Stand in a summer field at dusk, and you’re surrounded by a silence that only seems silent. Intermittently a bird calls, a wild apple falls from a tree, a sudden wind ruffles leaves. In the distance, a figure bends down to pick something. On a busy city street, it’s almost impossible not to be in motion and enveloped by motion and noise. The soundscape is dense with the whoosh of traffic, human babble, horns, sirens.

These thoughts were stirred up by the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s performances at Bard College, September 9 through 11. The program opened with Cunningham’s Suite for Five (1956-58), an essay in stillness, punctuated by clear, serene bursts of motion and intermittent musical tones. The final work was the 1975 Sounddance, a carnival of high intensity, high density visual and aural patterns. In between these, a kind of unintended buffer: Antic Meet (1958), a witty revue made up of eccentric little acts—a performance about a performance.

Cunningham composed Suite for Five by the same chance methods that John Cage employed in writing its score (from his Music for Piano). The process involved marking the imperfections in sheets of transparent paper to determine spatial patterns (in the 1950s, we were all conversant with high-quality bond, onionskin, and tracing paper) and layering them over one another to find where dancers would intersect. Placing these over sheet music paper might yield a time element.

Perhaps as a result of this process, Suite for Five is as much about silence and stillness as it is about sound and motion. Each single tone that pianist Joseph Kubera chooses to draw from his instrument—whether by pressing a key, plucking a string, or tapping the wood— falls into the silence like a small stone into a pond and seems unique in beauty and resonance. When Daniel Madoff begins the piece in a near corner of the stage, his every move has a similar clarity. Squatting, he slowly slides one foot forward and stretches his leg, then returns it and stretches the other; the image—somewhat like an elegant, slow-motion line drawing of that lusty Russian step, the prisyadka—burns itself onto the luminous stage and into your brain.

In the 1950s, Cunningham’s company was small, and the dancers in Suite for Five only occasionally appear at the same time. In the final quintet and in the trio performed at Bard by Rashaun Mitchell, Marcie Munnerlyn, and Jamie Scott, people most often pursue separate activities at different speeds. One of them may skitter around with fast little steps, another unfurl a slow balance, another stride into deep, wide lunges. If they meet, it seems as if by accident and without warning, which results in such images as Munnerlyn and Scott standing close together, facing each other, while Mitchell supports himself in a precarious slant low to the floor by putting his arms around both women’s waists and holding tight.

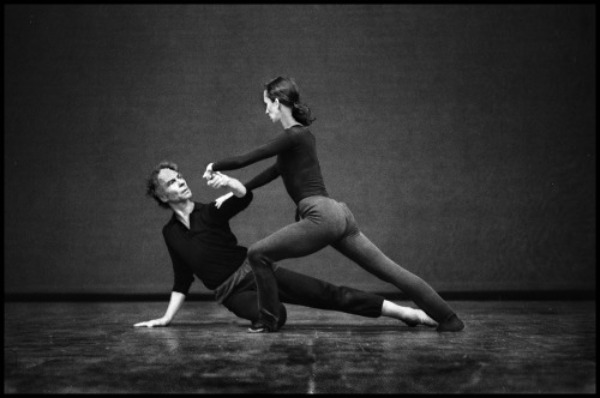

The duet, originally performed by Cunningham and Carolyn Brown (and danced at Bard by Madoff and Andrea Weber), evokes a ballet pas de deux in some subtle, fascinatingly disarranged way. In Beverly Emmons’s shading-into-night illumination, Madoff kneels, bearing Weber, stretched out in flight on his shoulder; slowly and carefully he revolves without disturbing her equipoise. Or she leans, slanting against him; or he crouches, cradling her. Without warning together they explode into a spate of jumps like ballet sissonnes.

I’ve heard people describe Cunningham movements as “balletic.” It’s true that he favors articulate, turned-out legs that swoop high; finely arched feet; and an elongated spine. Yet these movements are performed without ballet’s look-at-the-picture manner or the time-honored emphasis on beauty of line. And deviations abound. In Sounddance, Apollonian calm is sorely tested. How swiftly can a dancer stalk around on tiptoe? How rapidly thrash into a position and out of it again? How intersect with others in formations that could easily become train wrecks?

I’ve heard people describe Cunningham movements as “balletic.” It’s true that he favors articulate, turned-out legs that swoop high; finely arched feet; and an elongated spine. Yet these movements are performed without ballet’s look-at-the-picture manner or the time-honored emphasis on beauty of line. And deviations abound. In Sounddance, Apollonian calm is sorely tested. How swiftly can a dancer stalk around on tiptoe? How rapidly thrash into a position and out of it again? How intersect with others in formations that could easily become train wrecks?

