In successive October weeks, two ballet companies with very dissimilar identities and agendas appeared at the Joyce Theater. The Houston Ballet is composed of over 50 dancers. It also boasts a handsome, beyond-spacious new building in its hometown (price: a surprisingly modest $46,600,00) that’s connected by a bridge to the Wortham Theater Center, where the company and the Houston Grand Opera perform. Artistic director Stanton Welch balances the repertory (and, no doubt, the budget) by presenting both full-length ballets (such as his 2009 Marie and Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon) and shorter, edgier works.

The Suzanne Farrell Ballet was founded ten years ago as an outgrowth of the summer intensive ballet classes given at the Kennedy Center by Farrell—George Balanchine’s last, and perhaps greatest muse. The company has annual seasons in D.C., and it tours. It has remained, at least in part, a pick-up group, with regular members augmented by guest artists; Farrell isn’t very interested in new works; the company is a vital element in her mission to stage and coach Balanchine ballets—mainly those that were part of her repertory when she was a dazzling, musically sensitive young dancer—as well as remounting ones that haven’t been seen in years for her own and other institutions as part of her group’s Balanchine Preservation Initiative.

Because the Joyce’s medium-sized stage and lack of a pit militates against extravaganzas, or even ballets with large casts, the Houston Ballet arrived with three works—none of them requiring more than eight dancers—and double-cast two of them. The Joyce Foundation had awarded the company its first Rudolf Nureyev Prize for New Dance —a $25,000 grant to a ballet company wishing to commission a small-cast work; in other words, a work enabling said company to show its chops in a non-opera-house setting—say, at the Joyce. And the winner is. . .Jorma Elo! Elo’s One/end/One formed the centerpiece of the Houston Ballet’s Joyce program, bookended by Jirí Kylián’s 1989 Falling Angels and Christopher Bruce’s 2006 Hush.

The Houston company has skilled dancers—strong, well-trained, up for anything. And anything is what Elo demands. His ballets (what company doesn’t have an Elo these days?) embellish the classical vocabulary with little jolts and quirks that audiences find fascinating—electric, somehow. One/end/One pits four couples against Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 4 in D major (heard in a recording by the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra). The women wear handsome, gold-trimmed black tutus by Holly Hynes (their elegance somewhat sabotaged by the acreage of black panties they reveal); the men are costumed to match.

Elo’s choreography for One/end/One is meticulously on the music, but it doesn’t breathe with it. The dancers often resemble dolls, walking stiffly, cocking their heads. Sometimes they undulate while performing pointework. Picture a snake in a tutu. For dancers, doing Elo’s choreography must be like multi-tasking; head here, shoulder there, twitch this, roll that. This sprightly little ballet is rife with oddities. For instance, here’s a maneuver in the duet that’s excellently performed by Karina Gonzalez and Connor Walsh: Gonzalez strikes an arabesque; Walsh embraces her lifted leg as if it were a football he plans to run with, and turns her into position; then he releases his grip and with one hand traces several little circles in the air around her ankle. He also ends a sequence of supported cartwheels by burying his face in her net skirt. After that, he takes a short nap.

Perhaps coincidentally, all three ballets on Houston’s Joyce program involve a lot of quirky angularity and staccato moves. Falling Angels, created by Kylián for Netherlands Dance Theater (with which Elo performed in the 1990s), is set to Steve Reich’s Drumming. Kylián embraces Reich’s spartan power, creating a clever analogue to that compelling musical exercise, which starts out simple and accumulates complexity as instruments join and rhythmic patterns layer over one another, displacing accents. Finally, dancers and percussionists (heard on tape) work their way back to simplicity.

The eight women wear black leotards, white socks, and white jazz shoes. Each begins in her own rectangle of light. Despite occasional flirty glances or defiant stares at the audience, the women work their trim little butts off. The choreography allows individuals or pairs to emerge or swim against the current, but always within the confines of the pattern.

Bruce’s Hush, choreographed for the Houston Ballet in 2006, makes a different use of abruptness. A family of buskers, or maybe circus performers, enters in a procession; father, mother, and kids. Wearing Marian Bruce’s attractively ragtag clothes, they jerk along, pausing occasionally like wind-up toys with iffy circuitry. But they’re camping here for the night, and Bruce’s musical choices—as varied as a Vivaldi adagio, the Bach-Gounod “Ave Maria,” Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Flight of the Bumblebee,” and a hoedown—suggest life as a series of numbers. On the other hand, all the selections are performed by Bobby McFerrin and Yo-Yo Ma, which gives them a bubbly, sometimes poignant charm. Hearing the tunes in the context of Bruce’s work, you can almost imagine the mechanical organ of a distant merry-go-round.

