Ib Andersen didn’t move to Phoenix in 2000 to become artistic director of the Arizona Ballet. According to a recent interview, when he took on the job he was already in Arizona—loving the clear light, open sky, and sere landscape, and painting in his spare time. He may not have much spare time these days. During his tenure, the company debt has been erased, the board has labored to raise money, and the number of donors has grown, along with the company’s repertory and the level of its dancing. In August Ballet Arizona and its school will move into a renovated warehouse, with studios galore, plus a 300-seat black-box theater.

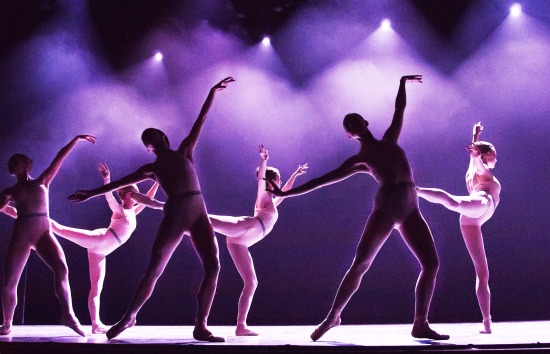

The company’s New York debut attests to the perseverance of Andersen and his colleagues. The dancers’ clean lines and unmannered performing derive in large measure from Andersen’s experience as a principal dancer in the New York City Ballet from 1980 to 1990 (and possibly, too, from his previous schoolboy-to-star years in the Royal Danish Ballet). At the Joyce Theater, several apprentices and alumni of the school joined the 26 company dancers in Andersen’s Play, and while some of those onstage are less experienced than others, everyone dances with precision, fluency, and a quiet fervor. Ballet Arizona, like other companies directed by former NYCB principals (Edward Villella at Miami City Ballet and Peter Boal at Pacific Northwest Ballet), has built its reputation in part on its fastidious presentation of ballets by George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. Learning these works helped groom the dancers to be quick-footed, expansive in space, and musically alert.

Andersen’s 2007 Play was clearly designed to introduce individual dancers to an audience and show that the company could master various styles. It’s a smorgasbord—albeit a well-assembled one—building from classroom basics to the clever patterns and bright, rapid steps engendered by Igor Stravinsky’s Suite no. 2 and Pulcinella Suite. The hour-long Play whetted my appetite. I’d like to see the Arizona Ballet in its Balanchine repertory, in its Nutcracker, and in Andersen’s upcoming Topia, a collaboration with the Desert Botanical Garden and designed to be performed in a space within the garden.

The opening number in Act I of Play is set to Mozart’s Variations on “À vous dirai-je Maman,” aka “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.” In the course of its basic, clean-cut group passages, Andersen manages to display in short solos all five of the section’s women (Jillian Barrell, Tzu-Chia Huang, Kanako Imayoshi, Natalia Magnicaballi, and Breanne Starke, and all its men (Zherlin Ndudi, Gleidson Vasconcelos, Michal Wozniak, Slawomir Wozniak, and Astrit Zejnati—a number of the company’s male dancers come from Eastern Europe). Here comes a shooting-star leap, here a slow unfolding of a leg into the air, here a spin, here a skimming rush offstage, here a sustained and controlled balance. It’s a pretty strenuous section in a restrained way, and the performers lie down for a brief rest, letting Mozart play on before the final bout.

Two aspects of the ballet become evident at the outset. One is that Andersen has a brilliant colleague in lighting designer Michael Korsch. Korsch keeps the lighting cool and clear during this opening for the ten dancers. Tiny suspended lights twinkle both behind and in front of the dancers, situating them in a starry universe. Throughout Play, his contributions define space both architecturally and environmentally, never becoming flashy.

It’s also apparent that Andersen knows music and chooses it well. When choreographing to Mozart’s variations, however, he tends to wed every step to the rhythm proper of the musical passage—rarely fitting in more or fewer steps than there are notes in a measure. That may have been a deliberate choice in the sweetly plain first section, but it carries over into the ensuing quintet to the Andante from Schubert’s Octet in F major and the section set to Benjamin Britten’s Prelude and Fugue for 18-Part String Orchestra (all heard in recordings at the Joyce). In the second half of the piece, when the choreography grapples with Stravinsky’s complexities, Play becomes more lively interchange between music and dancing.

