In January, 2011, one-and-a-half years after Merce Cunningham died, the second half of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s two-year Legacy Tour began in Hong Kong. It ended at 10:00 P.M. on December 31 in New York. The immense crowd of spectators in the Park Avenue Armory applauded and cheered the dancers for many minutes, as if keeping them onstage, bowing over and over, not only showed them how much we treasured them; it delayed the moment when they would thread their way through the crowd to the dressing rooms, and the company Cunningham founded in 1953 would cease to exist.

People in the other 35 cities visited during the tour had already said their goodbyes. Moscow, London, Jerusalem, Mexico City, Paris, Marseilles, Seattle, Austin, Chicago, Washington D.C., Minneapolis, and more had seen selections from the repertory of 14 dances with which MCDC traveled. Perhaps dance companies in some of those cities will mount works licensed from the Merce Cunningham Trust (American Ballet Theatre and London’s Rambert Dance Company have already done so). The 14 superb performers—the last among the 118 who danced in MCDC over the years—will separate and go on to careers in other companies. But as one of them, Daniel Madoff, said after the last glorious Armory performance, it was as if Merce had died all over again.

And, in a sense, it was Cunningham himself that we were celebrating and mourning. His work is wired into the cells, muscles, sinews, and brain tissue of the dancers who studied with him and on whom he created his extraordinary pieces. A dance exists fully only when it is being performed, and when his company shows us his work, we see his genius in its purest state.

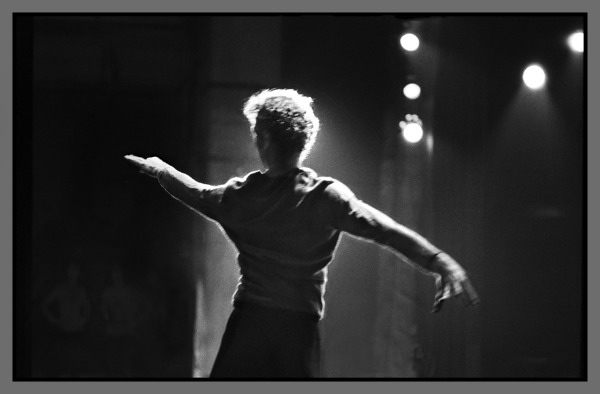

Long before 9 P.M. on December 31st, the Armory is packed. This is the second show of the day, the last of six performances. The end. Some spectators crowd onto one of the six platforms (about 10 feet high) placed around the vast space. Others wander at will, or find seats on benches and chairs that ring each of three square, raised stages. The dancers, still wearing practice clothes, test the spaces and their bodies. Standing at the rail of one of the platforms, I can look down at Stage A (the one nearest Park Avenue) and watch Andrea Weber sail beautifully into some suspended, backward turns on one leg. Stage B, the middle one, has barres for the time being, and a dancer or two is making use of them to stretch. Brandon Collwes lies on his belly, sliding his thighs back and forth over a Styrofoam roll. On Stage C, way east by Lexington Avenue, company members are jumping a bit. That’s Melissa Toogood, I think, launching herself into a gorgeous leap.

The Armory performances are all Events. Like Event #1, performed at the Vienna Museum in 1964 and in many indoor and outdoor sites since then, this final Event is a collage of sequences from Cunningham dances (over 20 in this case, long past and current). It has been arranged by MCDC’s Director of Choreography, Robert Swinston, but I believe the dancers have had some say about which solos they wanted to perform. The costumes by Anna Finke are new—gray unitards sparsely splotched with patterns in muted colors drawn from photos of Westbeth, where the company had its studio, and of the view from its windows. The music is also new—four separate scores by members of the MCDC Music Committee: Takehisa Kosugi, Director, David Behrman, John King, and Christian Wolff. Daniel Arsham designed the décor: eight suspended “clouds,” formed of clusters of white spheres about twice the size of tennis balls. The Events we used to trek to years ago in the window-rich studio on Westbeth’s eleventh floor were intimate—the dancers sometimes so close that the spectators lined up down one long side of the space could almost touch them, and their breathing provided a counterpoint to whatever music was played, yet the Armory Events create a kind of intimacy within the framework of a spectacle. We watch with particular intensity, wanting to remember as well as to see what’s in front of our eyes.

Spectators know to settle down when the dancers trickle away, and a few minutes after 9:00, the space becomes magical. Strings of little golden footlights surround each stage, and a ring of lights hangs above each. Beams illumine the suspended clouds and—sometimes—cast their shadows onto the stages (Christine Shallenberg created the marvelous design). A trumpet sounds from a balcony high on the western wall, and its call is answered by the remaining two trumpeters and three trombone players of TILT, who are stationed on other platforms around the space to launch Behrman’s Open Space with Brass. The effect is uncanny—part summons, part taps.

