William Forsythe is an innovator. I doubt that fact is even up for debate among those who adore his work, those who loathe it, and those who simply scratch their heads over it. His post post-Balanchine ballets, his installations, his recent theater pieces, and his 2004 computer app, Improvisation Technologies: A Tool for the Analytical Dance Eye, have influenced choreographers, performers, teachers, and thinkers outside the dance world.

Scholars in Europe and the American continent chew over his work in the light of the ideas he has articulated. Take this sentence by Sabine Huschka (referencing an earlier text of hers in a 2010 essay in Dance Research Journal titled “Media-Bodies: Choreography as Intermedial Thinking Through in the Work of William Forsythe”): “So, performative sequences of choreographed movement fold projected, imagined, constructed, and physically remembered images of the body into processes of generating and forming movement-actions.”

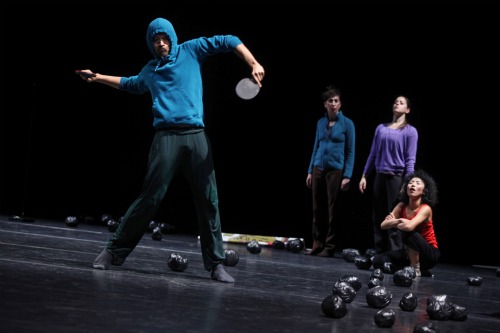

Umm, yes. That is, yes as far as dance studies go. And yes as an allusion to the processes that dancers and choreographers can deal with. But I don’t think that all the spectators who attend performances of Forsythe’s work and cheer for them see what Huschka is talking about. Watching his 2008 I don’t believe in outer space, presented by The Forsythe Company at the Brooklyn Academy of Music October 26 through 29, you may decide that the medium-sized, irregularly-shaped, slightly shiny balls littering the stage represent fallen meteorites, and go on to link them with the title. But unless you’ve read everything written about Forsythe, you may not know that he and his dancers collected the wadded-up balls of tape that stagehands form when they rip apart the floor-covering that the company tours with. Why did the company amass these? They might come in handy some day.

You also might not know that in 2008, Forsythe was looking ahead to his 60th birthday; it was therefore an especially fortuitous time for him to delve into the body’s memories, desires, and anticipated events. I don’t believe in outer space can be considered an eccentric road map of his memories and those of his highly collaborative dancers. In any case, you simply take in and relish (or not) the many isolated, often absurd events powered by movement, text, lighting, and sounds. This is the first work of Forsythe’s that has made me think of Pina Bausch— except that repetition is a crucial part of her collages of vignettes, which are organized in a tidy way for maximum theatricality. Forsythe doesn’t seem to think in terms of sewing things up.

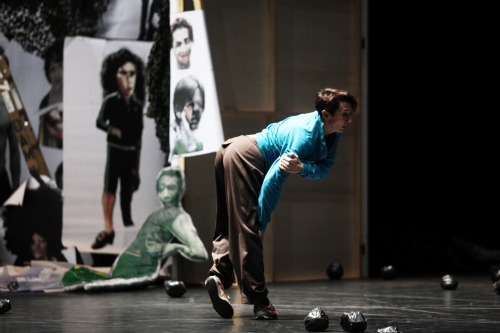

I don’t believe in outer space strikes me as less impressive and thought-provoking than his Three Atmospheric Studies and Decreation(both shown at BAM in the past decade). He has described the piece as “a series of preposterous takes on the theme of giving it up.” That idea—along with the urge to survive—doesn’t shine out clearly or provide the strong glue that the themes of those other works did. Nor is the space as well defined by zones of activity or objects. To the audience’s left is what looks somewhat like the interior of very messy office (I’m not sure that spectators seated on the far left of the theater can see into it). Cast members sometimes retreat into it. Papered with photos—torn, hanging loose, crumpled on the floor—it hints at the mental scrapbook that the whole piece seems to be.

