The star of Gideon Obarzanek’s Connected isn’t someone whose autograph you’d ask for, nor would you wish he/she/it would friend you on Facebook. The most compelling presence onstage during Chunky Move’s early November season at the Joyce was a kinetic sculpture designed by California artist Reuben Margolin.

Obarzanek, the director and choreographer of the Melbourne-based company, has always been interested in the interactions between dance, the visual arts, and media. His wonderful 2003 Tense Dave (co-choreographed with Lucy Guerin) took place in a revolving, circular “house” with pie-shaped rooms, and his endearingly rambunctious male piece, I Want to Dance Better at Parties (2004), involved film. More recently, with Glow (2006) and Mortal Engine (2008), he delved into digitized manipulations of light and imagery. His collaboration with Margolin involves artful, pre-digital mechanics and the harnessing of human power to control machines.

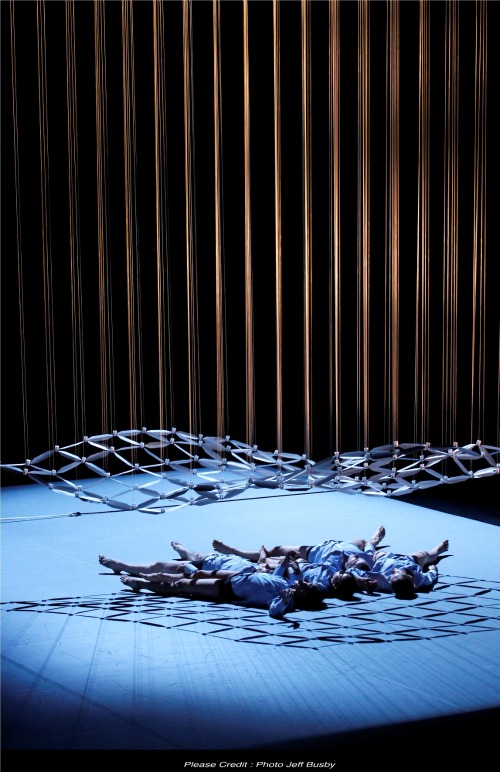

The above photograph will give you an idea of Margolin’s creation, although when seen from a seat in the theater, there’s more space between the suspended part of it and the vertical, loom-like structure and wheel that stand upstage right. At first sight, all that seems to be hanging from the overhead grid are a diagonal row of white strings, with small white objects attached to their ends. But while the dancers—Harriet Ritchie, gradually joined by Marnie Palomares, Sara Black, and Joseph Simons— are running and falling and rolling and hurling themselves into big loose jumps, Ross McCormack starts tinkering with the ends of the strings. As matter-of-factly precise as the others are impulsive, he inserts into pairs of the hanging sockets what turn out to be lengths of white paper folded in half vertically.

The powerful and many-voiced electronic score by Oren Ambarchi and Robin Fox creates an aural environment with big, dissonant clusters of tones, and Benjamin Cisterne’s lighting echoes the come-and-go shapes of the sculpture as other dancers help complete the design. Watching them, you may think that there seem to be more pieces of paper than the hanging strings need. Then—oh, marvelous!— the wheel turns, pulling some of the strings attached to it, and the sculpture rises and spreads into a canopy of white open-centered squares. A star is born.

Splendidly limber and passionate though the dancers are, it’s often hard to watch their activities when Margolin’s sculpture is such a vivid, moving presence. One of the closest interactions between it and the five dancers comes when four of them are attached in several places to strings that have been lying on the floor near the “loom.” Leaning or gesturing or stepping out, they cause the string and paper structure to tilt, billow, crumple, and spread out. The whole grid descends over Palomares like a magic garment that’s about to become her cloak.

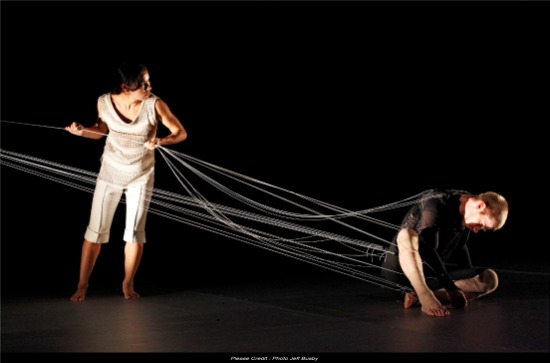

The most arresting passage occurs when only McCormack is attached; the small movements of his arms and legs induce a subtler dance in his inanimate partner. The puppet as puppeteer. It’s also fascinating to see Palomares pull strings that affect McCormack, and when the two engage in a duet, tangling carefully on the floor, the sculpture, in its own way, echoes their embraces.

During the last part of the work, the dancers exchange their attractive black or white outfits by Anna Cordingley for business suits, Now the mechanic (Brent Forsstrom-Jones, I assume) sets the wheel turning automatically and the sculpture keeps dancing, while the performers march around forming patterns that allude to Margolin’s design, and we hear the voices of what seem to be museum guards recounting tales from their daily work. As the fragmentary stories keep coming, the performers eventually discard everything but their white shirts, underwear, and gray socks in order to horse around. In the end, they lie supine, reaching up as the grid lowers toward them.

Obarzanek, I believe, had to begin working on the dance with Chunky Movers before the sculpture arrived in Melbourne. Maybe that’s why the choreography for the opening seems unrelated either to it or to the later intriguing and thought-provoking interactions between it and the cast. On the other hand, you could see the beginning of Connected as an allusion to the real beginning of the working process—dancers throwing themselves into their daily bouts, while others get their new fellow performer set up.

Sincerely enjoyed this review, Deborah. The Pillow and MASS MoCA are co-presenting this work in March, so your thoughts and observations have now excited and intrigued me even more!