Here’s a fairy tale for 2011. Once upon a time, a very important knight—one of the great musicians of the late 20thcentury—joined forces with an adept ruler-choreographer (also a knight) who had inherited a powerful kingdom of dance. They set out together on a quest to find the true grail—a beautiful ballet that would further ennoble them both and maybe even bring in money. As far as we know, they underwent no terrible ordeals, battled no giants, slew no dragons. Eventually they fell together into a nicely decorated pit and rode home bearing The Ballet. It is possible that someone or something had placed them under a spell.

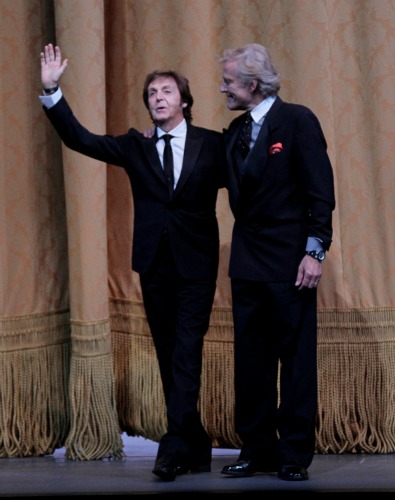

The work that the New York City Ballet premiered at its September 22 Gala is called Ocean’s Kingdom, but the title in ads, and on the program cover that evening, was “Paul McCartney’s Ocean’s Kingdom,” and Sir Paul was present in the theater to receive the audience’s cheers and the wave of affection and respect emanating from the company and its music director, Fayçal Karoui. Karoui, an engaging speaker, opened the evening by leading the orchestra in adroitly chosen passages from the score to demonstrate how aptly McCartney’s music conveyed mood and character, and used rhythms and percussion to create a sense of urgency.

Indeed the music is very attractive. Beginning in the 1990s, the former Beatle and master songwriter became interested in classical composition, and the score he wrote for Ocean’s Kingdom (arranged by John Wilson and the composer and orchestrated by Andrew Cottee) has the lushly atmospheric, melodic quality of late 19th-century ballet music, although development is not one of its strong points.

A lack of development in terms of character and drama is also the ballet’s major flaw. McCartney wrote the scenario, but he isn’t entirely to blame for this. Peter Martins, bred in Denmark’s Bournonville tradition, should know how to tell a story; his mentor, George Balanchine, certainly did, although he rarely wanted to. To carry my fairytale metaphor further: Something happened to that supposed grail on the journey home through the forest. The knights needed a dramaturge to ride with them.

The tale is a simple one. There are two kingdoms: Ocean and Terra. They don’t seem particularly rivalrous, and their inhabitants are apparently able to breathe in both atmospheres. King Terra comes in person, with his younger brother, Prince Stone, and a retinue of “Terra Punks” to invite King Ocean and his beautiful, virtuous daughter, Honorata, to a Terra ball. (Get ready to fade the blue lights and rippling projections and bring up the reds.)

A Romeo and Juliet moment ensues. Prince Stone and Princess Honorata are soulmates. But it turns out that Honorata’s principal lady-in-waiting, Scala, is profoundly, unaccountably evil. So, once the water people are in the earthly palace, she connives with King Terra, who (the program says) wants Honorata for himself. Soon she is in a prison of light. But Scala’s hard heart softens at the sight of true love. Luckily, she has magic powers. She not only melts the prison bars and guides the lovers to an escape route; she rushes back toward their pursuers and conjures up a whale of a fire-and-smoke deterent. Many Terrans are killed, but, alas, she is collateral damage.

King Terra (Amar Ramasar) and Scala (Georgina Pazcoguin) threaten the lovers (Sara Mearns and Robert Fairchild). Photo: Paul Kolnik

Back under the sea, King Ocean (Christian Tworzyanski doing his best in an sketchily designed role) and his court are very glad to welcome the princess and her beloved (did all the sea folk just go quietly home without wondering where Honorata could have got to?). Scala’s spirit even appears at the final curtain to bless the pair, but there’s not much of a celebration. Those still alive will live happily ever after.

