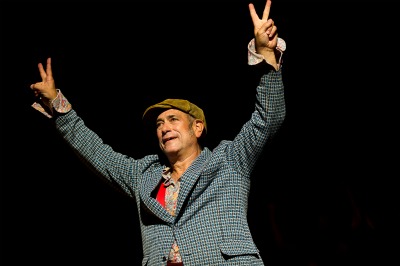

David Dorfman’s Prophets of Funk might well be subtitled The Way We Were. He first heard Sly and the Family Stone as a college freshman, back in 1973, and no doubt mourned the band’s demise in 1983. When the Jacob’s Pillow audience gets its first look at Dorfman during the work’s August run there, he’s surely channeling his younger self. Advancing along a diagonal—a bulky man, limber in his loose clothes, strutting and wiggling and kicking high to the boom-boom of music by Sylvester Stewart (aka Sly Stone)—he’s in heaven. The disconnect between the memory and the reality is endearing. How Dorfman loved those songs! How he still loves them. Cue the canned applause and the flashing red lights.

Trailing him is tall, skinny, be-wigged Raja Kelly—Sly to the life, his Afro wig the size of a beach ball. Shades, platform shoes, sequined jacket—at one time or another in the piece, Kelly’s got them all.

Dorfman wants us to love this music too. While the spectators are entering the theater, some of them accept the invitation to come onstage and learn the steps of a line dance. They’re digging it, and when that phrase appears later in the Prophets of Funk—whether we watched the lesson or participated—we recognize it, and our muscles very subliminally twitch.

Confession: I wasn’t a huge Stone fan in the 1960s. James Brown was more my guy. And the Beatles always got me dancing. But, like Dorfman, I admired the fact that Sly and the Family Stone was integrated both racially and in terms of gender—a rarity back then. The band grooved on the political urgencies of the day. The sexy, insistent “If You Want Me to Stay” (1973) was preceded in 1969 by “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey.”

Dorfman has always choreographed big-hearted, idea-driven, smart, shaggy pieces. Since 2006 and his underground, he has been querying violence. When is it justified? Is it ever justified? That piece, focusing on the Weather Underground, was followed in 2009 by Disavowal, a powerful inquiry into the issues surrounding fiery abolitionist John Brown (and much more). Hero? Rabble rouser? Brown led his followers into death. In part because of the music, Prophets of Funk treats the racism, student activism, and city-streets violence of the 1960s with a softer touch. As dancer Whitney Tucker says, in a speech about a 15-year-old’s political confusion back when a protest could degenerate into looting, “ All we had was this.” Meaning hearing this music and dancing yourself blind to it.

The gifted cast of Prophets of Funk (eight in addition to Dorfman) is appropriately variegated in terms of age, size, race, and gender. The lighting (by David Weiner in association with Dans Sheehan); the sensuous, vividly colored video projections (media design by Jacob Pinholster); and the hip costumes by Amanda Bujak telegraph the hot theatricality of the disco era and the sartorial daring of self-proclaimed free spirits like those who flocked to Woodstock in 1969 (Tucker sports a blonde afro). Dorfman gives a postmodern edge to the musico-cultural ambiance.

There’s a built-in problem involved in evoking a decade and honoring its pop tunes yet not gussying them up with too-polished steps. For a while, I’m charmed by the line dancing and the carryings-on (Luke Gutgsell in the background, playing the hell out of an air guitar; Gutgsell, Kyle Abraham, Meghan Bowden, and Karl Rogers acting wasted; the gender-blind duets; a burst of terrific dancing by Renuka Hines). But after a while, the partying begins to look like something I’d rather be doing than watching. I start wishing Dorfman would let the choreography get a little more off-beat in terms of rhythm and design. A little less. . .well, real. (On the other hand, later in the piece, when Kendra Portier, highlighted in a solo, tosses one leg up in a sort-of arabesque, it’s a shock).

I absorb the dilemma, but, almost immediately, everything gets interesting again. Hines has fallen, and Gutgsell crouches by her side, cradling her. Then Portier walks in, looks at them and quietly replaces Hines. Then Kelly replaces Gutsgell. And so on. The distanced view of violence’s aftermath knocks home both the communal spirit and the not-always-anticipated aggression that protesters faced.

You wanted to be a joiner, but who and what to join? Were you at Kent State on May 4, 1970? Were you blissed out in the Woodstock mud? What bandwagon to jump on? Dorfman tackles the issues in an unexpected way. The group is trying out moves, and Abraham—eager, happy, fast-talking—wants to appropriate them all. “That’s my step!” he exults, over and over, grinning enough to split his face. He mimics their lively, vigorous actions but has to keep stopping so he can notify us of his claim. Abraham’s depiction of a sweet, young guy— fueled by the need to belong and possibly by uppers—is a major highlight of the piece.

Perhaps the performers’ frequent comings and goings in Prophets of Funk stand for something more important than leaving the party in order to piss or smoke.

But for all the references—cultural and personal and political—the music, the dancing, and the show-biz atmosphere never stop fizzing. The phrase that the audience learned is embedded in a sequence that’s rich and very good to look at. We hear a snatch of an awkward Dick Cavett interview with Sly, marvel at how convincingly Kelly lip-synchs a song, laugh when the performers strip down to reveal satin and fringe under their bulkier outfits. Dorfman makes two more forays along that path of light—the last time moving away from us, with Kelly as Sly following him down the road into darkness.

Coincidentally, the day before David Dorfman Dance’s first performance at Jacob’s Pillow, Sly Stone released I’m Back! Family and Friends, a new CD featuring re-recorded hits and three new songs. Can we ever go home again?

So good to have Deborah Jowitt writing again. This piece is a little masterpiece.

I am also not a huge Family Stone fan, but this insightful review makes me interested to see the piece regardless of my taste in music!