Happy 50th birthday, Aureole! Sorry I missed the celebration. You certainly don’t look your age. When I think of all the ideas you spawned for your boss, Paul Taylor, I’m amazed at your daisy-freshness.

This is some season for the Taylor company: three weeks at the capacious, formerly named New York State Theater, instead of the usual two at the smaller New York City Center. Twenty-two works and repetitions of each stuffed into 21 performances that began March 13 and end April 1. Is Taylor trying to kill his dancers? Probably not. But Aureole aside, Taylor is looking back over a long career this season. Dancegoers too young to have seen Three Epitaphs (1956), Junction (1961), Big Bertha (1970), and House of Cards (1981) at their premieres may be startled by their transgressiveness (although that’s not a quality Taylor has ever completely gotten over, thank heaven).

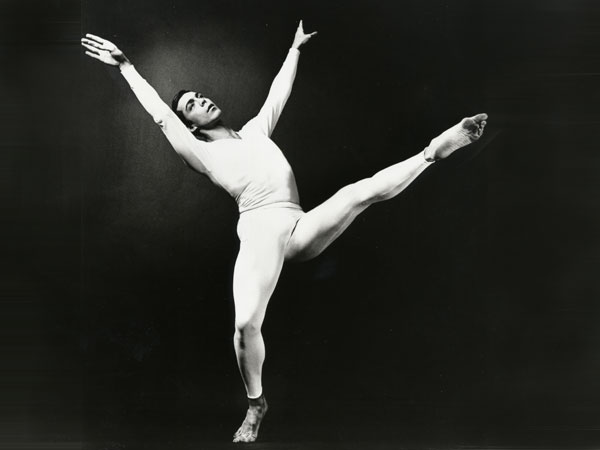

In the years since Aureole made its debut at the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College, it has been performed by numerous other companies, both professional and student ones. Taylor has often spoken slightingly of the dance’s simplicity, but that’s one of its virtues. Add to that a buoyant musicality, a sunny temperament, and a delicate wit. The five dancers who perform it to instrumental music by George Frideric Handel inhabit a landscape where the season is always Spring. I regret in a way that critics hailed Aureole as modern dance’s “white ballet.” The costumes may be white, but the robust people who wear them are nothing like the wraiths of Romantic ballet.

Early on, Taylor built a dance vocabulary that he adapts, augments, and varies in each new piece. The skimming runs of Aureole, the bunched-up jumps, the sideways hops with the dancers’ legs smacking lightly together in the air, the way their arms shoot up in a V-shape or wreathe around their bodies—these and more have found their way into other pieces. And Aureole’s tenderness and spirited lyricism reappear in different guises in Esplanade, Arden Court, Airs, and many others. The blithe and thrilling Mercuric Tidings (1982) is like Aureole pressurized—some of the same steps given new significance. To excerpts from two heart-stirring Schubert symphonies, its 13 dancers rush and leap in and out of formations far more complex than the five Aureole performers could create. Even in an adagio duet, intriguing complications arise. Three women in a hands-held chain weave around the loving exchanges between Amy Young and Michael Trusnovec, but there’s a fourth woman (Michelle Fleet), who’s special. She has utterances of her own to deliver, joining hands with the three only when she wishes to.

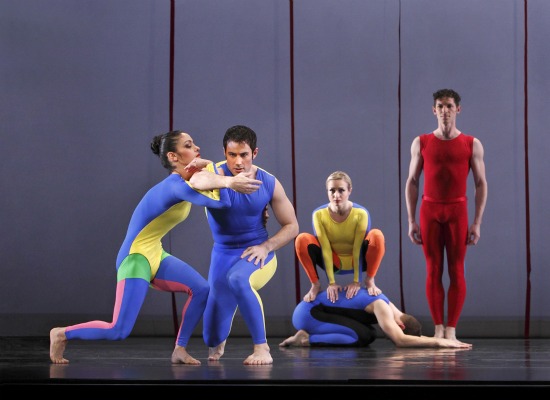

Junction: (L to R) Parisa Khobdeh, Robert Kleinendorst, Jamie Rae Walker atop Michael Novak, Sean Mahoney. Photo: Paul B. Goode

