Of late, I’ve been having a recurring daydream—probably prompted by the Mariinsky Ballet’s recent season at the Metropolitan Opera House (July 11 through 16), as part of the Lincoln Center Festival. Ballet companies square off like kids on the playground. “Nyah, nyah! I’ve got more Ratmanskys than you do!” “You do not!” “Do so!” “Well I’ve got the best Ratmanskys.” “Take that back or I won’t share my candy bar with you.”

Ballets by Alexei Ratmansky have become hot commodities. Not only does he deliver beautifully crafted, imaginative, warm-hearted works; his range is surprising. If a ballet company orders up a piece by Jorma Elo, it can count on spectacularly odd dislocations and knotty tangles of dancerly limbs. Ratmansky may deliver a surprise. Who’d have imagined that last year he’d give the New York City Ballet—a company that rarely goes in for storytelling—a stupendous remake of the 1882 Paris Opera Ballet extravaganza, Namouna? Or that, in 2009, he’d take the score and scenario that Prokofiev developed for Serge Lifar’s obscure 1932 Sur le Borysthène and give American Ballet Theatre On the Dnieper?

Ratmansky signed on as ABT’s resident choreographer in 2008 and recently extended his contract until 2023. He premiered a delicious Nutcracker for the company in 2010, and, for the 2011 spring season, created a lovely pure-dance work, Dumbarton— set to Stravinsky’s Concerto in E-flat, (Dumbarton Oaks), and mounted a production of The Bright Stream (created for the Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet, which Ratmansky directed from 2004 to 2008). This light-hearted tale of an important occasion on a soviet-era collective farm offers smart comedy and surprising performing opportunities (David Hallberg disguising himself as a sylph? Unforgettable). Nevertheless, NYCB, already possessed of the ravishing Russian Seasons (2006) and Concerto DSCH (2008), got Namouna in 2010. And Ratmansky still jobs around.

Few choreographers are as skillful as he at devising steps that weave about the music the way vines accommodate to a tree—understanding its contour while seeking adventurous new directions. Watching and listening to his choices, you cannot imagine the music-dance relationships any other way. He also shows us dancers as members of a particular society (in this he resembles Jerome Robbins). Even in the most formal and plotless of his ballets, people watch one another and respond to what’s happening. One might imagine that, during his seven years as a dancer with the Royal Danish Ballet, Ratmansky learned something from August Bournonville’s great 19th-century ballets about the importance of what’s happening in the background, as well as in the foreground.

If it were not for that attention to detail, I wouldn’t have recognized the Mariinsky Ballet’s Anna Karenina —one of two Ratmansky works the company brought to the Lincoln Center Festival—as being his. In fact, the conversational groups gathering far upstage in dim light or the excited crowd at a racetrack struck me as much more interesting than the anguished ecstasies of Anna and Count Vronsky.

Both of these ballets are set to scores composed by Rodion Shchedrin. Shchedrin interests Valery Gergiev, now artistic director and general director of the Mariinsky Theatre, and Gergiev conducts the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra with a power that brings out the music’s lyrical moments as well as its furiously emotional bombast.

Shchedrin wrote the music of Anna Karenina for his wife, ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, who choreographed the 1972 version and starred in it. To my mind, a ballet based on Leo Tolstoy’s great novel is a mistake to begin with. The book’s characters ponder their feelings, doubts, and hesitations more often than they express them. The ballet’s scenario leaves out two major plot elements that touch upon Tolstoy’s theme of infidelity. We don’t learn of Anna’s brother’s extramarital dalliances (lust simmers in this family) or of the on-again-off-again love between his wife’s sister, Kitty, and Konstantin Levin. All these people are onstage at various times, along with Anna’s friend Princess Shcherbatskaya (“Betsy”), Vronsky’s mother, and Kitty and Dolly’s parents, but their stories and, for the most part, their identities have been peeled away. Anna’s almost near-death experience bearing Vronsky’s child is reduced to her simply being very, very sick for unknown reasons.

Given the music and the nature of ballet, you could hardly expect a choreographer—even one as adroit as Ratmansky—to restore Tolstoy’s subtleties. Still, you watch the scenes at gatherings, balls, and racetracks thinking, “Is that Anna? No, it’s probably Kitty; so the man she’s doing a delighted pas de deux with must be Levin.” “So which is Betsy and which is Dolly?” “And is Anna’s husband, Alexei Karenin, the only gray-haired man, or. . . .?” So these characters buzz around in the background, meet and greet, dance, and watch events, and we focus primarily on Anna, Vronsky, Karenin, and her little son Seryosha. And trains.

