What’s not to love about Fall for Dance? For $10, you can sit in the pseudo-Moorish splendor of the refurbished City Center Theater and view one of the mixed bills running through November 6. Now’s the time to revisit companies you admire and discover ones you’ve never heard of. And don’t hurry home. Hang out for a while in the atrium running between 55th and 56th Streets that has been transformed into Lounge FFD—a place to drink, snack, and talk with others about what you’ve just seen.

It helps if the weather isn’t unseasonably cold, as it was on October 25, the festival’s opening night (now that the theater’s stunning renovation has been completed, perhaps next year’s FFD can again begin in late September). Still, there was plenty to chat about, and for some people, arguing about dance heats one up amazingly well.

You can always debate Mark Morris’s 2003 gripping All Fours—not exactly a snappy opener and fascinatingly enigmatic. Béla Bartók’s String Quartet No. 4—played live by Jesse Mills and Georgy Valtchev (violins), Jessica Troy (viola), and Wolfram Koessel (cello)— rasps and buzzes and stumbles and sings out in thrilling dissonances, sounding at times like a Hungarian folk dance tune that’s had too much to drink (don’t, please, examine this metaphor too closely). In their wonderful, quick-footed duet, Aaron Loux and Dallas McMurray reel about the stage, propelled by the music and maintaining, wonderfully, their threatened equilibrium.

Morris plays with foursomes in his own way—multiplied into an octet, divided into duets. As for another possible reading of the title, you might see a few moves as doggy. Nicole Pearce’s lighting and Martin Pakledinaz’s dark, long-sleeved costumes help us to see the eight dancers in the opening allegro as anything but gay of heart. Sometimes the backdrop is midnight blue, more often a glowing red-orange. One of the group’s stopping poses is a proper ballet one, but in between such pauses, they swing ramrod limbs, pace with hands clasped behind their backs or lifted overhead as in extravagant prayer. Tiptoeing bent over, arms spread, they seem more like goblins than angels.

Loux, McMurray, Michelle Yard, and Rita Donohue are dressed in white—altogether sweeter and gentler together in the “Non troppo lento” movement of the music. But a mystery lurks here too. Toward the end of the men’s duet that precedes this, two of the black-clad men rush in, carry Loux and McMurray in identical, doll-stiff poses; set them down in a different spot; and speed away.

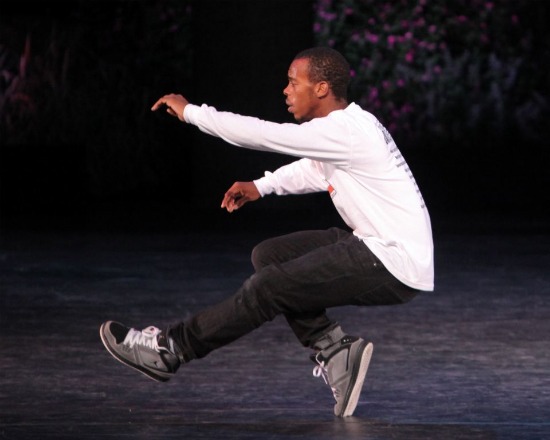

Lil Buck’s solo, The Swan, also gifts us with live music. Joshua Roman (cello) and Riza Hequibal Printup (harp) are seated onstage to play Camille Saint-Saëns’s familiar piece. If you haven’t seen the familiar Dying Swan of ballet reimagined by this master of Memphis Jookin,’ you can’t imagine how a rippling arm can as miraculously resemble water on a breeze-stirred lake as it can seem a wing. Lil Buck’s feet glide and twist in juicily controlled ways that make the stage floor appear to be a whole different, much slipperier surface. Swiveling, he often spirals up onto the toes of his sneakers. His limber body twists and bends to accommodate his remarkable footwork. Serious of mien, he ends on the floor in a knot (and receives a well-deserved standing ovation).

The quiet heart of the evening was Rogues, choreographed by Trisha Brown; set to spare, resonant music by Alvin Curran; and lit subtly by John Torres. The piece is a duet for company member Neal Beasley and Australian dancer-choreographer, Lee Serle, who has been working with Brown for the past year under the Rolex Mentor and Protegée Arts Initiative. The two men dance side by side, both literally and figuratively, throughout Rogues. Brown must have been entranced by the look of them together—Serle a lean 6’3” and Beasley much shorter and sturdier.

If they’re rogues, they keep that under wraps. They move calmly and deliberately—positioning an arm here, swinging a leg there, lunging, leaning, revolving, dropping to the floor. They travel a little to one side of the stage and back. They get faster. Curran’s music underscores their doings by sounds as varied as a balloon being rubbed (maybe), piano notes, a high sustained tone, and a pennywhistle and a harmonica getting friendly.

The men work mostly in unison—making us imagine this pensive dancing as an exacting, companionable form of labor. Frequently one of them falls less than a second behind the other and then catches up. The effect is striking—something between a fractional dissent about tempo and a full-fledged canon.

