Since Laura Peterson began to show her choreography in New York around six years ago, she has become increasingly interested in transforming theater spaces through lighting, audience placement, and movement ideas. I’m thinking in particular of her 2007 I Love Dan Flavin, which I saw in the funky, cramped intimacy of the old Dixon Place, and Forever (2009), which utilized the columns and mirrored wall of Dance New Amsterdam.

Between November 4 and 12, her new Wooden transformed HERE in more ambitious ways. And though, like all Peterson’s pieces so far, it doesn’t tell stories, it obliquely conveys a message about growth and decay, and—even more subtly— hints at the world’s-end scenario that our despoiling of the planet’s resources may bring about.

I was unable to see the first brief segment of Wooden, performed while the audience was entering the theater by a guest soloist (different ones at each show) in the “hallway” fabricated by a curtain. The first group of audience members turned a corner after going through the door into the theater and stopped there, watching Asmina Chremos do whatever she did. By the time I got into the hall, Chremos was leaving it.

Almost the first thing you notice upon reaching the performance space and finding a seat on wooden park benches is the smell. It’s emanating from the turf in front of us that almost fills the shallow space. This is living grass that needs watering and mowing. On the last night of Wooden, a few patches along the edges have given up, but the rest glows green when Amanda K. Ringger’s early morning light slants across it. The dancers’ feet sink into it.

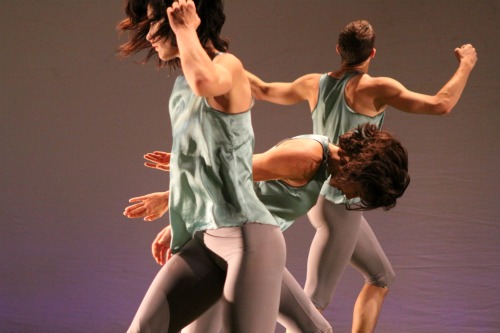

The first few minutes of the piece are the most compelling. The four performers (Peterson, Kate Martel, Edward Rice, and Janna Diamond) are scattered across the lawn. A loud hum in Soichiro Migita’s sound design surrounds them. They’re wearing greyish tights cut off at the knee and loose, pale blue silk tunics (costumes by Candice Thompson), and they’re all immobile in a curiously strained position. You might assume it if you were pretending to be a seal. Facing the floor, with their weight braced on their hands and thighs, they could be partway into a modified push-up, but their heads are hanging, and you can imagine the stress their shoulders are experiencing. Via a series of blackouts, they reappear in different spots on the grass; occasionally one of them will be caught looking at the others, but otherwise the position remains the same.

It’s as if someone has set up a time-lapse camera, but sequenced the shots it takes too far apart to render flow. As you watch this repeated stop-action, the pose seems odder and odder. What were/are these people doing? What will they do?

Iteration of one kind or another is crucial to Peterson’s choreography. Over and over, the performers lunge deeply to the side, turn, sit, roll, and rise—all in one smooth action. At this point in the dance, every small deviation or variation seems notable. Ringger’s light monitors the passage of a day, coloring the backcloth, dappling the grass. The background is green when the dancers cluster, lean together, and branch their straight arms out in all directions. The only anomaly is all this curiousness is a solo for Rice that looks unexpectedly like something you might do in a fairly adventurous dance class.

For the rest of Wooden’s first half, the dancers roll, run, and hurtle back and forth across the space on individual tracks. Sometimes they labor to travel in one direction and are blown back. They appear increasingly disoriented, seem to struggle for control. Time stands still, and my concentration wanes. By the end, they’re able to return their original poses.

The two halves of Wooden are separated by an intermission, and by the time we return to the performing space, it has become a drier, browner, more desolate environment. Our benches have been moved onto the grass, and we sit facing the opposite direction. The branches (stripped of their bark) that have been suspended around the spectators all along become more prominent (and ominous), as do the room’s columns, wrapped in gray paper. In this desert, Martel and Rice, now wearing beige tights and sleeveless tops, dance with their backs to us. The sounds that have been relatively benign become grating, terrible, murderous. The two walk away, twisting and jerking, twitching their shoulders. They lean together, braced in a shoulder lock. No branching arms now.

The music has quieted down by the time Diamond and Peterson arrive against the white-lit backcloth; the electronic sounds resemble the amplified rustle of leaves and the snap of a twig. The dancing is very precisely designed. Peterson’s style, which in the past has often enhanced her wit and comedic sense, has never been what I’d call voluptuous; it has an ungainly allure, with more straight or angled lines than curved ones. She herself (an intriguing performer) can dance like a wild, but tensed-up child, flesh pared down to bone. In her arresting solo in this part of Wooden, she looks at times almost—but not—robotic, numbed by something beyond her control.

Clear though the dancers’ movements are, they also convey stress. The four fall to their knees, get up and do it again. They bounce stiffly, run bent over. The sky reddens. Martel sets the branches swinging over the other three as they lie prone on the ground. By the end, she and Rice are back in their original positions, and the light seems to take forever to go out.

Part installation, part dance, Wooden doesn’t always make its import sink in deeply, but most of the time, it makes you want to keep watching. And thinking.