Some choreographers devote a lot of creative energy to finding a great new way to lift a leg (or a partner), or maybe split unison into counterpoint. Wally Cardona and Jennifer Lacey? Not so much. Undertaking alone—he in New York, she in Paris — the research that led to their joint project, Tool Is Loot (at the Kitchen September 22 through 24 and September 29 through October 1), they sought advice and responses from people in other fields, including an astrophysicist, a sommelier, a medical supply salesman, and an opera singer. Each choreographer offered the chosen expert-of-the-moment an “empty solo,” onto which said expert could project his or her desires and instructions.

I saw Cardona perform one of these “interventions” at the Baryshnikov Arts Center last winter. He and sound artist-social activist Robert Sember worked together for a week and then showed the result, with Francis Stansky and Sember getting into the act. What followed was a pause-pocked interplay of verbal instructions and the movements they generated; we could see thoughtful, non sequitur gestures without knowing the instructions that produced them; see-hear the two strands together as cause and effect; and watch the men interpreting in their own ways what they heard through headphones The experience was curious, as if a game played with basic movements had become something knottier and wispier at the same time.

Cardona’s and Lacey’s initial projects, perhaps buckling under so much input, disappeared, but some of the ideas generated during the process found their way into the fascinating and mysterious Tool Is Loot. Here we see two vastly gifted dancers having their way—alone and together—with ideas thrust upon them. The invited dramaturges no longer have immediate power. For the pair’s Kitchen season, the collaborators are composer Jonathan Bepler and lighting designer Thomas Dunn, who offer their own rich forms of commentary and interpretation (Bepler’s score involves a variety of orchestral instruments, plus samplings—such as passages by a children’s choir and a Japanese recorder club.)

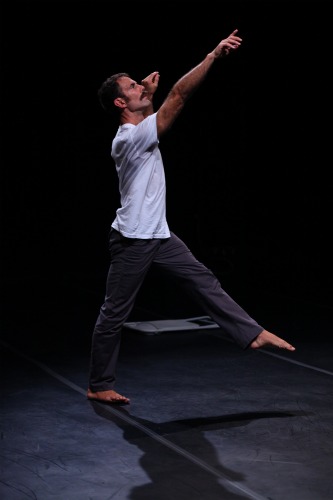

The delayed-meaning idea comes into play with Cardona’s first solo. You watch him and think, “What is this man doing?” Clearly something. Eyes closed, he listens; perhaps he’s in dark place. He walks on tiptoe, tracing scalloping paths. He gestures, seems to swoon in rapture, strikes a heroic pose, stumbles over a folding chair, humps it briefly, bows (not in that order). He slides his hand under his shirt and strokes himself, licks his armpit, moans a little. The solo is a marvel of unexpected movements and emotions vividly rendered. Drum beats. Exit.

Then we hear Lacey’s voice telling of an erotic encounter between a young prince and a mustachioed sailor (Cardona’s own mustache is impressive). Was their meeting planned? The prince slips out of the palace at night, a cloak is thrown over his head, he is pushed down. Hands move over his body; he faints. He wakes alone. So that is what Cardona’s solo was envisioning. And the tenderness of the sailor, the skipping young prince, the cloak over the face recur later, both in movement images and in a recorded voice (Cardona’s) that rises excitedly into a childish squeak.

One of Lacey’s advisors wanted her to make a chair into a character and perform with it. Cliché alert! Take cover. She didn’t, and we should be grateful. Wipe your mind of all the anguished chair dances you’ve seen. In her opening solo, Lacey, profile to us, gets acquainted with one of the two folding chairs, trying things out with it— attempting risky balances on it, but always perfectly controlled. At first you might think that the text spoken by the unseen Cardona is a description of the chair: “This object has two stands connected to the ground and two parts hanging low.” But, no, he’s talking about Lacey—her planted feet, her dangling arms. When she undulates her spine in an uncannily thorough way, he mentions the object’s “ability to be snakelike.”

This studied dehumanization of a person is counterbalanced by Lacey’s second chair scene. Sitting on the floor beside her fold-up partner, she acknowledges that it is a chair, but also treats it as a friend who is about to become something more. Her monologue is both droll and strangely tender. Speaking as if the two were having coffee together, occasionally giggling nervously, she happens to mention Charles and Ray Eames—“you know, the Eames chair.” Then sensing a reaction from her companion, she says quickly, “I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings” (or words to that effect). The conversation turns to the Scandinavian chair she grew up with and touches on socialism in Sweden. Gradually, Lacey finds the chair more and more attractive. By the time Cardona returns to involve the other chair in his scenario, and Bepler’s light chords and ticking sounds give way to drums and stronger piano sounds, Lacey is slowly moving her chair upstage, rubbing her crotch dreamily on its seat.

Lacey has a final appearance. Wearing a version of a little girl’s white sailor dress, she moves in dim light like a gentle robot or a very nice doll come to life. To high piping joined by rougher horn sounds, she walks on tiptoe, turning this way and that, repeating a few precise gestures. It’s a beautifully understated performance.

In the end, Cardona opens the black curtain at the back to reveal a blindingly white canvas. He and Lacey don’t stay long. They exit quietly, hand in hand, leaving us to listen to the music and watch the luminous display that Dunn creates on the white backdrop. Concentric suns and constellations pulsing and transforming, mist and clouds, colors leaking into sunrises and sunsets.

Words heard just before this hint at underlying thoughts. I catch only a few—“a soft wind entering the body,” “a machine with a heart,” something about evolution, reaction, satisfaction, and finally, “it was beautiful.”

The residue of all the theories and ideas and desires that these two extraordinary artists asked to have projected onto them creates a texture rife with enigmas and queries about, I think, what it means to be human. Puzzling Tool Is Loot may be, but it’s exhilarating watching superb performers approach dancing as if it were an archaeological site yielding perplexing, yet intriguing shards.

it is such a joy to have your writing again back where we can read it. your open eye, and open mind is a postive after so much negative and uninformed dance writing especially in the NY Times.

being in the profession both as a performer and writer, you have the experience and knowledge to offer insight into the establishment and the new comers in this butterfly of an art form. your point of view if rarely negative or preconcieved. and if you find somethings that you do not agree with you generally try to ground it into facts and reality.

please continue.

joel schnee