Over the next 45-or-so minutes, the dancers come and go, join and separate on the three stages. The timings vary among excerpts in the three areas, so few end simultaneously. If I scan across all the activities, it’s as if I’m gazing at an immense field of tilting, bending torsos; legs flashing high; and gusting jumps. Sometimes the images are diverse. At the outset, for instance, Weber is alone on Stage A—slowly, meditatively extending her limbs in an excerpt from Way Station (2001), while on far-east Stage C, Jamie Scott leaps into a balance on one leg; a few seconds later, Dylan Crossman and John Hinrichs join her and dance in energetic, side-by side-unison (this from the 1984 Doubles). By now Collwes is steadying Weber’s canted balances on A, while between them on Stage B, Silas Riener and then Rashaun Mitchell join Emma Desjardins, Melissa Toogood, Jennifer Goggans, and Daniel Madoff, who are already busy with some quick-footed stuff from the 1980 Fielding Sixes (because of an injury, Marcie Munnerlyn could not be with them this time).

But when Crossman continues on C alone, and Swinston replaces the duet on A with one of Cunningham’s own solos, and Collwes reappears on the now deserted B with another solo, there are a few seconds when all the complex overlapping calms down, and you see three male dancers performing three different selections in their separate worlds. A few minutes later, all three stages hold duets. Because Hinrichs and Krista Nelson perform a duet from Torse (1976) on B, while Crossman and Scott, Weber and Mitchell— flanking them on the two outer stages—dance the same excerpt from Cunningham’s last work, Nearly Ninety (2009), a trail over 30 years long traces and retraces its steps.

The program doesn’t provide the audience with information about who’s doing what when. Yet for me, as a historian-critic and long-time follower of the company, it’s wonderful to see Collwes shoot into bent-legged jumps and discover later that the excerpt was performed by Merce in Rune (1959), which reminds me of how aerial Cunningham was in his heyday as a performer. It’s moving, then, to contrast this with Swinston performing a later number of Cunningham’s with a chair—a solo that consists mostly of his moving the chair around and staring at it. You don’t, of course, need to know such details; absorbing the layering of material is enthralling enough. What matters are people dancing their hearts out—that is, dancing everything they know and feel about this epochal work.

Everything seems worth noting and remembering. Riener in a strange solo that involves pointing his fingers skyward; Weber and Scott grinning reassuringly, as they face each other in the little dialogue for forearms and elbows that I remember from Changing Steps; Mitchell and Crossman resting on the floor below Stage A, shaking out their thighs; Goggans falling again and again in a duet and Mitchell setting her on her feet every time. When Goggans performs on Stage B a long, amazing solo (made for Carolyn Brown in the 1965 Variations V), she becomes for a while a pole star around which the changing activities on A and C seem to revolve.

There’s much to marvel at in both the choreography and the performing. How many curious and meaningful ways Cunningham discovered for a man and woman to intersect—intimately but without heat, their limbs and bodies finding surprising connections and counterbalances. How interestingly he juxtaposed big, strenuous steps with curious gestures and twists, and flurries of quick steps with stillness. You remember how witty he could be when you spy Goggans, Scott, and Crossman attempt a journey hanging onto one another, despite how awkward their progress becomes. In wonderful, very different solos performed by Riener, Madoff, and Weber you see Cunningham’s overarching view of the dancer as a person both intensely alive to the moment and alert as an animal, yet serene—an observer, a discoverer, a risk-taker, someone who walks the earth with eyes open and ears pricked.

The four pieces of music are all exciting in different ways—sometimes caressing, sometimes assaultive, sometimes turbulent. Electronic sounds and the voice of a cello soften the notes of the brass players in Behrman’s score. King’s Astral Epitaphs involves the musicians of TILT with electronic elements that include the recorded voices of a chorus. Kosugi’s Octet (played second) is an all-electronic piece—ferocious at times. Wolff’s Song (For Six), which can also sound fierce, is performed live on piano, trumpet, French horn, double bass, percussion, and drums. That rich mélange of sounds ends the performance.

Amid all the glory, it’s sobering to recall that for much of his long career, Cunningham was often misunderstood, mocked, and disparaged. Although many people admired his daring and his genius, and found his dances profound as well as provocative, others walked out of performances—enraged by the dissonance of the music, confused by the lack of narrative, climaxes, and eagerness to please.

Considering that for many years, he and his company performed under difficult conditions before an uncomprehending public, he was, I’m sure, tickled by the adulation that his dancers have been receiving in recent years. And he might have been amazed by the rapt response at this final Event.

It was Cunningham’s decision to close the company two years after his death. To end it on a high, rather than letting in dwindle on without its creator was undoubtedly smart. But the tears are still drying. It’s not only a new year but a new Merce-less era in dance we have to get used to. Fortunately he gave us the new eyes needed to see whatever comes.

Lovely, just lovely, and no surprise there! thank you Deborah, from the heart.

It was an extraordinary last performance, and I had scribbled notes and sketches the next morning, hoping I could retain each detail in my memory. All I needed was the beautiful writing of Deborah Jowitt — you have captured the very essence of the night, and all that we were feeling. Thank you Deborah, for this most special review!!

Thank you Deborah for capturing a moment that was so special. Yes, for all of us who were lucky enough to study at the studio and see those superb dancers dance for the last decades…I had my student visa at the studio in 1980 and my experience there confirmed everything I had read about the technique and the dancing bf leaving Brazil. Thank you for the such wonderful writing!

Thank you for your eloquent article. Your words literally dance off the page with insight..

As much as I regret having missed this once-in-a-lifetime performance, Deborah’s moving and vivid account of the evening transported me as only great dance writing can.