Elizabeth Streb has the mind of a physicist, the heart of a circus performer, and a movie stuntman’s appetite for risk. Upping the ante while balancing all the factors involved seems to be what sustains her. In the 1980s, when she first started showing her work in small downtown black-box theaters or loft spaces, watching her performers topple—straight as boards, faces down—onto a mic’d mattress could make you wince and gasp. From December 14 through 22, 2011, in the Park Avenue Armory, some of Streb’s dancers—preparing in sight of the audience for her new Kiss the Air!—do those falls as a part of their warm-up, cushioning some of the impact on their tightly bent forearms. But later, in the section called “Human Fountain,” they launch themselves into space from the top tier of a three-storied metal edifice and fly about 20 feet down to land on their bellies (or backs) on a room-sized mattress over a yard thick. With their arms spread. That’s what you call progress.

No wonder the choreographer calls the members of SLAM! not just “action engineers” but “action heroes.” The exclamation point in the group’s name and that of the new piece is apt. Pow! Bang! Thud! Slam! Such sounds often act as the periods ending an event in this gravity-and-equilibrium show that Streb has constructed in and on the towers, bridges, and girders (by Streb and Hudson Scenic) that stretch down the Armory between two banks of spectators. For the first event, the mobile and highly vocal DJ/MC, Zaire Baptiste introduces the performers as, one after another, they grab handholds and zoom along zip lines from the north or south tower to splat against suspended mattresses that swing with the impact. Whaaap!!

Between feats, the performers, wearing red unitards by Andrea Lauer, head for spots of red light on the sidelines, gulp water, and remove or add harnesses and stuff, while Baptiste chivvies them on: “Ready dancers? Hold up your arms!” Those pauses are brief.

Kiss the Air! is Streb’s most circus-like performance yet. Three large video screens above either side of the Armory show footage of the performers at work—sometimes in outdoor locations—and later receive in-close, live-feed images of them (Projection design, Erik Pearson; Cinematographer, Alex Rappoport; Live Camera Operators, Sarah Lasley and Tiffany Hopkins). Robert Wierzel’s lighting design makes ample use of color changes and follow spots (or, before the show starts, spotlight beams that just wander around showing off the equipment). David Van Tieghem has provided original music and a sound design that amp up the effort and the impacts; at one point, a march feeds in, plus some Beethovenian heroics.

The circus, however, is also a competition-less sports event—one in which nine company stalwarts and seven additional performers steady or counterbalance equipment for one another. When Jackie Carlson and John Kasten perform on single large rings, colleagues haul on ropes attached to the pair’s “jerk vests” to make them swing through the air. In “Ascension,” when a long ladder anchored to the middle tower of a bridge structure rotates like a propeller, there’s always one person at the center of the bridge to control the balance as people climb one side and shift position as that side passes the top and starts down.

Act follows act in this bright, immaculate industrial playground. Equipment called “Air Rams” look like large hinges or accelerator pedals. A performer stepping on one is instantly catapulted up and forward by 30 pounds per square inch of pressure from tanks of air. The final section, “Kiss the Water,” involves Leonardo Giron Torres and Daniel Rysak on bungee cords above a shallow pool of water, springing, inverting in the air, flying outward (“I’m Superman!” “I’m Tinker Bell!”), and kicking the water, while others do belly flops and back flips (spectators in the front rows have been given rain ponchos). There’s even a non-human act in which red globes the size and heft of bowling balls are released to fall into clear plastic boxes (we hear the shatter of glass and, in the video projections, see brief flame-ups).

Streb’s imaginative ideas, the performers’ tremendous physical skills, and the potential danger that lurks in Kiss the Air! thrill the audience, although the very scale of the piece has a distancing effect despite all efforts to create an informal atmosphere. I wanted to be helped to know the performers better and be able to cheer each individual silently, the way you can in performances at Streb’s own SLAM in Brooklyn (There goes Fabio Tavares Silva (Associate Artistic Director); wow! Brava, Cassandra Joseph! You aced it, Giron Torres!, Carlson, Kasten, Rysak—terrific! Sarah Callan, Felix Hess, Samantha Jakus, yes!)

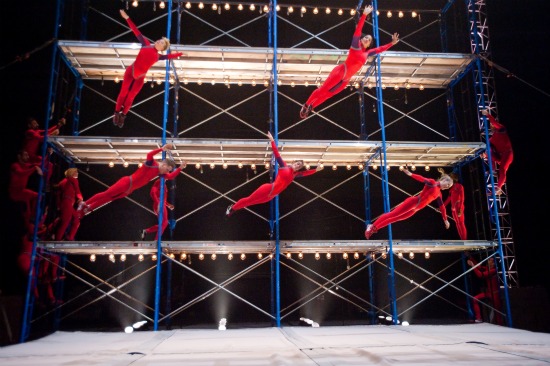

For me “Human Fountain” is the high point of the entertainment and the most resonant event of the evening. The three-tiered structure at the south end of the Armory is strung with lights. Performers climb onto its corridors mostly via the ladders at either end. Streb builds the excitement and degree of difficulty gradually. Basically the act is the same: step to the edge of the tier, dive out into the air, hit the mattress, and scramble out of the way of other fallers. Sometimes people twist in the air. It doesn’t take long to realize that the dancers in one tier can’t see those on other tiers when they launch—only after they’re airborne.

