In 1994, we were all younger. Yet in the photo accompanying the review I wrote that year of Necessary Weather, the luminous collaboration by Dana Reitz, Sara Rudner, and Jennifer Tipton, Reitz and Rudner look almost exactly the way they do performing the piece at the Baryshnikov Arts Center in late October, 2011. They wear the same white pants and flowing, diaphanous white shirts. Reitz’s hair is shorter now.

Of course, the women aren’t the same, nor am I. They’re not even the “same” women they were at the first revival of Necessary Weather (conceived and structured by Reitz) in 2010. The older we get, the longer our histories and the more porous our memories. I can also recall both women as they were in the 1970s: Rudner lusciously silky, occasionally tempestuous in Twyla Tharp’s dances and in her own work; Reitz—tall, serene, and contemplative— already committed to performing solos as structured improvisations. (I even remember Tipton, the brilliant lighting designer, as a gangling Juilliard dance student.)

On one hand, I’m not moved to compare these remarkable women with their younger selves; on the other, I see them as all the selves they have been and still are.

Tipton’s lighting —glowing and darkening, forming circles or rectangles on the floor—creates an exquisite and enigmatically changeable terrain. Whether her effects respond to the two performers or they to her is moot. When a large pool of light appears in the middle of the space, Reitz and Rudner sit opposite each other on its rim and gaze into it. Reitz gathers and molds space with fluid arm gestures (occasionally Rudner joins her in this, but with different shadings); at one point, a shaft of light invisible to us illumines their hands. When a large lamp casts a beam from one high corner, the performers respond to its presence the way one might search for the source of moonlight.

The dancing in Necessary Weather doesn’t involve high kicks or big jumps. Never has. The women are at home with gravity—treading smoothly, twisting and slipping through pockets of space. Reitz is like a heron at a pond’s edge, picking up a foot, cocking her head, adjusting her shoulders, conjuring with those sentient hands. Rudner seems more impulsive, occasionally erupting into scampy flurries of motion that make her gray-black curls fly. They are both profoundly aware of each other, the light, and the atmosphere of the room. In the silence that accompanies the dance, their every small gesture seems charged; we can detect nuances within a move as simple as the lift of an arm.

Thinking, making decisions, occasionally mischievous, the two go about their beautiful business in a composed, matter-of-fact way. The stage is their home, the light their inner kingdom. At one point, Reitz enters, almost silhouetted against an amber sky, bearing a straw hat. Rudner meets her in the center of the stage, and suddenly a pin-spot from overhead turns the inverted hat into a bowl of light that they hold between them. As if this were nothing extraordinary, the performers converse barely audibly, looking like neighbors who’ve met on a village street on their way to a potluck supper.

But of course, they’re not ordinary. Performers like these two are rare. Movements settle on them, tickle them, emanate from them, are born in them. I’m not diminishing Tipton’s contribution when I say that Reitz and Rudner carry their own kind of light.

It’s been years since Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion appeared in New York and won a 2004 Bessie (New York Dance and Performance Award) for their Both Sitting Duet. Ever since then, occasionally feeling gloomy during some performance or other, I’ve wished that a fed-up theater goblin would whisk away the show I’m watching and deposit Burrows and Fargion in its place.

Burrows is a choreographer who danced with Britain’s Royal Ballet for 13 years. Fargion is a composer who has collaborated with choreographers. But Burrows and Fargion together in any one of the duets they have created to date zip blithely across borders between the arts. Their Cheap Lecture and Cow Piece—two of the five works seen on their Danspace St. Mark’s programs November 3 through 5—could be class acts in a very brainy postmodern vaudeville.

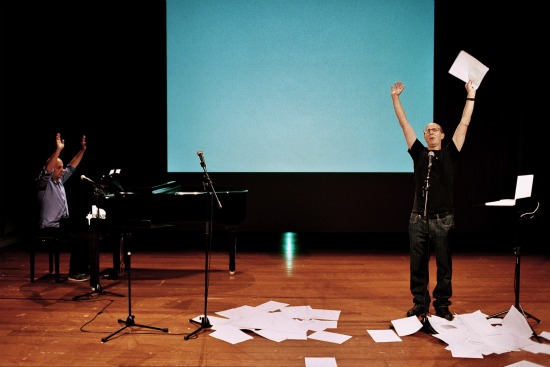

Burrows and Fargion do not, you know. . .dance. Wait, I take that back. To begin with, Burrows really does dance—casually delivering some smart little steps in one spot in Cow Piece. But more importantly, the two create a bewitchingly witty dance of words and music and props. In Cheap Lecture, they perform quite close to the audience behind two music stands and in front of a large white screen. They hold sheaves of paper containing their text and cues; once done with a sheet, they toss it to the floor the way radio actors do. The papers’ dance is the unruliest element, and it’s not all that unruly.