It’s fascinating to see Junction, made the year before Aureole. Here too, Taylor used baroque music (excerpts from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Solo Suites for Cello, Nos. 1 and 2), but in this case he was investigating how music and dance might intersect and being perverse about it. Instead of yielding to Bach’s tempi, he set slow walks to fast music and rapid steps to adagio passages. For instance, a slow-motion cluster of dancers, travels on a diagonal, each of them doing something different within the group, while the cellist (on tape, alas) makes the strings jitter and buzz.

Junction, however, isn’t a lyric piece. It’s in the family of Taylor works that includes the Dante-esque scramblings of 1963 Scudorama and the inner-beast elements that creep into the brilliant 1976 Cloven Kingdom (programmed again for April 1). The acrobatic and contortions of Junction, however, are cheerful. Santo Loquasto’s costumes and Jennifer Tipton’s lighting set that up for us. Men and women alike wear unitards—maybe one color on the front, one on the back, and two others on the legs—that suggest latter-day harlequins.

The cast of eight is, I believe, slightly larger than the original one, and two elements have been eliminated. At some point in the 1961 version, a pair of carpet strips were unrolled for performers to stride along, then later rolled up and stashed away. Also, dancers spelled one another at folding a tablecloth, until only a very small package remained to be taken away. This heralded the witty little passage in which one small bundled-up seated woman (in the current production Jamie Rae Walker) is ceremoniously carried across the stage, passed among three walking men, until the last one bears her offstage.

The first image in Junction, when Walker is squatting, frog-like, on the bent-over back of a kneeling figure (Michael Novak), establishes a vocabulary that often seems animalistic or buggy. In contrast to the ongoing stately walking, dancers face each other in combat; a sharp contraction of the spine powers a hurling gesture. They also, at times, shudder, as if to slough off a skin, or bend over and wheel their arms behind them. Sean Mahoney has a solo that’s 90 percent flailing. Their bent-legged cartwheels and somersaults on and offstage give them the look of wacky acrobats. In this, Taylor introduced the image of a woman stepping onto the back of a man on all fours, or standing on his stomach (as a woman does in the 1975 Esplanade, but in a curiously loving way). You could consider the delightfully eccentric Junction as a harbinger of Aureole. With the former, Taylor had tried not dancing to beautiful music. Why not make friends with it?

His new Gossamer Gallants (title courtesy of Herman Melville) dives gleefully into insect imagery. In this comical take on an old trope, however flirty and helpless and silly women look, they can whip a man into shape or eat him alive. And, of course, in some species of the insect world, a male can look forward to post-mating death (see Jerome Robbins’s grimmer The Cage). It was a canny move on Taylor’s part to set his joke-filled piece to dances from Bedrich Smetana’s The Bartered Bride. (How many times have these fine lusty, folksy melodies been played on WQXR? Too many to count.)

Loquasto has desgned an elaborate backdrop that suggests a circular, splayed, birds-eye view of an ancient European town plaza, beset with phallic towers. The 11 cast members wear unitards—dark and patterned for the men, Granny-Smith green for the women—with matching antenna-ed hats and trailing “gossamer” wings. These creatures make jabbing and preening gestures, rub their hands together, and zoom across the stage, but the stereotypes they represent are human. The horny men have gathered for a boys’ night on the town. Pheromes are in the air. The twittering women mince on in pairs, as if they wear invisible spike heels, and whisper conspiratorially, pretending to be unaware of the men panting behind them. Whatever they exude, it makes the guys crawl after them or pass out.

The jokes are good. Fleet has a languid solo that induces Mahoney and Trusnovec to spread a glittery cloak (an abandoned wing?) for her to step on. All the way across the stage. By the end of Gossamer Gallants, the women are chasing the now-terrified men, banging their heads together, riding them offstage, tackling them to the floor, and dragging them away. Tipton turns the sky red. That’s sex for you. This entertaining, silly-smart confection can be seen again on March 27 and 31.

