Dance doesn’t happen in a vacuum. One evening, I’m at the Baryshnikov Arts Center’s Howard Gilman Space—glancing from time to time at the night city glowing outside two big windows, listening to some rich recorded music, and watching a delicately intense, sometimes barely moving dance by two people that traverses two hours without intermission. The next night I’m in another theater named after the same generous patron, BAM’s Howard Gilman Opera House. This time, the music is loud and calamitous, the dancing ferociously, exhaustingly physical. The piece, a spectacle lasting about 70 minutes, is bursting with action yet depicts a society in stasis.

I’m talking about Raimund Hoghe’s Pas de Deux (co-presented by the French Insitutute Alliance Française and choreographed, in part, during a residency at BAC) and Hofesh Shechter’s Political Mother. The two are twanging together in my brain, their differences thrown into relief by proximity. Would the music for Political Mother have seemed less abrasive had I not been listening to Bach, Mahler, Gershwin, Fred Astaire, and others the evening before? Does Pas de Deux seem, in memory, gentler than it was because of the fiercer choreography the following night?

Pas de deux: a stroll for two. Also a ballet delicacy for aficionados of virtuosity. Hoghe opts for the former but alludes slyly to the latter from time to time. Like any pas de deux, his duet is a study in differences and similarities, an interplay of powers. Hoghe is a small man—not young, not old. He has a crooked spine. It’s interesting that performing (he is also a writer of consequence) has changed his body over time. His posture seems straighter, his hump less noticeable than it was when I first saw his work. He often juxtaposes himself to younger performers. His partner in Pas de Deux is Takashi Ueno, a slender Japanese dancer in his early thirties with a limber body and ease in moving it. The men have cultural differences too (Hoghe is German). How they signify these differences—watchfully, tenderly, questioningly, playfully—is moving and enlightening.

The music is a crucial part of the piece, rendering the simplest moves more complex. A soprano aria from Mozart’s Cantata Grabmusik, K.42, is heard in the distance when Ueno enters from behind the audience and walks toward the back of the big studio theater. He walks slowly and carefully, partly because he’s wearing geta— those traditional Japanese sandals that elevate the wearer by means of two parallel slabs of wood—and partly because he is dribbling liquid from a long-handled cup down his left arm. As he passes the sidelights, his fingertips glint like diamonds, and he leaves a trail of drops that don’t seem ever to dry. Hoghe enters a little later, from the opposite side, also wearing geta (these must be muted in some way; they don’t clack as they usually do). He’s carrying a parasol. As the two men meet at the back of the performing area, you think about the little waterfall meeting the umbrella. But it doesn’t.

The performers in Pas de Deux rarely touch, although a couple of times they hold hands or nestle their temporarily shirtless backs together. Ueno lifts Hoghe several times in somewhat awkward and unbeautiful ways (a token nod to the ballet pas de deux form). More often they act upon each other mediated by fabric or air. They enwrap themselves in sashes like Japanese obi and use them to bind themselves together. Each in turn lifts his partner’s arms by picking up his shirt at the elbow or making him rise on tiptoe by lifting his collar (Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, swelling and rippling with its tremendous fervor, plays against the quietness of the act). Circling the room, the two keep running to meet in the center with a little hop; they raise their right hands as if to clap them together in a folk-dancey high five, but don’t make the contact.

There’s a humorous aspect to this relationship. Smiling, Ueno runs and leaps around and around a circle, occasionally stopping and looking questioningly at Hoghe, who stands at the center—affable, but making small, brusque gestures to indicate that Ueno should keep going. Once, Ueno wraps a wide sash around his waist, ties it, then steps out of it. Hoghe picks it up, puts in on his head, and strolls about, flourishing a tiny but long-stemmed flower as if it were a cigarette holder. This while Audrey Hepburn is singing “Moon River,” followed by Judy Garland with “I Love Paris.”

