Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet is the most stable mid-sized company in New York. Its top-notch funding guarantees that its dancers are very well taken care of, which means that they don’t come and go. Every time artistic director Benoit-Swan Pouffer puts together a new program for a season at the company’s own black-box theater on West 26th street or at the Joyce Theater (this spring, May 15 through 27), I look forward to seeing the dancers in new guises.

They’re virtuosos, but more importantly, they seem to approach each work with fervent commitment. If a choreographer asks them to sing, they sing. If speaking is wanted, they speak. Can they tie themselves into knots without falling over? Sure. Are they willing to rebuild their bodies and psyches temporarily? Improvise with props? Oh yes! They give the impression of loving the challenge of transforming themselves.

Five of the six works divided at the Joyce into two programs were created for Cedar Lake, and all featured the kind of edgy international choreographers who interest Pouffer. Program B (the only one I was able to see) consisted of pieces by Regina van Berkel (Holland), Alexander Ekman (Sweden), and Jo Strømgren (Norway). For van Berkel’s Simply Marvel, the dancers oiled themselves into sinuously complex movements that testified to the seven years the choreographer spent dancing with William Forsythe’s Ballett Frankfurt. To comply with Ekman’s plan for Tuplet, they talked and slapped out complicated rhythms on their own bodies. Strømgren’s Necessity had them hurling sheets of paper around. They were never less than marvelous. My only regret was that all three works were double cast, and several company dancers didn’t appear at all the night I went.

Theo Verby composed some of the music for Simply Marvel, but most of it is Niccolò Pagannini’s excruciatingly difficult variations on Giovanni Paisiello’s aria “Nel cor più non mi sento” (recorded by violinist Viktoria Mullova). At times, you can imagine a hive of bees on the rampage, and, yes, you do marvel, and, yes, to parse the title of the original aria, everyone on stage seems solitary much of the time—not feeling much in their hearts but fiendishly trying out challenges to their bodies.

Beneath the white paper curls of Dietmar Janeck’s set, the initial vision is one of isolation. Soojin Choi and Matthew Rich form elegantly kinky tangles in a small patch of space upstage right (she’s on pointe and occasionally shoots out an arabesque; they wear matching yellow tops and brocade diapers designed by the choreographer). Some distance away in the upstage gloom, Jubal Battisti stands for a long time with his back to the audience, while downstage —lit handsomely by Dieter Janeck and accompanied by single piano notes—Oscar Ramos dances a long solo. The movement is both bold and evasive; Ramos looks as if he’s trying to shrug his way into a garment of air that keeps dodging around him. Ebony Williams Joins, Acacia Schachte and Joaquin de Santana make a statuesque appearance, Jon Bond creeps in from a downstage corner.

The first part of Simply Marvel unreels in a darkish tone—with Ramos and Battisti scrimmaging briefly, Choi breaking free of de Santana’s embrace, and the men clustering in a traveling snake pit of limbs. But, eventually, as the dancers move into three identical trios or pair up, they get happy.

In van Berkel’s choreograpy, every potentially simple move is decorated. A dancer seemingly can’t reach out a hand without undulating a shoulder, rolling the head, maybe canting the ribcage a little. This density of motion is the main connection of the choreography to the music; Paganini doesn’t provide structure or style, but he certainly doles out itch. The 18th-century aria that inspired him and a number of other composers opens with the soulful line, “My heart no longer feels the fire of youth.” Tell that to the Cedar Lake dancers!

Ekman’s Tuplet begins informally while the audience is returning from the first intermission. As the stagehands prepare the scene, Harumi Terayama stands on one of the rows of white squares laid downstage and vigorously punches out a rhythm with her arms; maybe she’s shaking invisible maraccas. A recorded voice da-da-ing can be heard dimly and, later, vocal sounds like the rhythmic syllables that accompany Indian dance (the score is by Mikael Karlsson). Two screens display close-up images of the dancers’ busy mouths and their hands beating on their bellies.

In one of the most winning parts of the piece, the dancers—wearing trim navy blue outfits by Nancy Haeyung Bae— line up on the white squares and hit poses separated by blackouts. At some point, each says her or his name and spits out a gesture to go with it. As the lights pick out one of the six dancers, then another, the effect is of jolts of electricity. Several times in a row, Bond ejaculates his name while twisting his head back twice as if being cross-punched in the jaw (he times his jerky motion exquisitely, and the audience laughs—partly at the connection between his name and Ian Fleming’s hero-spy). The pattern of lights, moves, and sounds escalates.

