It is 1979; it is 2011. It’s 1981; no it’s 2011. Bill T. Jones wears glasses now, and I can’t read without mine. Arnie Zane died in 1988; his spirit and his name live on in the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. In the 1960s, I was a founding member of Dance Theater Workshop. In the 1970s, Bill made his ferocious New York debut as a soloist on that organization’s Fresh Tracks series. In 2011, his company and DTW merged in New York Live Arts. Forgive me if my head is spinning.

NYLA’s 2011-2012 offerings at the 219 West 19th Street theater include the Replay Series—revivals of key works seen at DTW over the past decades. Fittingly, Jones’s group opened the season with “Body Against Body”—two programs (September 16 through 25) of early Jones-Zane duets, a trio, and a Zane solo, later re-envisioned for a group by Jones. I regretfully missed seeing the program featuring Duet X Two (1982, reconstructed 2003) and Blauvelt Mountain (A Fiction) (1980, reconstructed 2002). The latter, performed by Jennifer Nugent and Paul Mattheson—a brilliant couple very different from Jones and Zane—would surely have rocked my unconscious sense of watching a collection of palimpsests—with elements of the original performances shimmering beneath the present-day manifestations.

People who saw Jones and Zane’s collaborative Monkey Run Road in 1979 at the old Kitchen Center loft at Wooster and Broome were stunned. Who were these two young guys who’d come out of the blue, these partners who’d met upstate at SUNY-Binghamton. In those days, we were struck by their odd-couple charm—a tall, slim African American man (Jones), who could be as sinuous as a snake, and a shorter, stockier white man (Zane), who hit every movement with formidable precision. But also compelling was their craftsmanship. And that fact makes their early work seem still timely, and more powerful than many of today’s more elaborate postmodern works.

They were right in tune with the downtown zeitgeist of the 1970s, when Trisha Brown was designing plain, elegant, brainy structures for generating movement, Lucida Childs was building fastidiously patterned webs of dancing, and Laura Dean was turning repetition into what amounted to secular rituals. Watching Monkey Run Road—both then and now—is like watching a wind blow the vanes of a mobile into different intersections.

Talli Jackson is tall; Erick Montes is shorter. There the resemblance to the original performers ends, but Jones’s slightly sardonic gravity and Zane’s intermittent, tag-along playfulness still infuse the choreography. And these men are terrific, although Jackson—jaw set and mouth turned slightly down—can seem more aggressively sober than Jones was. The opening introduces you to the joys of repetition. The two performers push a very large wooden box to the center of the stage, confer in an undertone, move it back to its original place downstage left, and center it all over again, before sitting on it side by side. Throughout, everyday behavior butts heads with artistic formality. As Helen Thorington’s score begins the discreet scraping, banging, and ringing sounds that convey both the forthrightness and the sensuousness of the choreography, the men begin to lay out the dance.

The movements are big and clearly etched in space: lunges, somersaults, swiped or jabbed gestures, poses. As the men repeat and add to the material first shown in a brief solo by Montes, we get to know it very well. They perform everything as a task—walking again and again, say, to the same spot on the stage to begin a new sequence or repeat an old one. In its permutations and variations, Monkey Run Roadresembles a relationship. Try this. Would it be better if we did it another way? Would you rather manage it together or apart? So, for example, we see one man embracing a space into which his companion’s body formerly fitted, while the other assumes his own role in the joint maneuver at some distance. They dip into each other’s vocabulary of steps, intersect, alter the tempos.

Even the few words they speak vary slightly in detail with each repetition. Jackson stands on one leg, while Montes revolves him by using Jackson’s lifted leg as a lever; meanwhile, Jackson recites the list of names (Jones’s siblings, I believe) and facts that we heard earlier in Jones’s recorded voice. Zane on tape speaks German, Montes live speaks Spanish. Every time Montes shakes out his legs between sequence, it’s a bit different, but the fact that he does it at similar moments and in the same spot onstage gives the informal wriggle the status of a compositional element.

The men are always watchful, aware of each other. Twice, they’re sitting gravely, side by side, on the box. Montes gets down. Jackson eyes him and relaxes into a leaning-back, spread-legged posture. Without hesitation, Montes climbs onto his lap and nestles there. The warmth that emanates from all their energetic, matter-of-fact activities bespeaks the long-ago relationship embedded in the choreography. For what seems like a very long time, Jackson walks around the stage with Montes curled up in his arms. As collaborators and lovers, Arnie and Bill agreed, argued, walked out the door, finished each other’s sentences, and competed. All that is in the dance and in the current performance.