Occasionally Taylor makes a dance whose personnel are damaged, weakened, diseased, or out of sorts in some way. I’d forgotten all about House of Cards, which premiered in 1981. It’s set to Darius Milhaud’s La Création du Monde, a score written for the Ballets Suedois in 1923, the year after the composer visited Harlem during a sojourn in America and loved what he heard. Taylor doesn’t follow the jazz-tinged score’s creation-myth scenario—not exactly that is. You could see the opening section as an analogue to the Old Testament God stirring chaos around like a stew in the making. Nine dancers in mostly red and black costumes circle tightly around a crouched, silver figure. Various ones of them fly out and return, but even as dancers gradually leave the ring, those remaining keep circling. The figure rises. It’s red-haired Heather McGinley, one of the tallest women in the company. She’s wearing an amazing silver gown (costumes by Cynthia O’Neal) that makes her look like an amalgam of the Statue of Liberty, a well-to-do fashion icon of the 1920s, and the Chrysler Building. (The Chrysler Building itself appears at the very bottom of a huge painted scroll by Mimi Gross that hangs upstage right and rolls toward the ceiling throughout the piece, bearing images of a door, an armchair, a vintage radio set).

House of Cards is almost too mysterious for its own good, but enthralling nonetheless. This silver goddess-cum-matriarch of an unruly clan has several aspects. Two of the men cuddle up to her and nestle their heads against her, then upend her. Once when she’s held up she spreads her legs, and dancers somersault out between them. When Walker dances a mini-solo, she stands in the background making understated gestures that suggest a conductor or puppeteer. At the end, she waves them all offstage into their lives without her.

Taylor evokes the jazz age via rough-cut Charlestons and other loose-limbed dances. What’s so interesting about this revival is not only how hopped-up everyone is, but how tired. Too much illicit booze, maybe, and too many late nights hoping Josephine Baker would drop by. These lethargic acrobats even take time-outs for sleep (when Francisco Graciano lies supine, two women pillow their heads on his body). House of Cards receives its last performance of the season on March 31.

Taylor’s “serious” new piece, The Uncommitted, received its first performance at the American Dance Festival last summer. It was created in honor of Charles L. Reinhart; 2011 marked his final year as director of the Festival, a post he had held since 1988. Reinhart also managed the Paul Taylor Company from 1962 (Aureole’s debut year) until 1968.

How many times have I used the word “enigmatic” while writing this article? Not once? Surprising, but helpful. The Uncommitted is set to music by Arvo Pärt: his Fratres, Mozart-Adagio, Ricercar, and Summa. Pärt’s brand of minimalism, indebted to Gregorian chant, often swathes ringing tones in an echoing continuum. Whatever the instrumentation, the effect is haunting, and many choreographers have turned to Pärt when seeking a misterioso ambiance.

Taylor is able to transcend the cliché and use the music’s wavering sweetness to striking effect in creating images of both brotherhood and overwhelming solitude. What a craftsman he is! In the first section, nine of the eleven dancers have solos. The first person to perform alone (Bugge) draws an imaginary circle on the floor into which each succeeding soloist is slotted. As each one is ending, all or several of the other performers rush onto the stage, absorb that person, and shed another. Each time, the transition is different and surprising.

The solos themselves differ in emphasis. Robert Kleinendorst jumps, legs bending under him in a diamond. Fleet fall to the floor and rolls, Young slides into her moves with slow tension, Parisa Khobdeh, her hair unaccountably wild, shudders and spins faster and faster.

The performers pair up, not always successfully. Kleinendorst puts his head on Bugge’s shoulder, but, in the end, they push each other away. Graciano and Kleinendorst fight fiercely, realistically, while other couples struggle, slow motion, in the background. Trusnovec and Young seem bonded (he picks her up, cradling her like a child—an image familiar from Aureole), but they exit separately from their first encounter and end the piece by again going their ways alone— not without regret on her part.

