In 1931, Noël Coward walked out of the first public performance of William Walton’s Façade: An Entertainment in 1923, and a critic described the music for flute, clarinet, trumpet, saxophone, cello, and percussion as “relentless cacophony.” Coward may have been put off by the fact that Edith Sitwell, the author of the poems that formed Walton’s libretto, sat behind a screen and read the text into a megaphone that poked through.

Ernest Newman, however, writing in London’s The Sunday Times, said of Walton, “as a musical joker he is a jewel of the first water.” You could say that of Mark Morris, too, and it was a midsummer delight to hear him read Sitwell’s text alongside soprano Lucy Shelton at Tanglewood’s Seiji Ozawa Hall, while members of the Mark Morris Dance Group performed his 2002 Something Lies Beyond the Scene and Fellows of the Tanglewood Music Center expertly played Walton’s score. (The performances took place June 28 and 29.)

Sitwell didn’t want Frederick Ashton to use her poems when he choreographed his Facade; the ballet is performed to the orchestral suite alone. However, as anyone who has read Sitwell’s poems or heard the 1970 recording of Façade by Dame Edith herself, tenor Peter Pears, and the English Opera Ensemble knows how wonderfully eccentric the texts are and how deliciously they are timed with the rambunctious instrumental music. (You can sample that recording online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=j5AlUOJs2dI). The twelve poems that Morris has chosen from the more than forty that Walton eventually set to music require that the readers be able to stretch out words soothingly in, say, “Lullabye for Jumbo” or speak the lines of “Something Lies Beyond the Scene” in 6/8 time (the sixth beat being a pause): “We bear velvet cream,/Green and babyish/Small leaves seem; each stream/Horses’ tails that swish. . .”

Other lyrics like those in “Tango-Pasodoblé” require a precise, top-speed fusillade of words, which Morris recites with gusto. Shelton is especially fine in the caressing passages that hint at summer by the sea in long-ago Le Touquet, or on the Spanish coast, or in an English garden, although I had trouble making out her words at first.

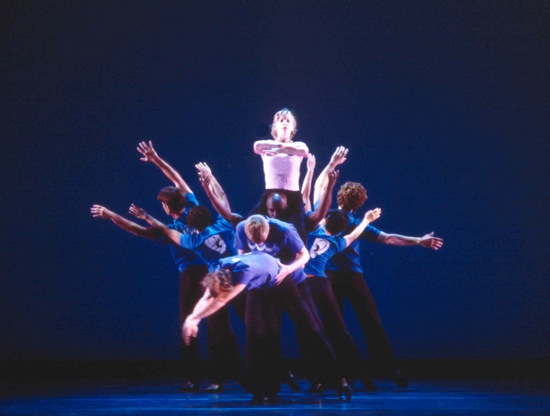

Lauren Grant and MMDG men (an earlier cast of Something Lies Beyond the Scene) in “Lullaby for Jumbo.” Photo: Ken Friedman

The choreography sometimes pounces on the images the words conjure up and sometimes slides only into the mood and rhythms they engender. In “Tango-Pasodoblé,” Noah Vinson peers around the legs of four other performers as if they were the trees mentioned in the poem. In “Lullabye for Jumbo,” seven dancers suggest the body, head, and waving trunk of an elephant while Chelsea Lynn Acree rides it. In the wintry scene depicted in “By The Lake,” Laurel Lynch and William Smith III are a mournful pair, and other couples pass through shivering. There’s also a great deal of boisterous, playful, or tender dancing.

The costumes by Katherine Patterson consist of black pants and T-shirts in various pastel shades. Each of the ten dancers must have a whole set, because they’re always changing colors (in “Jumbo,” for example, all the performers wear blue shirts, while Acree is in a pale pink one). Michael Chybowski’s lighting makes them glow, even on beautiful Ozawa Hall’s rather untraditional stage.

Rock of Ages (2004), like Something Lies Beyond the Scene, premiered at the University of California’s Zellerbach Hall. I’d never seen it either. In the past, it has been performed by two men and two women; at Tanglewood, Rita Donahue, Amber Star Merkens, Maile Okamura, and Michelle Yard were the dancers. They wear short, royal blue skirts and tops, and Nicole Pearce’s lighting gives them a backdrop to match. The piece is set to the Adagio from Franz Schubert’s Piano Trio in E-flat, D.897, excellently played at for the performances in Ozawa Hall by three of the Music Center’s New Fromm Players: Alexander Bernstein (piano), Alex Shiozaki (violin), and Michael Dahlberg (cello)

.The title is something of a mystery, although the heroic, six-note, dotted pattern that guides the “B” section echoes the rhythm of the well-known hymn “Rock of Ages” (and even, at one point the three notes that sigh “cleft for me”). The music, a nocturne, is ravishing, and Morris has captured the hushed, questioning quality of its “A” section beautifully.

In the beginning, the violin and cello play the melody (in thirds, I believe); the piano enters underneath and ripples a modest answer. But after the opening passage is repeated, the piano takes over the melody, while a plucked violin comments sotto voce. Morris has picked out this duality in various ways. Donohue and Okamura make simple, large, contrasting movements close together in the center of the stage, then come forward in unison, ending the passage facing away from the audience, their hands clasped behind their backs, their heads turned to the side, their gazes high. Yard and Merkens have their own slightly different pattern centerstage, as I remember, but repeat the other pair’s unison passage. (Hear the music at www.youtube.com/watch?v=K3M38okVTX8.)