The most startling moment comes when Montes, bursts through a hitherto unnoticed door in the side of the box; in a second, he’s on Jackson’s shoulder, flying. There’s only one repeat of that, and it ends Monkey Run Road.

At each NYLA performance of Valley Cottage: A Study (1980/1981), the roles created by Jones and Zane were played by various pairs of company members: two men, two women, a man and a woman. The night I attended, Jackson and Montes performed this piece as well as Monkey Run Road. (Its title, like that of the earlier work, refers to a place where Jones and Zane lived together.)

In Valley Cottage, Robert Wierzel’s lighting creates a diagonal that bisects the stage, with its farther portion darker than its nearer one. At one point, the men become silhouettes. Children call out amid the low tones and guitar notes in Thorington’s score. The taped voices suggest that they’re chatting while strolling around the neighborhood; maybe they’ll take a swim. They remember incidents and debate about them. A letter is read.

Jones had the wit to install a phrase from Monkey Run Road in Valley Cottage. (Why not? You move, you bring a suitcase of stuff you need.) The nature of the men’s interactions hasn’t changed. Same relationship, a few years later. Montes is a bit more playful than he was in the earlier work, especially when he traipses repeatedly across the floor after Jackson. The two perform solos, sometimes simultaneously, and Jackson’s is complex in its interplay between decisive power and softness—a playing-around with ideas and moods. Here, too, the choreography captures the rhythm and behavior of daily life and uses it to cloak an immaculately worked-out scaffolding. I remember that in 1981, while parsing the piece’s permutations and thinking how clever it all was, I was also wishing I might walk down a road in Valley Cottage, New York, and run into Bill and Arnie.

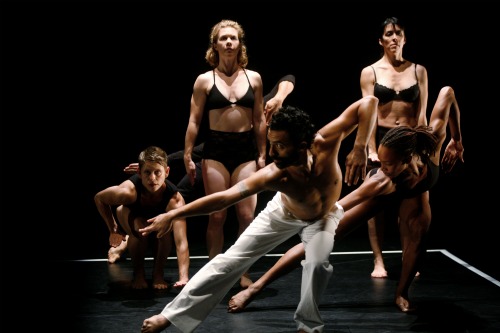

Continuous Replay, which separated the two duets on the NYLA program, began as a 1977 solo, made by Zane and performed by him with fierce exactitude and compressed force. Revised by Jones in 1992, it’s now a group dance—with Jones/Zane dancers augmented at each performance by between five and eight guests. You can have a lot of fun recognizing former company members, dancers from other groups (e.g. several Martha Graham performers, a couple of Merce Cunningham’s people) and independent choreographers.

Zane must have been channeling Trisha Brown when he made this work. It’s a chain of gestural movements and poses that accumulate, one at a time, while always returning to the initial step. Every action is struck with the sharp clarity of a stick hitting a block of wood. The procession is also an accumulation. New members enter and join as the trail crosses the back of the stage, turns a corner to come toward the spectators, turns again, and crosses the stage at the front.

In expanding Continuous Replay into a group work, Jones softened its remorselessness for 1990s eyes. The slow crawl of the accumulation in space and time is broken by various individuals racing across the back of the stage and into the wings. That gambit also makes costume changes possible. By way of development, Jones asks the performers to begin naked (the night I attended, almost all complied), to reappear (now one, now another) wearing black items of clothing, and finally to dress all in white (an apparently affectless idea of development that’s a throwback to the 1970s but no less interesting today).

While Montes, as “the clock,” keeps the phrase going, others begin to make individual variants, but intermittently—and seemingly at their own discretion—they drop back into synch with him. Toward the end, various company members (Antonio Brown, Shayla-Vie Jenkins, LaMichael Leonard, Jr., I-Ling Liu, Jenna Riegel, Jackson, Matteson, Nugent) dance briefly and wonderfully in the now empty half of the stage where the piece began. Liu gets a chance to be slowly, elegantly remarkable with her long legs, alone in a square of light.

It is 2011.

Lovely Deborah, brings back memories of seeing Continuous Replay out here, of seeing Arnie Zane dancing in a piece I don’t remember the title of, but he performed in a raincoat and the sound it seems to me was of the movement of a train, of the epiphanies Jones and Zane gave us of a wide range of dancing bodies in their early work. As always, I am grateful for the context that only you can give. Thank you.

Arnie Zane’s talking in Monkey Run Road was in Dutch, not German, a speech by Queen Juliana.I don’t know what the speech was about.

-mbs

I’m grateful to my friend and colleague, Marcia S., for pointing this out. That makes sense. Bill and Arnie lived in the Netherlands for a while.