The people in The Uncommitted (to be shown again on March 30) are apparently members of a community. Everyone wears similar red-and-blue-floral-print unitards by Loquasto, with little transparent skirts for the women. They form alliances, dance in trios, unite in formal patterns, but nothing adheres for long. The dance is both satisfying and unsatisfying; incompleteness is Taylor’s intended theme, and he articulates that beautifully. But I’m left wondering what commitment would mean to these people in dance terms (and what the lack of commitment in today’s world signifies).

Taylor is as good at lust as he is at innocence. And he’s expert in sleaze. The 1970 Big Bertha is a dance so thoroughly nasty that you might want to take a bath after seeing it (or at least rinse out your mind). That it’s also brilliantly constructed makes it all the more horrid. The dominant figure in in the original cast was Bette de Jong, now Taylor’s invaluable rehearsal director (she also played the more benevolent leader in House of Cards). Now Young has taken over the role of the red-white-and-blue, nickel-gulping fairground automaton. Her jerky motions to band-machine music mesmerize an all-American family into depravity. The mother whips off her skirt and grinds her hips, oblivious to the fact that her husband is raping their daughter behind the booth.

When the piece begins, collapsed figures back slowly out of the light. So Big Bertha has played her game before. This time, she gets Dad up on the platform with her as her consort, while the band, ironically, plays “When The Saints Come Marching In.” The performers are all terrific—Young, frightening as Big Bertha; Fleet, proper, then abandoned as Mrs. B; Eran Bugge wonderfully frisky and innocent (at first) as Miss B.; and Trusnovec, stupefying as Mr. B. gradually, confusedly, yields to his inner beast.

Maybe Taylor needed a short piece to pair with Big Bertha. Whatever other reason he had for making House of Joy is still unfathomable. (The two works will be performed on the March 31 and April 1 matinees). House of Joy is not a dance but a semi-comic mimed drama. It apparently aspires to being meaty. Donald York composed a lively score, and Loquasto designed a marvelous set that looks like an Edward Hopper cityscape, complete with a ricketty whorehouse. This establishment is staffed by five women, one of whom is a man. Three shady “Procurers” (James Samson, Francisco Graciano, and Michael Apuzzo), one by one, bring clients: a sailor right out of Jerome Robbins’s Fancy Free (Mahoney); a doddering old man (Kleinendorst—amazing); a tough female biker (Parisa Khobdeh—also amazing); and a shy college boy (Michael Novak). The prostitutes are Laura Halzack, Walker, Aileen Roehl, McGinley, and Jeffrey Smith. The jokes are more or less predictable: Walker wears a false fat belly and displays it brazenly. Khobdeh needs two women. The kid has no money, so all three pimps beat him up. Halzack, who fancies him, makes a sad gesture, and the curtain descends. What? That’s it?

Taken as a whole, the Paul Taylor Dance Company’s season is a feast for those who love his work (and it helps greatly that ticket prices have been kept low; $10 seats exist). The more you see the dancers in different works, the more wonderful they reveal themselves to be. On view this last week of the season (in addition to those pieces already mentioned) are the masterworks Promethean Fire, Beloved Renegade, and Esplanade along with a rich Taylorian variety of pieces: the much-loved Piazzolla Caldera, the brilliant early comedy Three Epitaphs, Syzygy, Brandenburgs, Troilus and Cressida (reduced), Oh You Kid!. And, oh yes! Aureole.

Well written and insightful.

Amen to that, Jim Novak.

I love Big Bertha, which was performed in San Francisco in conjunction with a conference on Taylor quite a few years ago. Bette de Jong was on hand to talk about it and many other roles she originated, fascinating. I wish I could jump on a plane and see Promethean Fire performed at what I think of as the People’s Theater, and not the right wing millionaire’s, but I can’t. I hope Deborah will write about it, before she succumbs, frothing at the keyboard, to March Madness, god forbid.