Artists inevitably reveal themselves in their work, but some do it more overtly than others. Over the course of his career, Bill T. Jones has told us a lot about himself—not only in his choices of subject matter and his wonderfully poetic memoir Last Night on Earth, but while onstage dancing. Watching his solos, we learned about the large family he grew up in—about his mother Estella, his beautiful sister Rhodessa, his boyhood escapades. We knew from the dances that he and Arnie Zane made together that the two were lovers who had met as students at SUNY-Binghamton. Through their onstage conversations, we learned the names of their friends, teachers, colleagues, and the artists they admired (Louise Nevelson loomed large).

After Zane died of AIDS in 1988, Jones put his fear, his anger, his badly shaken belief in a merciful god, and his awareness of the persistence of racism into complex group pieces for the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, such as Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land (1990) Still/Here (1994), and the more recent Serenade/The Proposition (2008) and Fondly Do We Hope. . .Fervently Do We Pray (2009)—works from which his own stories never entirely disappeared.

Jones has also choreographed dances that were primarily about movement and music (some of them for other companies), contributed to plays and operas, and—with the Broadway hit Fela—branched into telling others’ stories without juxtaposing them to his own. He has now officially retired from dancing, turning into the hale, white-haired master who he once said (in the terrifying speech that accompanied his 1994 solo Last Night on Earth) he wouldn’t live long enough to become.

Yet his life is still before us in his new Story/Time, shown in six performances between January 21 and 29 in Montclair State University’s Alexander Kasser Theater as part of the tremendously valuable Peak Performances series. He sits center stage at a spare desk of modernist design with a cup of water and a row of Granny Smith apples in front of him and reads stories in a calm, but expressive voice, while his dancers storm around him.

The idea behind Story/Time is a structural one, borrowed from John Cage. In the composer’s Indeterminacy (1958), he sat onstage and allotted himself one minute in which to read each of the anecdotes he had written and selected for the occasion (he had over 100 to choose from). Like Cage, Jones relates his own experiences and those of people he knows or has read of, as well as his artistic processes and what happens in his garden, and these stories sometimes end with the kind of enigmatic punch line that make the composer’s so irresistible. Also, in homage to Cage, and to challenge his own processes, Jones allowed a few chance elements to govern the intersection of text and movement.

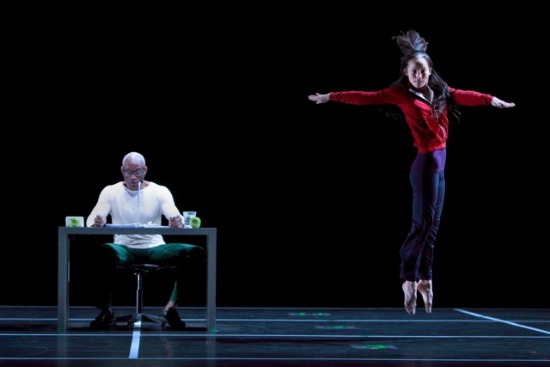

Left to right: Erick Montes, Antonio Brown (hidden), Talli Jackson, LaMichael Leonard, Jr. Photo: Paul B. Goode

In addition to the desk, the stage contains (intermittently) a sofa, a revolving chair, and two large, white, translucent two-paneled screens. The last, when put together and glowing in Robert Wierzel’s brilliant lighting, can become a box to contain dancing or reduce some performers to filmy echoes. When Jones tells of wandering through Amsterdam’s red light district, a screen becomes for a few moments a windowed room in which the ravishing Shayla-Vie Jenkins dances. A large clock suspended behind Jones counts down the minutes at the beginning of Story/Time and returns to continue near the end (a wise move to make it disappear for a while; being aware that, say, Jones might end up running overtime with a story takes attention off the dancing).

In 70 minutes, Jones reads over 50 tales, with time-outs in which Ted Coffey’s score becomes more prominent—sometimes chiming and whirring delicately with sounds of nature, once thudding so thunderously that you feel it in the pit of your stomach. The accompanying dancing is rich and fluent. Jones’s style balances looseness and precision; it’s silky without being indolent. The nine magnificent performers hurtle around and engage in push-pull maneuvers that have a self-perpetuating energy; but they also place their limbs with exactitude into slots of space-time, or pause in the action to watch and wait. They rush into clumps to receive one or another colleague as he or she races toward them and takes to the air. They make you sense the risk, even though they never fail to catch the flyer.

