(L to R) Chelsea Lynn Acree, Noah Vinson, Maile Okamura, Amber Star Merkens in Mark Morris's A Choral Fantasy. Photo: Juliete Cervanted

Ludwig van Beethoven must have had more stamina than he’s usually credited with. If you research his Fantasy in C Minor for Piano, Orchestra, and Chorus, Op. 80, you find that its first public performance in 1808 ended a program that lasted four hours and included among its nine items the premieres of Beethoven’s Fifth and Sixth symphonies (conducted by the 38-year-old composer), his Fourth Piano Concerto (played by the composer), and three movements of his C major Mass. No wonder he forgot that he had cancelled a repeat in the Fantasy’s second variation and went ahead with it, while the other musicians obeyed his original orders (the results that, wrote one assisting musician, “sounded not altogether edifying”).

Enough disarming trivia. Beethoven’s program closer, to which Mark Morris has set his beautiful new A Choral Fantasy is no dreamy meander. Sixteen years later, the composer built the “Ode to Joy” that closes his Ninth Symphony on elements of the theme that’s varied throughout the Fantasy’s many-sectioned second movement (and its finale). Despite sighings and tricklings away and soothing moments, this glorious music aspires toward triumph, with words that sing of nature’s beauties and of the art that offers them up to the heavens.

Thinking back on the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s March 1 premiere of the Morris work, I don’t think it would be a good idea to associate dancer Amber Star Merkens with the busy Beethoven at that 1808 concert, or too closely with the solo piano. It is nevertheless true that she, along with pianist Colin Fowler, exhorts, leads, consoles, and sustains the 14 dancers who give a dancing presence to the strings and woodwinds of the Mark Morris Dance Group Musical Ensemble (Stefan Asbury, conductor) and the voices of Trinity Choir (Julian Wachner, conductor). It is also she who, after a very brief solo to the first movement—an Adagio—seems by her gestures to pull the others onto the stage.

Isaac Mizrahi has costumed all the dancers identically in what look like trim green tracksuits—high-collared and sleeveless. Tapes both narrow and wide form an X on their chests and a sort of harness effect on their backs; curly gold braid runs down the pantlegs. Depending on the movement at any given time, the performers can make you think of soldiers, of athletes, or of school crossing guards. Michael Chybowski’s lighting saturates the backdrop with colors—by turns red, blue, green, pearl. For some reason, the musicians pause for long seconds between the sections, and we stare at the empty stage, waiting for the next onslaught of dancers.

They enter running, leaping, or marching, disperse and re-enter. In one smart maneuver, a line marches in one direction and another heads toward the opposite side of the stage, as if they’re ready to engage in separate offstage battles. Two squads arrive simultaneously in contrapuntal leaps and crouches. Dallas McMurray and William Smith III engage in a combative arm game in one corner (you strike, I block). Before long, the space has become a playground with three people here, four there, five over there. They uncoil in chains, cluster to lift another person high, fall to the ground.

Merkens, the leader, can appear unexpectedly—often in the quieter piano passages— and leaves without warning. (I’d have to see the dance again to understand all the musical correspondences that engage Morris).In the end, Morris reassembles elements of all the variations he has concocted, while the singers unleash Beethoven’s paean to love and strength, to harmony and grace.

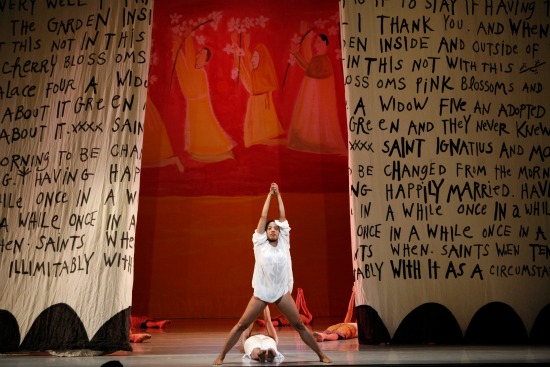

(L to R) Merkens, Garrison, Okamura, Rita Donohue, Laurel Lynch, Acree in Four Saints in Three Acts. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

At the BAM programs, A Choral Fantasy was preceded by Morris’s charming 2000 visualization of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, which premiered in New York in 1934 with an all African American cast. Both music and choreography have a sturdiness and a lilt that captures the faux-naïve quality of Stein’s words (sample: “Saint Teresa and Saint Teresa and Saint Teresa Seize and Saint Teresa might be very much as she would if she very much as she would if she would to be wary”). In this work, Morris’s close setting of steps and gestures to the text’s images and the music’s notes enhances the opera’s subtle traces of primitivism. The reiterated dotted rhythm of “Saint Te-re-sa and” powers many of the festive dances among the cohort of saints led by Teresa of Avila and Saint Ignatius Loyola—mystic and soldier.

These two having been Spaniards, Elizabeth Kurtzman has dressed the women in full, swishing skirts topped by cream-colored shawls, and Morris has introduced spiced versions of dances like the Sevillanas and, maybe, the Valenciana. The bare-chested male saints, however, wear white pants that make them look like Mexican peons, and Maira Kalman’s several delightful painted backdrops also evoke Mexico with their red-orange-pink juxtapositions. The dancers’ formations and blunt, buoyant movements remind me of the clay “santos” of the American Southwest.

The solo singers voice the various saints, and two, a Compère and a Commère, sing the stage directions, while the chorus comments. Listening and watching Four Saints for the second time a decade after its premiere, I’m struck by how Morris makes dance sense out of the playfully surreal words, creating his own games. In one scene, Saint Ignatius and Saint Teresa act like doorkeepers at a select nightclub deciding whom to let through the gap in the front curtain that bears Stein’s unevenly printed libretto. Maybe they’re going to a church picnic, maybe into heaven.

I’m also struck by the earthiness of this gathering. We might as well be at a village wedding, or a feast-day pageant in which the nicest girls and boys in town get to play saints. Once, the curtains part on kissing couples, and the communion between Ignatius and Teresa is fond and physical. Michelle Yard as Teresa projects a spiritual rapture, but it’s produced by her joy in all that she sees. Then there’s her costume. This beautiful, voluptuous woman is wearing a full, filmy white smock that doesn’t begin to hide her white underpants. No wonder Saint Ignatius (splendidly performed by Samuel Black) is smitten.

A program of Mark Morris’s works often sends most spectators home elated. In the case of these two dances, the mingling of what you see and what you hear creates a vision of instrumentalists, singers, and dancers gathering ardently together in the fields of the music—rain or shine.

In regard to those supremely musical dancers, Yard tore a calf muscle in the middle of the second performance, and Rita Donohue, who also dances the role, stepped in. Sad news, a gallant save. The accident ought to remind us that every one of the MMDG members is vital to the work, memorable, and, in some deeper sense, irreplaceable.