In October, Brown was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the annual “Bessies” (New York Dance and Performance Awards). On November 2, she received the Dorothy and Lilian Gish Prize, which brings with it an amazingly generous amount of money (approximately $300,000). The latter award defined the winners over its 18-year history as artists who have made an “outstanding contribution to the beauty of the world and to mankind’s enjoyment and understanding of life.” Yes.

Fall for Dance’s two opening programs ended with Joffrey Ballet’s performance of Edwaard Liang’s Woven Dreams. During its years in New York (1956-1994) as the city’s spunky downtown ballet company, the Joffrey’s repertory featured notable revivals of early 20th-century ballets (such as Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer’s reconstruction of Vaslav Nijisnky’s 1913 Rite of Spring), an occasional work by Robert Joffrey himself, ballets by its principal choreographer, Gerald Arpino, and (in the 1970s) pieces by an up-and-comer named Twyla Tharp.

Joffrey is long dead, Arpino passed away in 2008. The repertory of the company—now based in Chicago and led by Ashley C. Wheater—consists in part of ballets by current “in” choreographers: William Forsythe, Christopher Wheeldon, Wayne McGregor, et al. Jerome Robbins’s In the Night is performed, and Joffrey’s The Nutcracker brings in holiday crowds.

Given that showcasing rising talent is built into the company’s genes, it’s not surprising that the Joffrey has commissioned two works by Edwaard Liang, formerly a dancer with the New York City Ballet and Netherlands Dance Theater. Since he began choreographing in 2004, Liang has been in demand by a number of companies. So, yes, he has talent.

Although Woven Dreams was warmly received in Chicago when it premiered last May, it gave the disappointing impression at FFT that Liang had aimed for more than he could pull off with distinction. Not many old-pro choreographers would commit themselves to a six-movement ballet, set to music by four dissimilar composers (Maurice Ravel, Michael Galasso, Benjamin Britten, and Henryk Gorecki). The stated theme is a search to find a common thread through disparate nighttime visions, which gives a dancemaker a lot of leeway. But if this ballet represents Liang’s visions, I’d guess he spends his nights dreaming of endless ballets. Lines and circles and phalanxes of dancers (all wearing sleek, glistening blue costumes by Jeff Bauer) swoop into patterns. (There are some attractive passages of this sort in the first movement, but little that is profoundly imaginative enough to sustain the work as a whole.) Bauer’s immense web of fabric strips, dramatically lit by Jack Mehler descends and rises periodically to remind us of Liang’s theme, although the choreography doesn’t explore its possibilities.

Two pas de deux featuring Victoria Jaiani and Fabrice Calmels belong to the popular class of duets in which the man spends most of his time manipulating his partner—turning her, lifting her overhead, slinging her around his body. As we were leaving the theater after Woven Dreams, one dancer-choreographer in the audience mentioned being appalled by the prevalence of vaginas (covered, of course) being displayed to us. That happens in a lot of modern ballets; perhaps inured to it, people rarely see the image as coarse, and out of place in what seems meant to be a lyrical love duet.

It occurs to me, however, that one reason crotches stand out in Woven Dreams has to do with the cast’s performing. The Joffrey company has always been known for its spirit and onstage energy. I suppose it could have been first-night nerves that made the technically gifted dancers look so uninvested in what they were doing. Throughout Liang’s ballet, they performed as though they were still in the rehearsal studio, working to get every move correct. The men handled the women the way they might handle large, irregularly shaped packages; the women looked helpfully dependent. All 18 dancers followed the music, without revealing that it had any impact on their feelings.

Thanks, again, for your informative and constructive review of the opening Fall For Dance program. My first performance as a professional dancer was at City Center in 1960 in John Butler’s Carmina Burana. I wonder if the recent renovations included the backstage areas. I well remember running off stage into the wall.

Robert Joffrey was such a unique individual and artistic director that I would be very surprised to see the company, today,upholding his high standards. An impossible act to follow?

I remember Carmina Burana, especially the beautiful Carmen de Lavallade and Glen Tetley, That may have been the first time that I heard Carl Orff’s music. At that point in my life, reading Helen Waddell’s The Wandering Scholars, I was transfixed by the poetry of what had been dismissed as the Dark Ages in my high school history classes.

A note, by the way, to you and all my readers. The version of my Fall for Dance review I posted around 5:00 PM contained several glitches. It has been corrected and updated.

I must have seen Richard Gibson dance in Carmina Burana at City Center, truly memorable for all kinds of reasons including and especially Carmen de Lavallade, the girl in the Red Tunic. I was sitting in the front row of the second balcony with two friends who worked at the United Nations, one of them a Frenchwoman with vertigo, who kept leaning over the balcony and feeling dizzy, and was shocked, shocked, by the lasciviousness she was seeing on stage. So much for French sensuality.

As for the revelation of crotches…that seems to be a specialty of the Joffrey generally, or at least its former dancers who became choreographers, e.g. James Canfield who directed Oregon Ballet Theatre for some years and made many, many ballets featuring one hell of a lot of second position lifts.

Wish I’d seen the Trisha Brown piece however–she has certainly made my life better over the years. Thanks Deborah again for putting me in that wonderfully bizarre theater with you.

Couldn’t agree with you more Deborah – love Fall for Dance, one of the best offerings in NYC.