Some of the simplest scenes burgeon with possible meanings. When they stand close together, Ueno slightly behind Hoghe, and each moves one arm in an individual fluid pattern, I imagine at first that they’re writing something on air; if so, it’s the same words over and over. Those sensitive, many-times repeated gestures have the tendrilly look of plants.That image resonates much later when there is talk of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and a woman’s soft voice says that for a chemical reason, on the twentieth day after the explosion, plants began to flourish and flowers bloomed, even as people died from the radiation (shortly after we hear the terrible explosions, a passage from Mahler’s “Resurrection” symphony seems both to question and soothe).

The references to those devastating bombings enter the quiet sparring as a shock. It’s unnerving at first (too tremendous an event to be domesticated in art). But the end of World War II is as much a part of Ueno’s history as are the sashes and the sandals—items of clothing that, by the way, aren’t used just as cultural artifacts. When each of the performers holds a long piece of cloth (a potential obi) by one end, he draws it gently along in such a way that one man’s strip of fabric slides over the other man’s like a caress. Ueno dances with an uncannily lyrical slipperiness; when he does so while wearing the geta, he can slant forward, braced by the tipped sandal. Hoghe, who was born in Wuppertal and served as Pina Bausch’s dramaturge for ten years, has a German dance heritage to display, which he does, in part, by walking around, holding up to the audience an iPad bearing a long-ago film of a woman dancing; it’s Gret Palucca, one of the important figures in 1920s and 1930s German modern dance, whose school was closed by the Nazis because she was Jewish.

Hoghe and Ueno are both wonderfully sensitive performers, masters of the nuances of gesture. But their differences are fascinating too. Ueno is without any unnecessary tension. Sometimes he’s so deep in thinking and feeling the music that he’s almost somnambulistic. Hoghe is as alert as a bird, waiting, watchful, charged in his stillnesses.

It isn’t easy to sit in a not-too-comfortable theater seat for two hours watching a work this spare and low-keyed, and now and then a few people leave. On Wednesday, October 10th, late in the performance, one major figure in American dance education, now frail and in her 90th year, exited the theater with such small, steady, contained steps that she seemed, for a few moments, to be paying homage rather than walking out.

Hofesh Schechter’s Political Mother begins with a ritual death and ends with an artificial rebirth. A dimly spotlit man (Chien-Ming Chang) in samurai attire commits seppuku in a thoroughly grisly manner. It takes him several agonized seconds to die after he has managed to push the sword all the way through his body. The final moments of the piece rewind its action (in abbreviated form) back to the beginning. Chang is just rising as the curtain falls.

Interpret this image as you will. A society decrees codes of behavior that must be followed? Schechter— born and raised in Israel, now resident in Great Britain—damn near killed himself making this, his first evening-length work, but rises to the next challenge?

What he created in the 2010 Political Mother is a spectacle built on the theme of oppression, and in the world of this piece, every inhabitant is either in a state of agitation that comes close to being out of control, or is stumbling around anesthetized. Many of Lee Curran’s brilliant lighting effects resemble searchlights—whether designed to seek out rebels, gaudy-up a rock concert, or to call attention to an event such as a Hollywood premiere.