It’s as if Martins wanted to tell a story without really telling a story. The key villains, King Terra and Scala, are two-dimensional and their motivations aren’t clear. How could someone as evil as Scala keep an important job in the drifty kingdom? If she were simply a bit flawed, King Terra could bribe her, and we might have a sneaky little pas deux by those vivid and expressive performers Amar Ramasar and Georgina Pazcoguin, instead of just seeing them skulk in the shadows at the back. And, speaking of duets, it’s strange that Martins chose not to depict choreographically (or really in any other potent way) this stated lust of King Terra’s for Honorata. Or even to make it evident that Terra and Stone are rivals. How hard would it have been to do that? Would the ballet have been deemed too long? Did Sir Paul not write enough music?

The ballet’s other surprise is that Martins isn’t working at the top of his form. The most compelling sequences in terms of movement belong to the Terra Punks—a squad of men who excel at twisty leaps. They also have the best of the costumes that fashion designer Stella McCartney came up with: nude body suits decorated with killer tattoos that look like fancy crocheting. The ocean people’s dancing is pretty and bland—lots of bourrées, walks, and runs, and all but a few dancers are burdened with blousy blue tunics and, for women, skirts that are short in front and long in back.

Martins has made a number of splendid pas de deux in the past, but those for Ocean’s Kingdom’s two wonderful leading dancers, Sara Mearns and Robert Fairchild, often look as if they’ve been cut from a bolt of duets-by-the-yard in some ballet warehouse. One lovely moment: Fairchild takes Mearns’s hand and, using her straight arm as a lever, propels her into a turn; then she returns the favor. Spinning alternately, they advance toward us, as fascinated by each other as children with a new toy. Possibly Martins didn’t want dances to stop the forward motion of the drama by calling attention to themselves. But we don’t really get to know or care much about his fairly helpless hero and heroine and the nuances of their emotions. Mearns seems to be in a perpetual backbend, undone by love.

There are some entertainers at the party: an “Exotic Couple” (Megan LeCrone and Craig Hall) who don’t behave very exotically, two “Amazon Women” (Savannah Lowery and Emily Kikta), almost invisible under a storm of vividly colored fabric and headdresses, and the leader of the revels (Daniel Ulbricht—in a handsomely gaudy, formfitting costume and a yellow wig—doing some of the marvelous jumping he’s known for).

In addition to the costumes by S. McCartney, the look of the ballet is credited to S. Katy Davis for the video and slide projections, Perry Silvey for the minimal set, and Mark Stanley for the ingenious lighting. The audience at the Gala accorded the ballet a standing ovation. It will be given more performances this season and in the seasons to come. Ocean’s Kingdom seems to me to be less the hoped-for grail than a damsel in some distress, in need of a bit of rescuing.

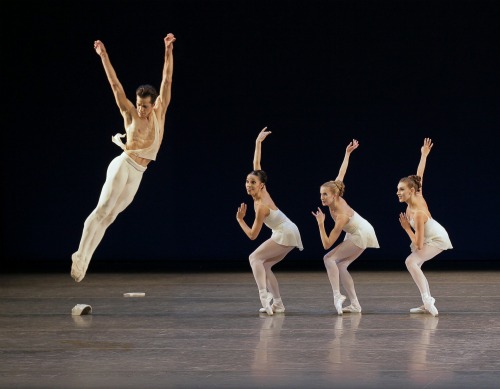

Apollo (Robert Fairchild) dazzling the Muses (l. to r.: Ana Sophia Scheller, Sterling Hyltin, Tyler Peck). Photo: Paul Kolnik

It’s unusual to see Robert Fairchild as a cipher. He brings so much to every role. His Apollo was the highlight of NYCB’s brilliant “Balanchine Black & White” program on Tuesday, September 20th. An evening spent drinking in Episodes, Apollo, and The Four Temperaments doesn’t send me reeling into the streets; it reminds me that dancing molded by a master’s hand is one of the things I love best in the world.

Fairchild’s Apollo isn’t the bold, yet imperturbable blond god that Peter Martins once played; nor is he the quicksilver youth portrayed by Chase Finlay, who made his debut in the role last spring. On the other hand, he’s not as much an everyman as Jacques d’Amboise some years ago or the boisterous boy that Baryshnikov brought to life. Fairchild makes you see Apollo’s struggle between classical serenity and impetuousness, which gradually resolves over the course of the ballet in both Balanchine’s 1928 choreography and Igor Stravinsky’s music. There’s time to play with these frisky muses and see if the godling can harness them together, but decisions must be made and authority exerted.

