What would it be like to travel around in Trajal Harrell’s squirrelly postmodern brain? Circuits must crisscross, merge, restructure. Destination? Don’t ask. Enjoy the ride. The title of the latest entry in Harrell’s series, Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church is prefaced by Antigone Sr./ and followed by its size: (L). Those who have seen the (XS), (S), (M), and (Jr.) versions will know that the enterprise began with a question that Harrell asked himself in 2009: What kind of work would have ensued had some voguers left the Harlem ballrooms in 1963, taken the A train down to Washington Square, and cozied up to the movers and shakers at Judson Church?

Probably nothing like what the super-smart Harrell has dreamed up. But who cares? While he challenges the audiences at New York Live Arts with prolonged repetitions (Antigone Sr. runs about two and a half hours) that transport some of us back to the dance scene of the sixties and seventies, he also tackles many of the aesthetic issues that Judsonite Yvonne Rainer said no to in her 1963 manifesto. In fact, he seems to be saying no to her manifesto itself and yes to much that she marked to be discarded. Glamor? Check. Narrative? Check. Camp? Check. Yes to style, spectacle, the heroic, and “moving or being moved.” But, of course, Harrell embraces none of these taboos as they were defined by obstreperous young choreographers of the early 1960s intent on breaking away from, say, Martha Graham.

If you try to deconstruct the title of his serial works, ambiguity becomes your lodestar. “Looks” (are there always 20?) as in gazes and in styles (the “I’m-15-and-already-dead” look of some fashion models today). “Burning” as in destruction of a city and the look of a really hot runway show. And, unstated in the title, but raised during the show: House Dance, the House of Thebes, the House of Chanel. Fascinated by the transformative aspect of clothing, Harrell identifies the dances by dress size.

The fashion parade is tied, snapped, and hooked onto Sophocles’ tragedy of Antigone, daughter of the incestuous mating of Jocasta and Oedipus. By the end of it, five principal characters are dead. Antigone’s brothers, Eteocles, and Polynices have killed each other other over the leadership of Thebes. Antigone has hanged herself after Creon, her uncle (now king) ordered her walled up. His son, Haemon, Antigone’s fiancé, has committed suicide, and so, for different reasons, has his wife, Eurydice (no, not that Eurydice). Antigone’s sister, Ismene, asked to be killed with her sister, but Creon refused. Perhaps more important to Harrell than this dismal body count were Creon’s unfairness and injustice (he blamed Polynices—but not Eteocles—for the strife, and forbade anyone to mourn him or give him a proper burial) set against Antigone’s courage in defying him.

Harrell and his all-male cast, don’t, however, “play” characters, enact their encounters, or project their emotions in traditional ways. Instead, as in the 1960s, symbolic acts, descriptive words, and here-and-now remarks jostle against one another to ignite images grounded in the ancient drama and ideas about art.

The House of Harrell is a handsome space. Black curtains hang at the back of NYLA’s stage, with gaps through which you can from time to time glimpse the performers changing outfits (additional apparel and towels occupy aisle seats). Erik Flatmo’s set consists of three white rectangles and a slightly higher, draped platform, bristling with microphones; a mesh of color-edged runways; and an upstage object that looks like a giant fluted vase. Jan Maerten’s lighting makes the stage and its performers look very beautiful and, when necessary, moody.

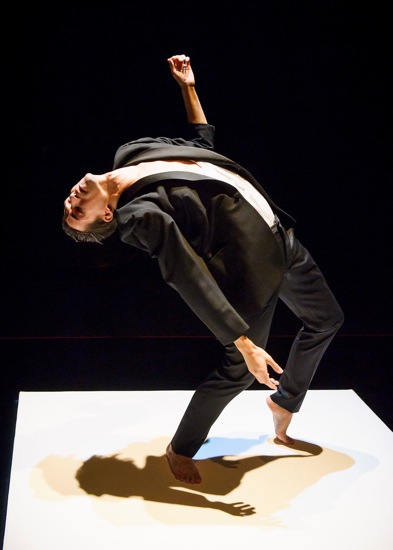

Oh, those performers! All men. All except for Harrell and Ondrej Vidlar fashion-model reedy. All, except for Harrell, white. All of them trailing impressive international reputations. All, with no exceptions, adept at sashaying down a runway or onto a dance floor. All terrific. Harrell introduces them to us as dancers; wearing trendy black, each in turn takes the spotlight on one of the white rectangles. You can relish the contrast between Vidlar—a powerful performer whose muscular flexibility makes him look like a fighter punching and evading several opponents–and Stephen Thompson. Thompson, in an equally three-dimensional display, and dancing to the gentle, lazy voice of a female singer, twists and bends as if under a hot shower. Thibault Lac, tall and slender, flips his long legs around more than the other two, and Rob Fordeyn is more active still. The sound design, by Robin Meier and Harrell, provides a pounding beat when necessary, glides into relevant pop music, dredges up layered whispers, and strikes chords and melodies that sing and whine under the drama.