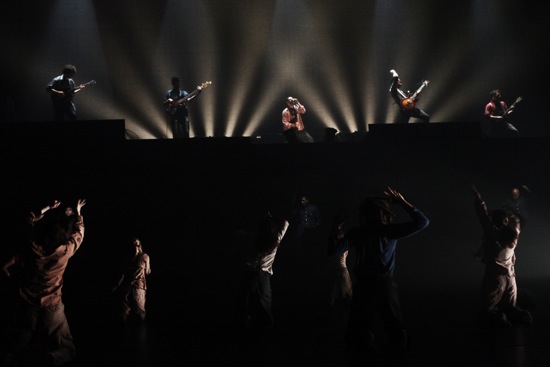

Except for a few gentle snatches of music (a bit of Bach, Joni Mitchell singing about how she looks at clouds from both sides now), the score, by Schechter, is assaultive. Schechter trained as a dancer and a musician (piano and percussion). He played in a rock band as well as performing with Israel’s Batsheva Dance Company. His voice can be heard, submerged the electronic chaos of stringed instruments, beneath with the ferocious sounds made by the band members who appear intermittently in individual pyramids of light on two levels at the back of the stage—four guitarists high up and three drummers beneath them. Additionally, dancer Bruno Karim Guilloré sometimes stands between the guitarists moaning or growling unintelligible words into a microphone—an unholy combination of a lead singer, a dictator, and an animal howling its frustration (I think it’s he who at one point inspects the troops, so to speak, wearing a gorilla head).

In this ambience of glare amid darkness, twelve dancers struggle, freak out, give up, collapse, stand up and do it some more. Sometimes they could be drilling; at other times shambling versions of Israeli folk-dance steps appear. Many, many times, they stand (or dance) with both their arms overhead—most often loosely so, not stretching up. They could be rejoicing, surrendering, or hanging from ropes, but their very numbness makes any fixed interpretation inadvisable. Sometimes they wear everyday clothes; at other times, they’re in what could be prison fatigues.

For all the energy emanating from the stage, Political Mother’s predominant vision is of a defeated society. How is it that these people can be both apathetic and violent? Perhaps it’s because they often don’t seem to will the violence; it takes over their bodies. In one extraordinary bit, Philip Hulford seems to be pleading for something, shaking all the while; then he catapults himself into a back flip. Order and chaos mate. Gathered together, the performers all go crazy in private ways, then in unison, then again shuddering and flailing in the Dante-esque snakepit.

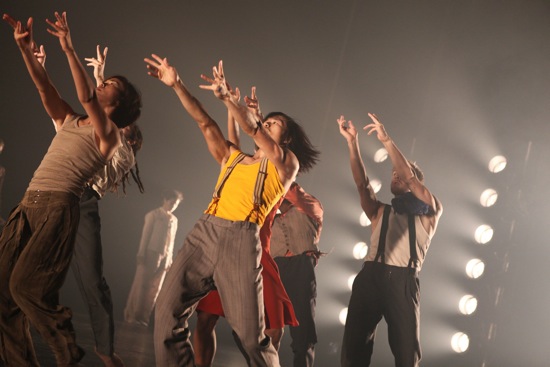

Yeiji Kim (foreground), Maëva Berthelot (red dress), and others in Political Mother. Photo Julieta Cervantes

Schechter organizes everything skillfully. There are moments of semi-calm. People form trios, organize into squads. Tenderness is rare, and a small duet for Hannah Shepherd and Sam Coren ends with his crawling on his belly to reach for her ankle as she backs away. Several people sit and watch one man (Guilloré, I believe) dance a slippery complex solo in place, as if he were evading the air.

Political Mother is tremendously exciting at the outset—the volume of sound, the ominous lighting, the powerful dancers. You feel jolted in your seat. Strangely, though, the piece’s impact diminishes for me as it moves along. Or doesn’t. There’s so much activity of the same sort that you seem to be looking at fragments wheeling around in a shaken glass, never poured out. I felt that way about two dances of Schechter’s, Uprising and In Your Rooms, which I saw in 2008 at Jacob’s Pillow. But the feeling is intensified with Political Mother because it’s such a large-scale spectacle and gets your pulses pounding almost from the minute the curtain goes up.

People in the audience giggle when, near the end of the work, the sentence gradually writing itself on the darkness turns out to say, “Where there is pressure there is folk dance.” Weird, but not so funny when you think about the Middle East. Schechter is making a statement about the world today, as he sees it. We oppress, we are oppressed. We attack, we are attacked. Whether we follow orders or make a stand against them, we’re fucked.

Does anything have any impact anymore?