Chanel DaSilva eyes Travis Walker in Trey McIntyre’s Ladies and Gentlemen. Photo: Taylor Crichton, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow

When Trey McIntyre Project unveiled its new Ladies and Gentlemen in Jacob’s Pillow’s Ted Shawn Theater (August 8-12), you could feel a sunny haze of nostalgia settle over the audience. I’m betting that a good percentage of the spectators could have raised their voices along with the recorded score—songs from the epochal 1972 album Free to Be. . .You and Me, instigated by Marlo Thomas. Maybe—as parents strong on feminism—they’d played it for their kids (the proceeds from the LP went to the new organization that Gloria Steinem, Patricia Carbine, Letty Cottin Pogrobin, and Thomas were building: the Ms. Foundation for Women). Maybe some of them in the audience were those onetime kids, glad to know that a boy could play with a doll or a girl bait a fish hook.

You could have read the book or watched the ensuing tv show. Or you might have been turned off by some of the whimsy and the occasional soft-pedaling (five-year-old William could have a doll, but luckily he was also good at basketball). Most of us stifled any reservations for the greater good. I bought my son a doll.

TMP’s Pillow program was mostly kid-friendly. A deeply touching combative duet was bookended by Leatherwing Bat (2008), set mainly to songs sung by Peter, Paul, and Mary that included “Puff the Magic Dragon,” and Ladies and Gentlemen. McIntyre is some kind of magician and/or an inspired entrepreneur. And I don’t mean that’s just because in 2008 he established in Boise, Idaho a company whose performances can fill the city’s 3000-seat theater—a company that has raised the artistic profile of Boise and brought money into the community. Or because, this past May and June, TMP went on a tour of four Asian countries sponsored by the U.S. State Department and the Brooklyn Academy of Music and recently moved into spacious new quarters in its hometown.

Brett Perry being swallowed by a boa constrictor in Trey McIntyre’s Leatherwing Bat. Photo: Christopher Duggan

There’s also something magical about the way McIntyre approaches the subjects of these two dances—leaching away some of their potential cuteness and conveying darker or more layered subtexts, without losing the polished athletic elements or surface shimmer that draw in large audiences. He does this in part by not pasting obvious pantomime onto the words of each song. For instance, Tom Paxton’s “Going to the Zoo” in Leatherwing Bat depicts specific animals, but you get only a hint of them from McIntyre. Paxton sings of the monkey’s “scritch scritch scratchin;” McIntyre has Ashley Werhun bounce down into a simian squat for a couple of seconds while hanging onto one hand of someone standing. Your eye registers the action, but it’s just part of the choreographic flow. “Puff the Magic Dragon” is a duet for tall John Michael Schert and smaller Brett Perry, who had channeled a child in one of the previous songs. The two dancers could also simply be seen as companions, enjoying dancing side by side or for each other; in the end, Schert simply spreads his arms wide and backs gravely away from us into darkness.

McIntyre’s choreography has the air of fluent conversation or soliloquy. It looks a little like unbuttoned ballet mixed with small everyday gestures (like a shrug or a flick of a foot) and more easy-going contemporary steps—turned in, turned out, fluid, jerky, rounded, angular. He’s extremely skilled at something many choreographers ignore—the intermingling of big, whole-body movements with isolated ones by just an arm, a leg, a head.

It’s also true that McIntyre, who used to make you notice the trickiness or weirdness in his style (say, in his 2004 Pretty Good Year for American Ballet Theatre), now downplays that. Too, the performers (six of the ten came to Jacob’s Pillow) have a way of phrasing that makes everything seem organic. When Schert, also the company’s executive director, investigates the steps of his opening solo in Leatherwing Bat, you notice, of course, how beautifully he wields his long legs, how softly he descends from a leap, but you’re more attracted to the interplay of power and silkiness and the imaginative variegations in texture. Ladies and Gentlemen is as full of rich dancing as it is of revealing moments.

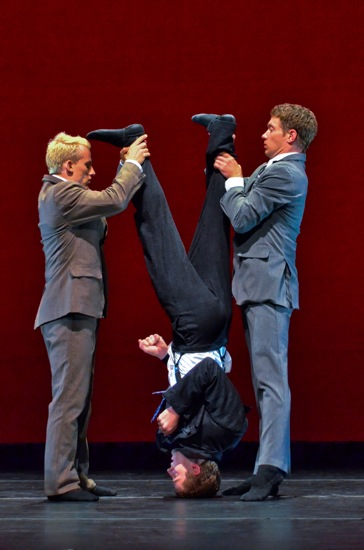

Ryan Redmond and Travis Walker upend Benjamin Behrends in McIntyre’s Ladies and Gentlemen. Photo: Taylor Crichton, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow

The three men wear tight-fitting suits in which they fidget, a bit like boys in new long pants or uptight executives (costume by Andrea Lauer). The women’s short party dresses swirl and swish. You sense an ongoing undercurrent of male bullying and people watching one another as if suspicious of, or puzzled by, what they think of as aberrant behavior. There’s no “doll” for William to want in the song recorded by Thomas and Alan Alda, unless you count the moment in the ensuing ballroom dance to “Girl Land” (sung by Jack Cassidy and Shirley Jones), when women are suddenly lifted as stiff as Barbies.