(L to R) Michelle Yard, Rita Donohue, and Julie Worden in an earlier performance of Rock of Ages. Photo: Susana Millman.

The Adagio is slow and sonorous, with hints of darkness. Merkens falls, and the other three don’t immediately notice her. When they do, she lifts her head and legs awkwardly, then rolls to lie supine for a few moments. But this strange little drama isn’t typical of the choreography. Whether the women are thrusting into the more assertive “B” sections— lifting one another, leaping—or responding to the soft statements of the “A,” you feel that they are intent on fitting into a pattern, complementing one that’s already established, answering a question that another has proposed. At the end, they turn and walk offstage one by one, then reappear, gaze at one another and at the place where they’ve danced, then slowly exit at the four separate corners where they began.

The program was clearly chosen to show off the talents of the young Tanglewood Fellows, as well as the company’s marvelously musical dancing. The program closed with Morris’s 2011 Festival Dance, with Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Piano Trio No. 5 in E, Opus 83, played by pianist Ryan MacEvoy McCullough, violinist Micah Ringham, and cellist Dahlberg again. In this ebullient work, we get to see relative newcomers Lesley Garrison and Spencer Ramirez mingle with the more seasoned Morris dancers like those mentioned, plus Samuel Black, Domingo Estrada, Jr., Aaron Loux, Laurel Lynch, Dallas McMurray, and Jenn Weddel.

The piece begins with a couple, Loux and Donohue, exploring how they might perhaps dance together for a lifetime and ends with them embracing. In between, many other couples celebrate, as do threesomes and quartets. The whole community joins in festive chains and circles and abets what might be a wedding between Lynch and Smith.

One fine thing about Ozawa Hall, in addition to its superb architectural design by William Rawn, is the fact that—because the auditorium lacks a curtain, wing space, or a backstage area where the dancers can warm up—the audience willy-nilly sees some of the preliminaries leading up to the performance. The night I attended, dancers, on their own and together, went over and over one sequence so many times that when it occurred in Something Lies Beyond the Scene, it felt like an old friend. Yard and Estrada practiced a flying lift in Festival Dance enough for us to understand how it worked and admire their timing and collegial spirit. It’s always fun to watch preparations that fumble and sprint their way to success and then see the thrilling moment in which they become art.

Lovely Deborah, comme toujours. And how I would love to see Morris’s version of Facade and hear him read the Sitwell poems. I have seen the Ashton version; Christopher Stowell programmed it for Oregon Ballet Theatre in 2004 I think, his first season as artistic director, and I am ever grateful. The company did well with it, I might add.

Thanks again, Deborah, for the excellent report.

I’ve seen Rock of Ages, here in Berkeley — but only once, and once is not enough with Mark Morris — you can barely see his work the first time, or at least I can’t. I remember being moved, but I can not remember details. And thanks for the link to the music. It helps to picture what you’re talking about to hear the music. And now I’m aching to see this dance again

Did you go back to see it with a heterosexual cast? it changes things so much — I remember Remy Charlip made a piece for Oakland Ballet, with maybe 5 couples — each night it was different, one night with M/F couples, one night with M/M, and Sunday with F/F; of course the lifts were different — but all KINDS of things were different. I remember Mario Alonso wore a skirt and that added a whole other dimension to the close-ups [I THINK there was a bit where one dancer passed under and between the other’s legs, but maybe I hallucinated that. It was a bigger deal the night it was ALonzo’s legs.]

And thanks for the following: “The night I attended, dancers, on their own and together, went over and over one sequence so many times that when it occurred in Something Lies Beyond the Scene, it felt like an old friend. Yard and Estrada practiced a flying lift in Festival Dance enough for us to understand how it worked and admire their timing and collegial spirit. It’s always fun to watch preparations that fumble and sprint their way to success and then see the thrilling moment in which they become art.”

So true, and so well-said.

I appreciate your comment very much, Paul. I only saw one performance at Tanglewood, but the cast of “Rock of Ages” didn’t change. Male-female switches in casting, however, aren’t uncommon with Morris. One early piece whose title I can’t recall could be performed either by all men or all women. I also remember that when I asked Clarice Marshall who was understudying Baryshnikov in Morris’s “Wonderland,” she said (with a slight gulp) “me.” And there’s Morris’s own spectacular performance in two female roles in his “Dido and Aeneas” (which is being revived this summer), and the three cross-gender roles in his “The Hard Nut,” not including the dressed-alike male and female Snowflakes. Don’t forget, too, his brilliant notion of casting women as Tybalt and Mercutio in his “Romeo and Juliet, On Motifs from Shakespeare.”

I loved how you drew us in with the beginning saga of Facade and only wondered how is it that Morris COULD use Sitwell’s poems? Apparently from your description it was fabulous. Thinking about all you said really urged me to somehow find out where else it will be performed on the off-chance I too can watch. Your Berkshire area with this performance at Tanglewood and all that goes on at Jacob’s Pillow is so incredibly rich in the summer!

Thank you from reporting from there! Judith

We’re often told that that one of the bonuses of web-based criticism is the ability to link to other ‘stuff’ that might explain or enhance the points we’re trying to make. Many of us are still trying to work out the best ratio of review-to-footnotes — you’ve done a very crisp job of it here.

Thanks so much for the thoughtful discussion of Morris’ new-ish repertory — I wish I saw them more often.