Hush is a modest little work, gratifyingly unaffected, and it shows off the dancers’ dramatic abilities as well as their technical skills. The mother (Kelly Myernick) checks on the sleeping children and does an abstracted version of housework. The elder brother (Rhodes Elliott) performs some very nice jumps, and his sibling (Ilya Kozadayev) picks up the steps. Even Dad (James Kotesky) joins in. He also dances fondly with the littlest girl (Melody Mennite), who has just bested her brothers by catching the flying insect they’re chasing, putting it in her mouth, spitting it out, and stamping on it. A sister (Jessica Collado) forms a trio with the boys. You see the parents’ affection for one another. In the end, crickets chirp, and the family members gather up their stuff and trudge on down the road.

The polished program at the Joyce wisely introduced the company to New York in the form of an amuse-bouche. It did its job: whetting our appetites for more glimpses of these dancers.

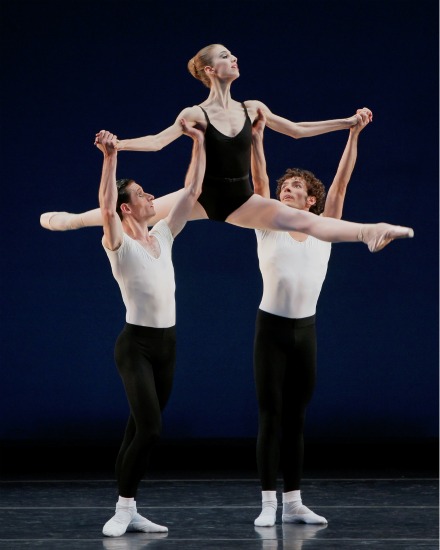

The Suzanne Farrell Ballet's Elisabeth Holowchuk and Kirk Henning in Balanchine's Haieff Divertimento. Photo: Carol Pratt

What ballet-lover doesn’t want to cheer Suzanne Farrell on? Her coaching of performers in the Balanchine repertory focuses on musicality and nuances within the overall shape of the choreography. Her company can make you discern details in Balanchine’s ballets that dancers in other companies—even those in the New York City Ballet—often glide past. The revelations she provides balance the problems her group faces. The dancers who performed during her company’s Joyce season are all very good, and some much better than that. They understand what Farrell is after, but they’re not uniformly brilliant, and that is disappointing. At times, you can almost feel her guiding hand still on them; I’m reminded of certain Russian dancers who perform as if they were hearing in their heads their coach’s dictates about each step.

The novelty of the Joyce program was Balanchine’s 1947 ballet, Haieff Divertimento, re-mounted by Todd Bolender for the Kansas City Ballet in 1985 and last seen here in a 1993 New York City Ballet reconstruction. Four couples and a lone man are onstage when the curtain opens and a trumpet call sounds in Alexei Haieff’s music. They look like a gathering of blue jays, thanks to Holly Hynes’s very attractive costumes (tunics for the women over long-sleeved leotards). Bluebirds, however, are not as good at symmetry or as polite as these partners, who bow to each other at every opportunity. The choreographic texture, interestingly, isn’t as dense as it is in many of Balanchine’s works—by which I mean that there appear to be fewer steps per musical phrase. The ballet’s opening section has the look of a very sleek, finely-wrought primer of classical moves. The single man in paler blue (Kurt Henning) behaves like a host, but also evokes the hero of many 19th-century ballets; “where is the one for me?” his gaze and gestures seem to say. Or “she was here just a minute ago. . . .”

The second section brings him the girl of his dreams (Elisabeth Holowchuk), who falls into his arms without hesitation. Their duet has a number of unusual moves. When the woman steps into an arabesque, confronting her partner and holding onto him, she paws the air with her lifted leg in an unusual, very beguiling way. Or, face to face, the two thrust straight arms past each other’s shoulders and alternately spread and close their fingers, somewhat the way the hero of Balanchine’s Apollo does.

