The Hindu god Shiva is sometimes pictured in Indian art and philosophy as half-man, half-woman. One beguiling interpretation of this vision is that he ceded half of his body to his beloved consort, Parvati, to show how much he loved her. In Hinduism, the union—or desired union—between masculine god and desirous female soul is the subject of many ravishing poems and dances. But as the three members of the Nrityagram Dance Ensemble so beautifully demonstrated during the company’s season at the Joyce Theater (March 20 through 25), a single dancer may become both sought-for god and yearning woman in the course of a dramatic piece.

These dancers—Surupa Sen, the group’s artistic director and choreographer; Bijayini Satpathy; and Pavithra Reddy—live and work in the Nrityagram Dance Village, an arts center and school in Bangalore. The ensemble has appeared at the Joyce twice before, in 2005 and 2008. The new program, Samhara, shows even more powerfully than the two previous ones the masculine element of the Odissi style that the women practice so expertly. The title can also mean a braiding together, and in two numbers that Sen choreographed with the assistance of Heshma Wignaraja, members of Sri Lanka’s Chitrasena Dance—Thaji Dias and Mithilani Munasingha— juxtapose their own bold style, known as Kandyan, to that of the Odissi dancers. You can even imagine that, as the two groups of women worked together on this project, subtle influences threaded between them as fluidly as the dancers weave patterns around each other onstage.

When I think of Odissi, I tend to picture first the sensual image of the female body that it presents. Even though the dancer’s rhythmical footwork may be crisp and strong, she settles into the s-shaped undulation that you see over and over on temple carvings in South India. It’s as if the erect Bharata Natyam dancer—heels together, feet turned out, knees bent—has melted a little in the sun; her hips swing to the side as she shifts her weight slightly over one foot, her ribcage shifts in the opposite direction, and her head inclines toward the hips.

But as the opening Arpanam shows, these seductive stances are only part of the picture. A prayer to Parvati begins with Srinibas Satapathy sounding his bamboo flute in darkness, and as we gradually glimpse the dancers in shadows, the drummer (Sibasankar Satapathy) answers. We hear the poem invoking Shiva’s beloved. But it’s not long before bounding jumps, turns, and strong kicks counter the languorous air. Sanjib Kunda’s violin and the drone of Jateen Sahu’s harmonium enter the mix (along with Sahu’s chanting of the rhythmic syllables that incite the performers’ stamping feet). A dancer lifts a leg and—whap!—smacks it on the floor as she drops into a lunge. Sen arches her back with the force of an exclamation point.

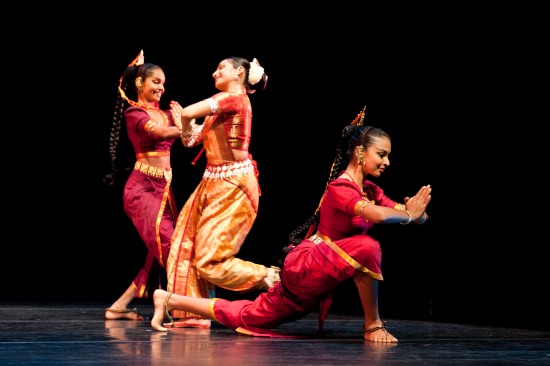

Odissi originated as a solo form, but choreographers like Sen have broadened its purlieus. Satpathy and Reddy gesture to each other, while Sen appears to have a spiritual experience (“Grant us the vision to behold you within,” say the words). The women may dance in unison; they may not. And a surprising counterpoint enters the picture when the Kandyan dancers arrive onstage. (It may be now that the prayer yields to the dance expressing the five elements—earth, water, fire, air and ether). It’s as if a school’s bad girls had suddenly sauntered into the playground. They’re not, of course, bad; they’re charming, and the smiles rarely leave their faces. But they appear to have come from another dance world. Dias and Munasingha are both tall and very slender; their draped pants stop just below the calf, so their legs look even longer; the expanse of bare torso between their waists and the bottoms of their bodices seems as slim and flexible as a sapling. These women aren’t given to flirtatious glances and sensuous hips; their long braids swing as they spin and lunge and stamp. Their own accompanist, Udaya Kumara, plays his big horizontal drum for them when the Nrtityagram women leave the stage temporarily.

(L to R) Two groups mingle: Mithilani Munasingh, Pavithra Reddy, and Thaji Dias. Photo: Nan Melville

Both Sen’s two major Odissi works on the program focus on male gods. One, a duet by Sen and Satpathy (both superb), praises Shiva and asks a favor of him; the other portrays Krishna at a bad moment in his day. Invoking Shiva presents powerful images in tune with those in the accompanying poem: the river Ganga that descends from the god’s matted locks, his burning third eye, his cosmic dance in which the universe is destroyed that it may be re-created. The gestures and movements illustrate such events as this: “Opening your third eye/ you burnt to ashes/ the God of Love, the five-arrowed Kamadeva, /disrupter of your meditation.” We see Sen meditating, see Satpathy shooting the five arrows, Sen rising startled and angry. But drama is porous in Indian dance; events foam up, sink, and rise transformed. Seconds later, the two women are dancing in unison, turning like the universe. The vision of Shiva flames differently in the quiet plea of the last words, “Dance/ on the funeral pyres/ of my heart/ and release me/ from this universe.”

Anyone who has attended concerts of Indian dance is accustomed to seeing the adorable (and adored) blue-faced god Krishna through the eyes of women who crave his attention. Dancing the words of poems, a solo performer may adorn her hair with blossoms, her neck with garlands. She may peer into the distance—he promised to come! She may wilt under the burden of unassuaged love. She may stamp her foot and flash her eyes at having seen him romancing another.

Surupa Sen in Krishna's Lament. Photo: Nan Melville

Instead, Sen has chosen to illustrate a poem from the 12th-century Gita Govinda in which the speaker is Krishna. His great love, Radha, has become angry with him—maybe when she spied him in amorous play with a bevy of milkmaids (a famous episode in his story)—and walked away from him, deeply pained. The theme—and you see Sen smite her forehead in anguish—is “Damn you, Krishna, for not stopping her!” Krishna, hungering for her forgiveness, may seem like any philanderer, but this is serious. Radha symbolizes all those who seek spiritual union with a divinity. That union must be preserved, and the Hindu gods—even the usually carefree Krishna— are as responsible for its maintenance as their worshippers. Sen is marvelously expressive as the repentant Krishna—gazing searchingly after Radha; sinking into a split, fists raised; falling dramatically to the floor. The spiritual message evokes a situation many women know well—one in which they smack their own foreheads and say, “Ah, men!”

The opening dance gives only a taste of the choreographic collaboration between the Nrityagram dancers and the Chitrasena ones. The final Alap is a richer coming together of the two groups and their musicians. Now the choreography shows unison patterns, contrapuntal passages, question-and-response exchanges, juxtapositions of stillness to motion, and rhythmic displays. The stage is full of life. I even thought I saw a bit of pantomime: a brief game by the Sri Lankan beauties, in which dice were cast, someone cheated, and money was offered.

How marvelous! Three plus two women show us a shifting picture of female strength and male weakness, and vice versa, as well as the ways in which desire—whatever its object—molds the body, the face, the nimble fingers. The music is honeyed and caressing, but underneath lies the inexorable percussive beat.

This writing is as richly textured as the performance must have been, wonderful reading on an exceedingly rainy morning in Portland. Many, heartfelt thanks.