To reinforce the changing correspondences between movement and narration, Jones tells a compressed tale that involves a villainous landlord demanding rent, a rape, and several deaths; the performers enact it at top speed. The second time the story occurs, there’s a gender switch (for instance, the beautiful—and female—I-Ling Liu plays the avenging son). The third time, the text is absent. In some of the episodes, the words are explicitly tied to what we see. Jones speaks of his mother throwing herself to the floor and rolling back and forth upon hearing of her sister’s death. The dancers roll.

Much of the time, though, the spoken words don’t jibe with what we see at the moment, or they match it subtly (three men entangle in a trio shortly before Jones tells of a car ride with Lou Harrison and Virgil Thomson). The text also may resonate with something we heard earlier or will hear. It doesn’t matter that tall LaMichael Leonard, Jr. performs a wonderful solo that bridges a story about a boy’s growing out of short pants into long ones and a recollection of a painting by Joan Mitchell.

There are numerous beautiful, enigmatic images: dancers setting off puffs of smoke as they roll across the stage, or being carried on the sofa, almost silhouetted; Jennifer Nugent bending protectively over Erick Montes, who is suddenly naked. In one memorable vignette, Paul Matteson watches and occasionally helps Jenna Riegel and Jackson, as, on the couch, they assume intimate positions that are awkwardly, dreamily sensual without literally evoking the sex act. Boxed in by screens, the Taiwanese Liu dances while talking furiously in a language we may not understand.

Midway through Story/Time, all nine performers (I haven’t yet mentioned Antonio Brown) exchange their casual clothes (costumes by Liz Prince) and reappear looking ready to perform a number in a wholesome musical comedy. The women wear flowered dresses and the men sport flashy trousers with a geometric red, black, and white pattern (this when the music is at its most disastrous). But the new look brings out something that has been evident all along at various times: Jones likes—and is expert at—designing group choreography that creates vivid interplays of unison and counterpoint.

One thing bothered me about this bold, fascinating, and often deeply moving piece. The rhythm of the story-telling has a sameness that becomes enervating toward the end of Story/Time. Jones sometimes reads quickly, then has to slow down a bit; occasionally he sings instead. Often he has no time to make a clear break between anecdotes. My impression is that Jones wrote his paragraphs with the idea that each could fit into the span of a minute without too much trouble. But if you look at Cage’s little gems at the terrific website, www.lcdf.org/indeterminacy/, you’ll see that they vary in length, so that in order to fill a minute, some must be almost gabbled, while others need to be pocked by long pauses. Remembering Cage and/or David Vaughan reading some of them to accompany Merce Cunningham’s 1965 How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run, it comes back to me how expertly the readers sometimes drew words out or broke them into suspenseful syllables.

Story/Time represents a new direction for Jones, and not just in terms of acknowledging the change in his own role as a performer-choreographer; he’s seeing what it’s like to cede a little control. One of the tales he tells involves Max Roach, singer Abbey Lincoln (his wife), and Thelonious Monk. Monk, on his way out after listening to Roach’s drumming, turns back to say, “Next time, make a mistake.”

Ms. Jowitt, h ow well you know your craft, and theirs–whomever you’re reviewing. In this particular case, it’s a dialogue on which I am ever so happy to eavesdrop. Thank you.

Montclair is in my state, a not overly long drive up the GS Parkway, but I didn’t get there. But you did, and with your report I know exactly what took place. Thank you.

Ms.Jowitt

I am one of the nine performers from Mr. Jones my name is Erick Montes I just want to thank you for giving us the dancers members on the company an individual mention with such a care and respect,

In the other side I want to tell you that you way of writing it is sublime and is a pleasure to read you, Thanks.

Ms. Jowitt,

I was one of your previous students ‘ Graduate Seminar ‘ : TSOA/NYU

and as an MFA student I was also : ‘one-of-your-dancers’.

Your book ‘ Time & The Dancing Image’ – had just been published

and the book, and all of your vast knowledge & wisdom –

continue to endow my life with ever more passion for movement.

I send you my gratitude for this piece you have written for : BTJ/AZ Dance Company.

With Endless Respect & Admiration,

Catherine Kirsch

( @ NYU : Catherine Kirsch De Mattei )