However, all through the recitation of “My Dog Is a Plumber,” (quizzically spoken by Alan Cumming, instead of the original Dick Cavett), Werhun simply dances, showing us her power and her versatility. In “Glad to Have a Friend Like You,” she and Benjamin Behrends dance-chat with few specific references to the forget-gender activities described in the song (delivered by Kimya Dawson); they’re just enjoying the rough-and-tumble exchanges of their camaraderie.

The through-line of discomfort to do with growing up that McIntyre delineates is pulled tight after this last number. Ryan Redmond and Travis Walker, happening upon the duet, keep Behrends from following his pal offstage, but while, in the background, Redmond beats up Behrends in slow motion, Walker dances frantically in what we can assume to be a struggle with himself and ends sitting on the floor, his hands over his face. When the other two go, and Chanel DaSilva, Werhun, and Rachel Sherak enter, he hides his head under Werhun’s dress and crawls upstage with her.

Benjamin Behrends and Ashley Werhun, “Glad to Have a Friend Like You.” Photo: Taylor Crichton, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow

Just before the end, DaSilva sings, a capella, “Free to Be.” Then in “Sisters and Brothers,” the last of the ten numbers, the women gradually strip away their dresses, the men toss them, and in the end everyone’s wearing vivid, multicolored leotards. I can’t help wishing that the women, just once, would hoist the men. But they all appear for their curtain call in a mélange of hastily donned renegade attire—a jacket on a woman, one of the skirts on a guy.

Between Leatherwing Bat and Ladies and Gentlemen, McIntyre gives us Bad Winter (2011), a dose of uncompromising adulthood in two parts. DaSilva, wearing a white tailcoat over skimpier attire, eloquently dances out a struggle to an old recording of a not-so-sweet song: “Every time it rains, it rains pennies from heaven. . .Trade them for a package of sunshine and flowers. If you want the things you love, you must have showers.” She’s like an entertainer trapped in the truth of the song.

The second part involves two people (Walker and guest artist Lauren Edson, a former TMP dancer and a Jacob’s Pillow alum). They are breaking up, with all the regret they feel and all the determination they can muster. It’s a beautiful, intensely sad duet, without conventional virtuosity, set to “That Home” and “To Build a Home” (recorded by the Cinematic Orchestra) and bleakly lit by Travis C. Richardson. The two watch each other. They think. What went wrong? Walker slowly lowers his hand and places it on Edson’s shoulder; she ducks away from it, turns, and swiftly braces herself, as he presses his head against her stomach. Their bodies fit together so well, yet, somehow, not really at all anymore. She pushes her head under his loose blue tee shirt; a few slippery moves later, she’s wearing it, and he’s lying flat on his back. In the end, he’s down again, clutching the shirt. She rolls him over, and it comes free. Gone with the wind.

Bad Winter is a sobering moment before Ladies and Gentlemen takes us back to the 1970s. It’d be nice to see more gender equality being preached to kids of today. There are times when I think I’ll gag if I see one more little girl in pink ruffles bearing a teensy pink backpack, but at least I’m not the only one who hopes she’ll get over it.

“There are time when I think I’ll gag if I see one more little girl in pink ruffles bearing a teensy pink backpack…”

Yes, but that’s not nearly as irritating as the pink sweat pants with “Princess” embroidered on the seat.

That’s what I’d call a mid-third-grade crisis.

Amen, or perhaps awomen to both of you Deborah and Sandi, and thank you Deborah for making me see Trey’s new work through your eyes. I too think he is “some kind of magician” and I know him well enough (he was resident choreographer at Oregon Ballet Theatre; I’ve been following his career for many years and have spent quite a bit of time in Boise, the last time reporting for a cover story for Dance Magazine) to know that everything he does comes not only from his fertile brain but from his heart. And as a footnote, my four year old grandson adores the recording of Free to Be…

McIntyre has also been welcomed as a guest choreographer in recent times and nearby places, like here in New Jersey, to our great glee.