The ballerina has a quiet solo (identified as “Lullabye” in the original production), as if she were out walking in a stylish but dreamy fashion, gazing around and up at the sky, perhaps dejected. At the end of the ballet, she leaves. However, this isn’t a sad work; there are smart, individual jumping passages for the four secondary men and solos for the women they brought to the party.

At this point, the dancing by the Suzanne Farrell Ballet seems brittle in places and not entirely in tune with Haieff’s effusive music. Nancy Reynolds’ Repertory in Review makes it clear that in 1947, both critics and the original dancers found the ballet light-hearted and charming, full of wit. Of course. The glamorous Mary Ellen Moylan was the ballerina and Francisco Moncion partnered her. The cast included Bolender and the young Tanaquil Le Clercq. Farrell’s dancers treat Haieff Divertimento with care and respect, as if afraid they might break it.

When Balanchine made Meditation in 1963 for Farrell and Jacques d’Amboise, she had been in the NYCB only two years, and the choreographer was crazy about her. A poet’s muse alludes to daffodils and sunrises (whatever turns her on) and issues orders: “Get to work. Write!” A choreographer’s muse offers her body as material. And the impact of this tall, slightly gangly, very musical teenager must have been overwhelming for Balanchine. When Holowchk enters and comes up behind the hero (Michael Cook) kneeling in despair, his hands over his eyes, she doesn’t just embrace him lightly; she wraps her arms around his head. He may be dreaming her, but she’s not an elusive sylph, she’s all his. For the moment. Holowchuk becomes bolder in this—extravagant, glamorous—and Cook is effectively ardent.

By 1967, Farrell was fully fledged. In making her the ballerina—again partnered by d’Amboise—in Diamonds, the finale of his Jewels, he installed her as a princess in the Russia of his youth, as well as the kind of magical female who inhabits such worlds as Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. In this excerpted pas de deux, the man (Cook again) looks at the woman (Violeta Angelova) as if he were saying over and over under his breath, “Oh, you marvelous creature!” while she sometimes gazes offstage as if into another domain.

It’s always painful to see a Balanchine ballet danced to taped music, especially when the volume level is too high, as it often is at the Joyce. And Agon, with its bristling Stravinsky score, may have a small cast, but it needs a lot of air around it. Again, Farrell’s dancers perform this great 1957 ballet with understanding and commitment, but not all of them with the spiky finesse it requires. Holowchuck and Momchil Mladenov danced very well together in the uncanny pas de deux that once featured Farrell (this time, the muse gets tested to the extent of her flexibility). Angelova in the second pas de trois looked strangely meek and underpowered the night I saw the company.

As I said before, admirers of Balanchine owe Farrell much. And perhaps it’s too unrealistic to hope that, in addition to staging his ballets for companies around the world, she can find whatever it takes in the way of time and money to maintain her own group at the highest professional level.

Ze’eva Cohen kindly forwarded your review of Huston Ballet and Suzanne Farrell Co.s and suggested that I request my being put on your mailing list. I have always enjoyed and trusted your writing and have missed reading it lately.I was in N.Y. For both of the above mentioned performances and found your comments both astute and constructive. I am afraid that my expectations were too high for Farrell’s Co. and found myself not only disappointed but embarrassed. If possible please add me to your mailing list With thanks in advance,

Richard Gibson

I am delighted to tell you, Deborah, and your readers, that Oregon Ballet Theatre does not, repeat does not, have a Jorma Elo ballet in their repertory and I hope they don’t acquire one. The comment about treating the dancers like dolls resonates, boy does it. That’s possibly an improvement over treating them like robots or machines of some kind, but my dislike of this choreographer’s work is based on his suppression of the human in the most human of the arts.

I have already commented elsewhere that I would love to see Balanchine’s Divertimento (Haieff) and I’m very pleased that you cited its revival by Todd Bolender for Kansas City Ballet in 1985. I’ve never seen the ballet, and your description, as well as Tobi’s, is very helpful. Beyond that, Gavin Larsen, who retired as a principal dancer from Oregon Ballet Theatre a couple of years ago, and danced for one season with the Farrell Ballet before she came here to Portland, told me that Farrell commissioned a modern piece from someone on the faculty at the school in Florida where she too is on the faculty (can’t remember which campus it is) and she, Gavin, got her first opportunity to dance barefoot. That’s a while ago; maybe she’ll try new work again.