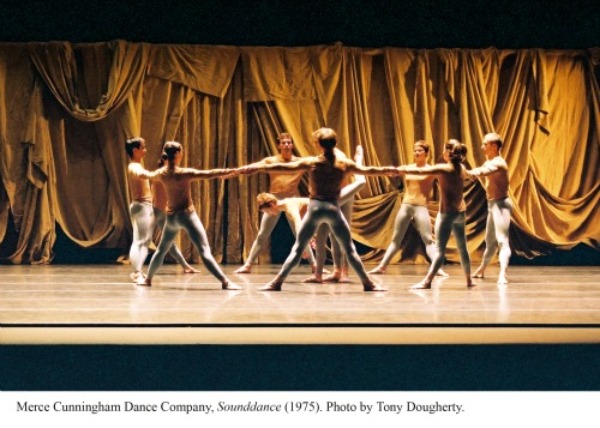

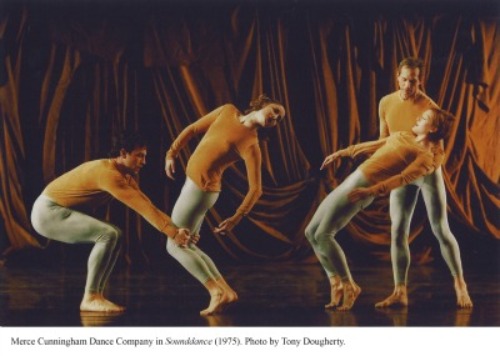

Mark Lancaster’s set is an elaborately draped curtain that spans the stage, but hangs from a bar only the height of a ceiling, with a black space above it. Through a hidden gap at its center burst the dancers, costumed identically in pale blue tights and snug gold tops. Rushing in one at a time, they might be circus performers late for an entrance, but they set about performing without fanfare. They are surrounded by David Tudor’s thunderous score (electronically manipulated by John King). Listening to it is like being inside a storm, with all the variations in timbre and tone sliding around but never stopping. The dancers ride it like people hastening to finish all they have to do before a tornado strikes—jumping, leaping, prancing, ducking under or vaulting over barriers, flocking, hanging onto one another to accomplish an intricate task.

Various of the ten superb and valiant company members (Robert Swinston, Brandon Collwes, Jennifer Goggans, Silas Riener, Melissa Toogood, John Hinrichs, Mitchell, Munnerlyn, Scott, and Weber) may join briefly in unison dancing, but more often they’re racing about—with Swinston, in Cunningham’s role, often seeming to supervise or complete a pattern, or to prevent someone from being blown away. The stage is awash with activity that keeps precision and wildness in balance. At one point, three men repeatedly swing a woman high, the bridge her body forms angled now this way, now that. Meanwhile, in the background, Swinston and three others, linked together, twist and pull against their clasped hands.

I learned from David Vaughan’s magnificent and magisterial book, Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years, that just before Cunningham composed Sounddance, he had been given a microscope and was enthralled by the wiggling organisms it revealed. That may explain why I scribbled “DANTE” in my Bard program. In several clusters, waving their arms about, the dancers suggest snake pits or souls writhing in an inferno of their own making.

When, in the end, the performers exit singly or close behind one another, they look as if they’re tearing themselves away, or being sucked offstage by a powerful force. Swinston, as ringmaster of this diabolic circus, is the last to leave, and he doesn’t waste a second bolting through the golden curtain.

Antic Meets acts as a leavening to these two pieces. If you dreamed of vaudeville gone awry, you couldn’t come up with anything this seriously zany. Christopher McIntyre’s occasionally braying trombone contributes mightily to the ruckus stirred up in John Cage’s music by Kubera’s piano, David Behrman’s violin, and John King’s viola.

A woman (Goggans) who emerges from a free-standing door that seemingly walks by itself dances sweetly with a man (Madoff) who has a chair strapped to his back (handy when she needs to rest and preen). Goggans and Krista Nelson do pretty-footed stuff like semi-ballerinas but also mime their rivalry; Nelson lobs invisible stones, Goggans retaliates by sloshing an invisible bucket of water at her. In the section “Bacchus and Cohorts,” Daniel Madoff struggles to find openings in the many-armed sweater he’s trapped in, while Goggans, Nelson, Toogood, and Emma Desjardins stalk about in the wonderful parachute dresses devised by Robert Rauschenberg, looking suspiciously like a Martha Graham chorus—only more insouciantly threatening. Madoff—valiantly slapping his swaying hips, even though he has given up on finding a hole to poke his head through—finally gestures “begone!” and they oblige.

Even though these performers (Dylan Crossman is the sixth member of the cast) sometimes muff the comic timing and dramatic flair that Cunningham excelled at (thereby obscuring some of the points he was making), they attack the ten “numbers” in this artful and endearing little satire with verve.

Knowing that MCDC will disappear after December 31, 2011, fans and first-timers flock to every performance they can. We may never again see dancers who’ve been schooled by the choreographer perform these works. There’s no stigma attached to hoarding when we’re collecting memories to get us through the Cunningham-sparse winter to come.

Since I find it nearly impossible to write about Cunningham’s work myself, (I think he says it all, without words, and I have nothing whatever to add except my admiration) I am grateful indeed for Deborah’s eloquent review of a program I will see in Seattle next month. How can we feel anything but elegiac, knowing it’s our last chance to see these dancers, balletic or not, and we’re all in Deborah’s debt for clarifying that particular point. I’m looking forward to seeing Biped in Seattle, too, an example of Merce’s embrace of the latest tools at hand. By chance or not, he was always the man in charge.

I’m afraid that Deborah has given us one extra month in which to savor Cunningham, as I believe that the company will be closed down on January 1, 2012, rather than January 31st. Wishful thinking indeed!

I’m grateful to George Dorris for catching my error. The company’s final performance takes place on December 31, 2011. The correction has been made.