The stage is a bleak place. Thom Willems’s score may suddenly blare (sound design by Niels Lanz) and the lights (by Tanja Rühl and Ulf Naumann) blaze and just as swiftly darken. Once, one of the performers (Katja Cheraneva) screams, and everything halts. People wander in and out of the space; suddenly they’re just there, as if they’d been poured in by a wily scientist to see how they might affect the existing population. The dancing—for instance, an intriguing solo by Esther Balfe, and another, quieter, equally impressive one by Yasutake Shimaji—is echt Forsythe. The performers’ bodies seem to be imprinted with fragmentary ideas that twitch, roll, and wriggle their way through muscles and nerves—constantly diverted to new paths and both fascinating and disturbing to watch.

As usual, the performers (17 of them) are magnificently daring and wonderfully expressive. When the piece begins, two men are grappling at the back of the stage, as if they’re stuck together and not entirely liking that condition. Tilman O’Donnell lies supine, occasionally talking into an empty paper towel tube. When Josh Johnson arrives dancing, he has some of the tape balls stuffed into his pants and shirt to simulate protuberant buttocks and breasts. But it’s almost impossible to keep your eyes off the stellar Dana Caspersen, who has worked with Forsythe since 1988. She’s channeling two people who are having an increasingly peculiar conversation about mundane matters. In a high nervous voice, she welcomes a newcomer to the neighborhood, then spraddles her legs and bends her knees deeply to dredge out of her guts the hoarse, snarling voice of the visitor. He or she may admit to living just down the block, but whoever said Death always told the truth?

Amancio Gonzalez appears beside Caspersen, lip synching (I believe) her words. It’s a device Forsythe uses throughout the piece. The performers often move their mouths to form sentences we may or may not hear, and we can’t always tell who’s actually speaking.

Left to right: Fabrice Mazliah, Roberta Mosca, Ander Zabala, Elizabeth Waterhouse, Dana Caspersen. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Fairly early in I don’t believe in outer space, Casperson hints at its form. “As if by chance,” she confides, “there’s a lot of stuff all over the place, things moving in all kinds of different directions. . .” She wants us to know that—as if by chance, randomly—things separate, collide, stop. As in life. And, as in life, there are memorable moments in Forsythe’s piece. Shimaji, inscrutable in a hoodie, pantomimes a wacky ping-pong match with no ball or net. He wields two paddles; his opponent, Gonzalez, has none. Jone San Martin, Elizabeth Waterhouse, and Yoko Ando watch appreciatively, if not always accurately. Tilman, wearing a kneepad over his face, impersonates a professor; I think it’s he who remarks that there’s no research, only researchers, as he hastily stuffs tape balls under his sweat jacket. Once, while Caspersen talks, Ander Zabala unleashes his impressive singing voice. Another time, holding a mike on a long pole above her, he produces what he makes very clear are farts; Waterhouse, Roberta Mosca, and Fabrice Mazliah make terrible faces, as if these were daily exercises.

Forsythe’s title alludes to a sentence in “I Will Survive,” the song known best for Gloria Gaynor’s rendition of it. Caspersen delivers the crucial verse that begins “I will survive/ as long as I know how to love” in an anguished, terrified howl, as she backs away along the floor from a figure she sees as threatening. At the very end of I don’t believe in outer space, she lists all the things she’ll have to do without: “no more falling. . .no more having a beautiful blue dress and wearing it to the dance. . .no more saying ‘at first I was afraid.’” Those last words lead her into the song again: “and so you’re back/ from outer space,” she says. “I just walked in to find you here/ with that sad look on your face./ I should have changed my stupid lock. . . .” Meanwhile the curtain is falling. Very, very slowly.

Note to Forsythe: in December, you’ll turn 62. That’s not so bad, right? I thought so. You’re surviving nicely. And let’s hope you got the fear out of your system.

Hi Debbie: Reading about Forsythe, so richly described here, as well as seeing his work for so many years suggested some questions that may not have easy answers. How do choreographers fare without their own companies? Without specific financial advocates? How effective is our haphazard system of concerts and festivals? Are we losing some valuable choreographic voices with these arrangements? Or on the contrary are we getting as much as we need? All the best, gigi

I can only follow Forsythe’s work remotely, and in erratic samplings — your descriptions make me wish I got more chances at his repertory.