In addition to his technical accomplishments, Fairchild seems to have a natural aptitude for acting. He regards the lute in his hands with interest and slight bafflement, as if not sure of his talent but willing to believe in it. His gaze and quality of attentiveness almost always anticipate what he will do next. His grasp of dynamics molds and enlivens his dancing. On Tuesday, he had some gifted muses vying to be the most favored: Sterling Hyltin as the winner, Terpsichore; Tyler Peck as Polyhymnia; and Ana Sophia Scheller as Calliope. At one robustly jazzy moment, Peck and Scheller were so perfectly matched that they looked like best friends who’d practiced together every day after school.

There were other standouts that night, along with others still working their way into the choreography. Teresa Reichlen and Ask la Cour gave a fine reading of the haunted duet in Episodes, with Anton von Webern’s music whining delicately around them. Wendy Whelan and Craig Hall work beautifully together in the ballet’s third movement, and Ashley Bouder is sensationally vibrant in the “Choleric” variation in Paul Hindemith’s Four Temperaments. No wonder she scares the men away; watch out for those flashing legs! Now there’s a story for you!

I know, I know, I should look up what a burre is. Well, as the start of a season begins, this did not want me to buy

a ticket to the ballet. My brother, however, has become interested in ballet, The Washington Ballet, to be precise and so I’m trying to stray. I didn’t “see the dance” as much as hear the story, which seems lame. Michelle, my belle, Mother Nature’s Son, how could you do this to us? I don’t expect much of Peter Martins, but he had an impossible act, according to most criticism I’ve read, to follow.

I was comparing your plot synopsis here with the one you’ve got of Little Humpbacked Horse — they both seem pretty far-fetched. Though I suppose Bournonville worked with some even sillier.

Do we really expect story ballets to have realistic plots? So many feathered maidens, hapless heroes (and certainly the one in Ocean’s Kingdom sounds, not only by Deborah’s account but several others, hopelessly hapless). But maybe Sandi has hit on something here–story ballets created in the 21st century, despite such visual updatings as tribal scarring or tattoos for the villains, perhaps need to reflect our reality in some way in the narrative.

The review of Apollo made me think about this in different terms however; what is it that makes that ballet “universal” in its message that Ocean’s Kingdom lacks? And I’m speaking about the narrative here, not the choreography needless to say.

I haven’t seen Ocean’s Kingdom, but it sounds as though a major problem is that the ballet doesn’t take the plot seriously enough (however absurd). Balanchine understood that a story ballet needs clarity, pacing, & excitement, as in his Midsummer Night’s Dream & Coppelia, and even his one-act versions of Swan Lake & Firebird keep their action streamlined and straightforward. But he also created ballets with just a wisp of plot, & in those (Serenade, Apollo [esp in its truncated 1979 form], La Valse, many others), the story grows symbolic and ethereal, gesturing deeply towards allegory, which seemed Balanchine’s natural element. Ratmansky’s Bright Stream also keeps the action clear and shapes an old-fashioned tale that yields a modern vision of community and harmony. I don’t think 21C narrative ballet needs realism in the least–it’s impossible. Look at Ratmansky’s Namouna, which satirizes 19C ballet with a slew of delicious absurdities but also provides a tongue in cheek plot: it’s not in the least realistic, it feels at times like an MGM nightmare, and it doesn’t take itself very seriously as a story. But it does take itself seriously as dance, it offers all the narrative and choreographic satisfactions of a rousing romantic tale, and it achieves a consummation. It’s a terrific ballet. Martins has made at least one strong narrative ballet (Sleeping Beauty) & one absorbing but flawed one (Romeo + Juliet), but it may be that the apparently underdeveloped materials of Ocean’s Kingdom didn’t inspire a commitment to the dramatic needs of narrative dance. It’s hard work to get a narrative across choreographically.

Does Ringo’s “Octopus’s Garden” get alluded to in the score?

Just as Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake reflect a 19th century reality (the continuation of royal line), without God knows a trace of what we think of as realism, I simply meant that 21st century narrative ballets could possibly be more viable if they appealed to the concerns of 21st century people. Fantasy is always rooted in some form of reality.

Having said that, I completely agree that it’s hard work to get a narrative across choreographically, even if it’s based on an already existing story.