Suddenly timing equates survival. From higher and higher and in more rapid succession they fall. When you see Tavares Silva and Joseph poised at the top, you hold your breath; and it seems to take them forever to hit the ground. Then come diagonal dives that cross in the air, and, finally, the terrifying climax. Two on the top floor, three in the middle, four on the bottom all jump at once and land prone, arms spread, in a perfect formation, equally spaced out on the mattress. Disturbing memories of 9/11 mix with iconographic images of angels and here-and-now visions of champions. You could cry with admiration and relief.

LAVA’s Atlas by the company’s founder-director, Sarah East Johnson, reminds me a little of some of Streb’s early pieces, but that’s probably because of the aerial work and the emphasis on strength and timing. The two women’s aesthetic is very different, and Atlas, performed in the intimate space of Dixon Place December 1 through 11, explores navigational principles, topography, and natural phenomena with oddball charm and wit. It begins with a film of bare feet walking carefully across rocky terrain and sand to reach the sea, the camera advancing and backing away as the waves roll in and out. The walker is clearly the one holding the camera, not sure she wants to get too wet.

LAVA is a confederacy of strong women, and Atlas employs them in a string of brief acts, beginning with some neatly organized, rough-edged, modestly acrobatic dancing for Calia Marshall, Sarah Day Hirshan, Rose Calucchia, and Molly Chanoff that entails fingers pointing in different directions, as if to alert us to perspectives we may gain. For this number, the women wear white sleeveless tops and knee-length white pants with earth tones at the hem (costumes by Jocelyn Davis). Alison May’s lighting on the white floor and wall makes the modest space luminous.

Often, several things occur at once to spark an image. Three of the women roll slowly back and forth across the floor, while Allison Schnur climbs a fat white rope at the back and hangs from a loosely strung horizontal one by her hands or feet, or uses it as a hammock. At the same time, Mamie Minch sings words like, “You are the sea. . .” and “I built this ship; it listens to me.” It’s not surprising to hear what sounds like a foghorn. While Marshall and Hirshan, now wearing shimmery gold outfits, perform a gentle acrobatic duet on a trapeze, they sing to each other—at first slowly. The tune? Elton John’s “Rocket Man.” Meanwhile, beneath them, travelers pass: Lollo Romanski on roller skates, Diana Y Greiner on a scooter, Chanoff on a bike. As the song picks up speed, the voyagers double up: two on the bike, two on the scooter, Johnson hitching a ride on Romanski. Later in Atlas, while Johnson and Chanoff, do some expert tricky stuff together on a trapeze very close to the first row, they sing Roly Salley’s “Killing the Blues” in a cappella harmony.

This is a piece in which one feat consists of Johnson running in circles around the space, eyes focused straight ahead, and repeatedly managing to change her path to jump over a silver X in the center of the floor without ever looking down.

Along with sprucely-managed stunts like pyramids and vaults and catches involving a low trampoline, there are some beautiful sequences: Chanoff stands calmly on Johnson, Colucchia, and Romanski, while they roll smoothly over one another, and Minch, accompanying herself on an electric guitar, sings “The longest train I ever did see. . . .” There are also some telling jokes about spatial orientation and mass in relation to effort. In one brief scene, Schnur turns the real wall into her floor, using Romanski’s bent-over back as a support. In another, Romanski “rides” a stationary bike, pedaling away while Greiner and Schnur shove the thing across the stage. Later, she makes the trip again; this time Marshall straddles her shoulders and Hirshan perches on the handlebars. Now the two “pushers” have a very hard time moving the bike. Talk about an uphill journey.

Atlas‘s lovely finale takes place amid about 14 glowing little lamps that are let down on slim cords to hang amid the performers, who run and dance and lift one another and walk on their hands. When the lights are set swinging, the women have to dodge and duck. In the end, they’re all lying on their backs watching the tiny glowing objects move above them.

“A sweet show,” said a friend, by no means minimizing the rigor of the work. I’d second that.

I love the word “Beethovian”.

The last time I saw Streb’s work was outdoors here in Portland, Oregon, in Pioneer Square, a rather flamboyant space in the middle of downtown, where those flying bodies seen at dusk looked quite beautiful for the first five minutes or so. But I found that repeated wince-making body slams were all too resonant of physical pain, not the way I like to spend an evening. So Johnson’s “Lava” as so lovingly described is the work I would choose to see, preferring wit and charm to slam and bang in an era in which bombardment and assault seem to come from all four corners of the world on every level.