trousers, with or without jackets.

As usual, Bausch’s wit often skews everyday actions, prolongs them through repetition, or juxtaposes them to unlike ones. Jasfi holds a glass of water; Fernando Suels Mendoza picks her up (she’s tiny), opens his mouth and tilts her so that her entire body becomes the vessel pouring his drink. Thusnelda Mercy (the daughter of Dominique) lies down and spreads her long hair behind her; Rainer Behr pillows his head on it; she moves slightly away; he follows and puts his head down again; etc. Behr and Damiano Ottavio Bigi lie side by side on their backs, and Morena Nascimento reclines across them, smiling smugly as they strain to do partial sit-ups.

At one point, Behr approaches Anna Wehsarg as she sits primly on a chair and carefully pours water onto her head; she, unperturbed by the ongoing drenching—opens a small purse so she can fix her makeup and comb her hair. (The terrific Behr spends a lot of his time racing around, bringing a restaurant table, attaching a climbing rope across an invisible chasm, and cleaning up after others.)

In one lively scene, Suels Mendoza sits expectantly in a chair, while one woman after another approaches him. He greets each effusively with words and kisses. “Wow!” he cries. And “guapa!” He welcomes Jasjfi as “la pequeñita” and tells Seyama that white becomes her. It’s finally the tallest— red-gowned Clémentine Deluy—who escorts him away. Deluy also takes part in a typical Bausch gambit—that of contacting an audience member with something more than a flirtatious smile or a question or a boast (“I’m fabulous”). She requests a front-row spectator’s spectacles, cleans them off on her gown, and hands them back.

There’s are sequences of gender playtime/warfare. Men toss peanuts, and women try to catch them in their skirts. The guys also spit them out from handfuls they’ve stored up. The classical repertory gets skewered when Seyama keeps approaching Suels Mendoza with a variety of familiar phrases from famous ballets, ending each one by kissing him before she backs up to try another excerpt.

Near the beginning and again near the end of the piece, Behr and Silvia Farias Heredia lie head to head, holding hands; others drag them apart. When Mercy is dancing with Deluy as if in a ballroom, he slips down gradually, until his head is pillowed on her chest. Forces that lovers can’t combat may separate them, and that may be one of the piece’s understated themes. However, the pose that ends . . .como un moguito. . . is not, I imagine, one that Bausch would have chosen had she anticipated her death. The piece begins with Farias Heredia on all fours. Men rush on, pick her up without disturbing her position, and set her down in a new spot. And in the final rewind, that’s how she is left when the lights go out—alone and very, very vulnerable.

Dear Deborah, As always it is a pleasure reading your work!

Your vivid images re-staged Pina’s show emotionally in my mind! A big hug, Anabella.