The Schubert piece engenders a charmingly flirty game for four come-and-go men (Ilir Shtylla, Shea Johnson, Myles Lavallee, and Roman Zavarov) and an alluring woman (Paola Hartley) wearing a sparkly fuschia dress (costumes by Andersen). Sometimes one man gets to date her; sometimes they all collaborate with genial nonchalance (you hold her leg this time, pal) and toss her high. Britten’s music is fuller, darker, and more prone to discord. There’s quite a bit of lying down in this section too, but its cast of 11 women also march and pose and show off their arabesques. Andersen seems often to work with simple means, plaiting an economical number of steps into attractive patterns.

The last two parts of Play’s Act I are set to music by Arvo Pårt. The first, appropriately is the composer’s Cantus in Memory of Britten, and Andersen has chosen to grace it with two identical, simultaneous pas de deux, excellently performed by Huang and Shtylla plus Michelle Mahowald and Cavanaugh. Another of Pårt’s dreamy, softly chiming scores, Festina Lente, accompanies an earthier pas de deux for Magnicaballi and Zjenati, The expression borrowed for the title can be translated as “make haste slowly,” but there’s nothing oxymoronic about the sensual coupling of these two. Inhabiting a spot of turf under a warm light, they spend most of their time on the floor in slow, heated, almost somnambulistic foreplay. Their minimal clothing shows off musculature that glints as if oiled. This is one of those duets that hint ever so artistically at Neolithic matings (drag the woman along, check her legs for length, twist her around your manly body in interesting ways, slide her onto your bent back and lug her to your lair). Yes, the company can do that kind of stuff too. Magnicaballi is eerily gorgeous, and my eyes fasten on Zejmati every time he’s onstage in Play—not just because of his technical expertise, but because of the way his focus enlivens the space around him.

There’s an intermission between Play’s two acts, and when the curtain goes up on the second, you can feel the audience’s spirits lift. To Stravinsky’s Suite no. 2, Andersen plays around with eight women and four men—the former in tangerine-colored outfits with flippy little skirts, their partners in tan tights and blue-green vests. How many eye-engaging patterns can the choreography pull them into? Three trios, a four-spoked Texas Star, lines, and more.

Throughout the six sections of Stravinsky’s marvelous Pulcinella Suite, Anderson deploys his cast in all manner of designs and rapid steps— close follow-the-leader canons, hand-in-hand chains, perky little jumps— having no truck with the narratives lurking in the music. The “Tarantella” for four couples and six women projects a little Neapolitan spiciness, and the “Gavotta con due variazone,” is an enjoyably comradely trio for Barrell, Huang, and Zejnati. The choreography continues to bring various elements to the foreground—here a duet for two men, here women entering to thread through a forest of men.

Andersen manipulates his material adroitly, creating choreography that’s seldom thrillingly original, but always very good to look at. As I said earlier, Play’s game-plan is to show what these dancers are capable of. It ends up making you want to see more of them. I count that a success.

Having seen the program, I enjoyed this review. My own take is a little different–I found the choreography quite original in places and both the choreography and the dancers exceptionally sensitive to their music–but yours is accurate and valid. Just a note to add that Andersen also designed all the costumes.

I saw the company in Phoenix, at the end of Andersen’s first season as a.d. in which they did a highly credible performance of Billy the Kid. At that point, they were not I thought capable of dancing Balanchine, though I knew they would be. I too wish I could see Topia; my great-aunt, Virginia Ullman, was a founding board member of the Desert Botanical Garden and it’s a magical place. Andersen has certainly rescued that company, which was very close to folding when he took over. I’m pleased indeed to read Deborah’s customarily vivid description of the dancing, which is almost (but not quite) as good as being at the performance myself. Thank you, ma’am!

“…having no truck with the narratives lurking in the music.” Always fascinating to contemplate the choices choreographers make when working with demanding (in several senses) music. Thank you for this.