Harrell brings the men’s exhibition to a halt by yelling “Stop the beat! Stop the motherfucking beat!” And though he dances later, with bold-face, dug-in vigor, he’s the main MC, the rapper, the storyteller and also, I think, Ismene. For a long time, he and Lac sit on the draped platform (by now, all but Harrell wear white draped tunics.) At first, the two trace fluid patterns on the air with their arms, then recite together and separately the names of well-known pairs. Each entry —Mary Kate and Ashley, Beyoncé and Solange, Venus and Serena— is preceded by a drawled-out “We are. . . .” They “are” also Simon and Garfunkel, Bombay and Mumbai, Deleuze and Guattari, and, finally, Antigone and Ismene. Sometimes in this long, long litany, they almost seem to be free-associating; when one says Sense and Sensibility, it’s not hard to guess that Pride and Prejudice will follow.

Elements of the Greek tragedy emerge fitfully, most obviously in words, although two of the men do wrangle in the background (could be any of the Theban antagonists). After we hear, “my sister’s gonna die,” Harrell looks about to weep. A line from one of The Middle East’s songs seeps in: “And it’s the darkest side of my heart that dies when you come to me.” Lac stretches cords between members of the audience and Harrell, who pins them down with one hand. Could they represent the web Eurydice weaves in Sophocles’ play? Later, Fordeyn reappears in a little black dress and very high heels, and he and Harrell sing together a woeful song that reprises “we are” and adds “you are” and “I am”—as in “I am safe from life. I am already dead.”

It’s startling how Harrell (aided by dramaturge Gérard Mayen) pokes plot elements through a runway show the way the men insert themselves into costumes and more costumes. Gossip and mild bitchery beset this “house” while death and passion slide in like shears cutting silk. Lac sashays around in a tunic of two large scarves tied together, Harrell calls out, “It’s not about the scarf, it’s about the briefs underneath;” Lac smiles sweetly, steps out of the briefs, and exits.

The fantastic costumes concocted by Harrell and the performers draw from the same backstage pool. After a while you begin to see how one person’s wig becomes another’s sporran, how a jacket turned inside out gives someone superman shoulders. You can track that piece of red fabric, or that gold thing that starts out like a breastplate, through several reincarnations. As the bedecked men model them for us, their bare feet sometimes clad in imaginary high heels, the bizarre combinations occasionally strike a darker note. When Harrell is alone, holding the white cords, Thompson advances bare-chested, with a black leather coat buttoned around him into a sarong, his hands gloved in its sleeves; a white fringe conceals his face.

When I look at the last page of my scrawled notes, I can tell that Antigone Sr. did somehow build and become more intense, as if its postmodern cool were fraying. The jokes (“Jill Sander is back in the House” when Lac strolls in in a little black dress) fade out, and the cross-cultural mash-ups turn nasty (Harrell dancing and grunting, “I’m gonna take that bitch to college, gonna get that bitch some knowledge”). We hear phrases such as “The roof is on fire,” such as “The Fates are coming for Creon,” such as “Are you ready?” Vidler dances a long solo (marvelously) while the others change into white clothes (Lac in the aisle beside me).

Antigone Sr./Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church (L) sometimes seems overburdened by its mass of material. It is also crystal-clear and enigmatic, hot and cool, boring and engrossing, exaggerated and matter-of-fact, a tragedy and a comedy, confusing and carefully structured. A motley collection and a modest triumph.

Thanks Deborah, for adding me to your list of e-mail Blog recipients. I’ve always enjoyed your writing, and now will be able to continue to do so very conveniently.

Best wishes,

Miriam

Is Harrell meant to represent Tiresias in Thebes? Harrell’s (upper) body has a transgendered look.

Caption of the final photo: who is Stephen Douglas, please?

It’s hard to know. Tiresias was mentioned. Transgendered? Maybe a trick of the lighting. . .

“Stephen Douglas” is Stephen Thompson. The photo caption has been corrected. I didn’t need to bring Civil War politics into an already heady mixture.