The men admit during the performance that they were gobsmacked by John Cage’s Lecture on Nothing and borrowed its structure. This means that—according to some carefully timed structure related to the music that we hear intermittently on tape—they may deliver, (alone, in unison, or in counterpoint) a lot of text very, very fast, or slow sentences down to fit an allotted time. Frequently, the speaker inserts a pause between words that normally follow each other smoothly, or puts a pause between syllables—which has a very strange effect, as if his brain had gone dead for a second. (If Cage, Gertrude Stein, and W.S. Gilbert had had a child together. . . Impossible, but you get my drift.) Certain of the spoken words are projected on the screen—sometimes just one, sometimes many. When the performers speak of visual and aural rhythms, we understand their point.

Burrows and Fargion are brisk cheery fellows—grin a lot, break up sometimes, never let the pace drop or the rhythms falter (not unintentionally anyway). They speak of many things, uttering pronouncements like “Some things made with ease don’t come easily” and “We don’t know what we’re doing but we’re doing it.” And of course, this exacting work didn’t come easily, nor do they not know very well what they’re doing.

Their ideas can be provocative. The music is defined as “a wall of rhythms against which our thoughts can lean.” But like good stand-up comedians, they know how to include us in their game and throw out asides. They’re also informative. Burrows counts numerical sequences for us. We learn that their Cheap Lecture relates to Cage’s Lecture on Nothing the way that composer’s Cheap Imitation relates to Eric Satie’s Socrate (which the Satie estate would not allow Merce Cunningham to use for his already-created dance, Second Hand).

And how did Schubert get in here? Schubert with his “fat, stubby hands?” Isn’t that his melody that Fargion goes to the piano to play near the end of Cheap Lecture? What about those hymn-like chords that the taped score keeps intoning? From left field, pleasures keep zinging in. After saying he wants to be a dancing man, also to leave his footprints in the sand, Burrows keeps throwing up his arms, yelling “Cossack! and Yeaah!” in various combinations and with various pauses—tickled to be doing so. The end.

Only it isn’t, because Cow Piece begins immediately. The cows have been there all along: three small plastic Holsteins and three Ayrshires lined up on each of two tables. Burrows has his herd, Fargion his. Both men also have notebooks to consult and musical instruments to play: mandolin; accordion; harmonica; small, table-top harmonium; and a soda can hit with a stick. Two songs advertise the collaborators’ respective patrimonies. Fargion, born in Milan, sings a Neapolitan love song in English; Burrows comes up with a British music-hall ditty, “Your Baby Has Gone Down the Plughole.”

It’s probably too soon to put forth love and death as a theme in the deliriously, mind-bogglingly eccentric Cow Piece, but keep it in the back of your mind. Burrows and Fargion handle their cows rhythmically, decisively, and often violently. Each has his own method. They may segregate them as to black-and-white and brown-and-white, lay them on their sides, slap them down rapidly like cards in a cut-throat play-off, or change the animals’ placing as if trying to deceive us with a shell game. Fargion holds two of them up by his ears and shakes them like maracas.

I would not like to be one of those cows. Burrows nestles his on a scarf, then tumbles down, taking the herd with him. Fargion has a supply of tiny nooses; he can loop one around a cow’s neck before throwing it to the floor. Toward the end, two cows are perched at the very edge of the table, and Fargion, speaking for them in a falsetto, cries out for help ( “Aiuto!”), before shoving them off and starting to sing—also in a high, frail voice—the lament Henry Purcell wrote for his Dido (“When I am laid in earth. . .”).

What did I tell you about love and death? Burrows actually says those words at one fast-paced point. Then there’s the dialogue that Fargion conducts in two voices between death and an unwilling victim; it sounds like a clumsy translation of the Schubert lieder “Death and the Maiden” (sample: “Go away, you fierce skeleton!”). To a foot-tappingly jaunty tune, the men tell us “Don’t fear the reaper.” Oh, right. We saw how you two toyed with those cows. We’re ready to be very afraid. As soon as we stop laughing.