I don’t know whether Ivy Baldwin roams around looking for images that will nourish her choreographic appetite, or whether she simply goes about her life and things suddenly catch her eye. Her new Ambient Cowboy was clearly fed by sources very unlike those that produced her Here Rests Peggy (as in Peggy Guggenheim, the deceased art patron).

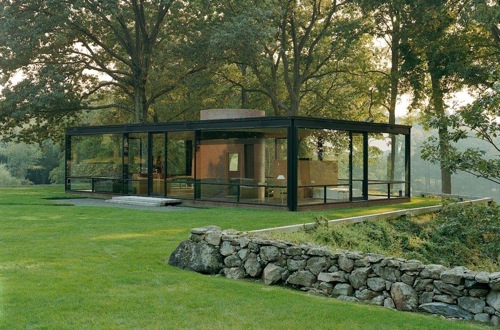

Baldwin has let it be known that Ambient Cowboy began to form in her mind when she visited Philip Johnson’s famous Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut. Johnson’s see-through box is furnished with deluxe austerity: a couple of Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chairs, a matching daybed, and a few other pieces with simple lines. Outside: acres and acres of mowed grass surrounded by woods. Like that paragon of modernism, the dance that Baldwin premiered at New York Live Arts (May 3 through 5) is spare and lucid in its architecture. It could be said to have a certain transparency.

The dancers (Lawrence Casella, Molly Poerstel-Taylor, Eleanor Smith, and Baldwin wear black trunks and semi-sheer, blousy, sleeveless tops, split up the back or front. Sometimes the four sit or stand— steady of gaze and as motionless as furniture. Sometimes they cluster to form architectural designs. But within this containment, there’s something wilder going on, and Justin Jones’s sensitive intermittent score brings this out.

Artist Anna Schuleit’s visual design is both magical and unnerving. At the beginning, a moving line of light draws shapes on the back wall of the stage. It could be tracing a series of low buildings, except that the ends of some of the lines crawl along the floor. Later, when Smith collapses and lies on her belly for some time, the virtual pen furiously scribbles lines back and forth across her prostrate form, netting her in light. When the excellent lighting designer Chloë Z. Brown alters the greenish ambiance, the lines evaporate. I believe that, via some system I don’t understand, Schuleit (unseen) creates these during the performance in response to energies sensed in the dance.

However scrawling and apparently unruly those visions, they appear sparingly in Ambient Cowboy. In the same way, moments in the choreography that hint at emotion or drama do so in controlled ways. For instance, as the piece begins, Casella and Baldwin are standing at some distance from each other. She remains motionless while he begins to pant rapidly and noisily. He does this for a long time, one hand at his chest. It’s painful to watch, but he shows no signs of distress. The dancers also occasionally freeze in tableaux, divorced from whatever caused or preceded the moment. In one pose, Smith sits on Casella’s bent-over back staring into the distance, like a lady riding sidesaddle.

That mysterious cowboy of the title circles the manicured lawn of the dance, and I get glimpses of him—not, of course, as a character, but as a design principle. I can’t help sensing his influence. The dancers run with precise feet, and I think of horses trotting. They leap and I imagine a steeplechase. He’s there in a hip-swinging walk, there when Casella stands flanked by Baldwin and Smith, a stretched-out arm on each of their shoulders. Am I seeing things or did the cowpoke hero just push the saloon’s swinging doors aside?

Whether the dancers wrench and jerk around, or balance on one leg to turn the other into a slow probe—front, then back, the interplay between the cool-toned choreography and the movements that bear elusive significance is intriguing. A dancer puts her hand against her brow. Despair? Wiping sweat away? But when the gesture is a frequently seen motif, matter-of-factly executed by everyone, it loses its potential drama. So does a move in which the dancers shoot their arms up like antlers and then, shaking them as they dance, slowly lower them.

Ambient Cowboy has subtle dynamic shifts, and the choreography builds new, airy structures as the performers come and go. The piece is as elegant in its way as Johnson’s house, which changes as you walk around it. But, like the house, it maintains a certain sameness. If you close your eyes for a while and then open them again, nothing seems to have changed very much. Here they are, over and over: the clean, handsome, forthright shapes fringed with intimations of wildness.

Gradually, one by one, the dancers exit, leaving Poerstel-Taylor to perform an arresting and solo that wraps up many of the previous movement themes. She’s as strong and alert as a deer. Then she takes off running, leaps into the air, and disappears into the woods. . . I mean the wings.

Fascinating form. In that middle pic – is that an effect of the shadows or has she been splattered with something?

I apologize for the delay in posting and responding. No Elizabeth Smith had not been splattered, I’ve been told that the reddish splotches on her legs were produced by a combination of Anna Schuleit’s computer manipulated design and Chloë Z, Brown’s lighting.