Rearrangements of the floor panels, more videos, and the sweeter music of Victor Feldman’s piano rendition of “Fly Me To The Moon” finally yield to a virtuosic display by the dancers in their separate lights (design by Amith A. Chandrashaker). Whispering, clapping, and slapping parts of their bodies in exact unison, they build their own kind of fascinatin’ rhythm.

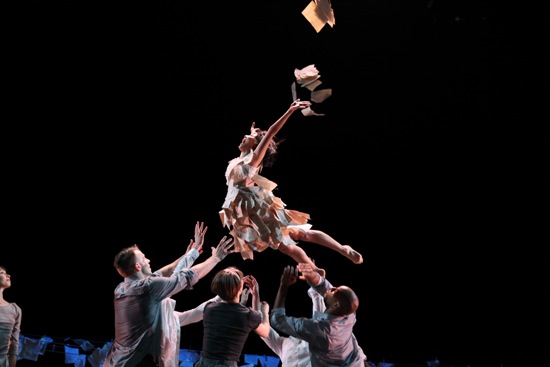

(L to R): Jubal Battisti, Acacia Schachte, and Matthew Rich in Jo Strømgren's Necessity, Again. Photo: Juiieta Cervantes

Necessity, Again (a world premiere) marks perhaps the first—and very welcome—time that Jacques Derrida has been used as a fall guy. Strømgren doesn’t employ spoken snatches of Derrida’s text on necessity in order to educate us, as much as to juxtapose its intellectualism to irrational, breakout behavior. Breakout, in this case, doesn’t mean violence, but wild childlike play, monitored by a selection of songs by Charles Aznavour (additional music by Bergmand Slaslien). The dancers wear office attire by Junghyun Georgia Lee (de Santana even sports spectacles), but this is an office already in the process of running amok when the curtain goes up. While Williams sits at a table looking exhausted (which she does almost throughout), Rich comes in and scatters an armload of papers, and Vânia Doutel Vaz follows up with more.

While Ana-Maria Lucaciu counters a new song with strident moves, others in the ten-person cast are busy in the background with an array of clotheslines that two dancers initially dragged in and hooked up. The lines hold more pieces of paper—the fruits of intellect hung out to dry. These are constantly being taken down or clothes-pinned up. You can imagine Strømgren turning the Cedar Lake dancers loose to see what ideas they might come up with as the atmosphere gets crazier. In this wacky office party, Kittelberger drinks from a champagne glass and sprays it into the air; he turns sheets of paper into earrings. People occasionally join together briefly in cheerfully clichéd musical-comedy routines. Williams juggles ping-pong balls. Rich contracts his body as if he can’t control it; once he’s been laid out, Kittelberger tries to stop the motion by pressing down on his pelvis.

There’s one strangely disturbing vignette. The table is moved to the center of the stage, and Lucaciu lies on it, her head toward the audience, and her bent legs spread. The image of a gynecologist’s examination (or childbirth) is inescapable. Kittelberger, now shirtless, emerges from behind the clotheslines, flipping them out of the way, and advances on her. Everyone gathers to watch; the other men have taken their shirts off too. Do I hear Aznavour’s “Ave Maria?” Nothing drastic happens, and eventually she is peeled off the table. I’m not sure what Strømgren was thinking.

By the end, everyone has stripped to underwear and re-dressed. More and more sheets of paper have stormed the stage. Terayama has reappeared in a dress made of papers, and the others have elevated her like a goddess and lain down so she can walk over them. As the curtain slowly descends, a game of jump rope is beginning with the swinging clotheslines.

Necessity, Again isn’t as powerful as the two earlier Strømgren pieces that I’ve seen, but it’s completely engrossing to watch the gung-ho Cedar Lakers enter so boldly into its hedonistic extravagances.

I luv u guys,you peeople are great,nice concept,wish i can fly and meet you guys,i really love contemporary ballet dance,am an african(Nigeria).cheeeeee…………..ssssssssssssss