Wendall Harrington’s video projections augment Mikael Melbye’s settings to great effect, whisking us from the Oblonsky’s palace to the Shcherbatsky’s salon to Karenin’s book-filled study. Projections of horse’s thundering hooves clue us in to the fact that all those handsome, leaping cadets (a clever number) are stand-ins for jockeys. Shots of a train speeding along a track lead up to the mock onstage train that bears down on Anna and in front of which she, ever so gracefully, throws herself.

There are effective moments and devices, like the revolving train car that carries a group of passengers including Anna and (at the last minute) the smitten Vronsky from Moscow to St. Petersburg. When it stops at a deserted snowy platform and Anna and Vronsky—emerging from opposite ends to get a breath of air—suddenly see each other, you feel a sense of forbidden passion far more than you do during the ensuing pas de deux.

Oddly, much of the dancing for the principals seems inorganic, full of ballet clichés. Whipping off a pirouette and unfolding one leg into an arabesque or a despairing developpé can’t be trusted to express a character’s entire rich gamut of emotions. And those reservations that war with passion are designed and projected in the SimpleText of push-pull-evade. Sometimes, too, the disconnect between plot elements and dancing is jarring. Although we expect dance steps to stand for feelings, when Anna enters her husband’s study and, after a bit of realistic mime, they do a little side-by-side dancing, I find myself thinking, “Why do that now? Sit down and talk.”

There’s no faulting the expertise of the performers. It took me most of the ballet, however, to warm to Ulyana Lopatkina, the Anna I saw. She’s a strong, bold, expressive dancer, but conveys little of the fragile reasoning and erotic longings associated with the character. Wearing a plain dark gray dress that made her look like an outsider from the start, she gave the impression that she could eat Vronsky for a late night supper. Later, as Anna’s situation grew more dire, Lopatkina became more believably vulnerable. Yuri Smekalov played Vronsky as both arrogant and—in his several solos— driven to maddened assaults on the air. Islom Baimuradov made Karenin into a convincing character, and Svetlana Ivanova was a charmingly effervescent Kitty in her one moment to shine —a sweet duet with Levin (Alexei Timofeyev), before she sent him packing, thinking Vronsky might propose.

I wished that I’d seen Anna Karenina at the Wednesday matinée and Ratmansky’s The Little Humpbacked Horse that evening, instead of the other way around. That way, I’d have gone out dancing into the hot city night.

The story of that magical horse began as fairy tale in verse by Pyotr Yershov (1815 – 1869). The author was still alive when choreographer Arthur Saint-Léon arrived in St. Petersburg from Paris in 1859 and, five years later, made Yershov’s story the subject of his first ballet on a Russian theme. Since the tale was banned for two decades because of its satirical characterization of a tsar, Saint-Léon made the ruler a Middle Eastern khan. Four choreographers re-worked Saint-Léon’s ballet before Ratmansky took it on. Shchedrin’s score replaced Cesare Pugni’s in 1960.

The basic plot has variants in other fairy tales. Three brothers—two well-set-up, arrogant, lazy fellows—are preferred by their father to the puny, gentle, not-so-smart youngest son. Guess who turns out to be the bravest and the smartest and wins the princess and the loot. This Ivan’s adventures include meeting a whole flock of firebirds and getting a very large magic feather (Yershov’s story incorporated elements of the tale on which Fokine’s ballet The Firebird was based) and visiting an under-the-sea ballet of the sort popular in 19th-century Paris and Copenhagen. Also he encounters three dancing horses, including two handsome ones that his brothers steal; he gets them back and gives them to the Tsar in exchange for a top position at the palace. The little humpbacked horse aids Ivan with his future assignments like finding the Tsar Maiden (who lives with the firebirds—don’t ask) whom the Tsar craves and diving for the ring that she demands (and which the Princess of the Sea helps him find).

Maxim Isayev’s costumes and set for this entrancing ballet hint that he may have been influenced by the geometric shapes favored by the Russian Suprematist artists. Positions, groupings, and other elements of the Ratmansky’s staging suggest carved folk figures or the illustrations in a children’s book, and Isayev’s palette makes the dancers look as bright as dolls. The naiveté of the story animates the performances too. Ivan isn’t the only innocent. The Tsar and the Tsar Maiden are wide-eyed and childlike, Ivan’s brothers are schoolyard bullies, and the Gentleman of the Bedchamber is an ineptly slimy villain. Shchedrin’s lusty music matches the many colorful sequences with cinematic shifts of texture and tone.

Ratmansky sets up the family in broad strokes. The brothers (Suslan Kulaev and Maxim Zyuzin) flank their bearded, bent-over father (the Mariinsky’s great character dancer, Vladmir Ponomarev). They barely move from their spot in front of a tiny red house, and many of their gestures and big, clunky, spraddle-legged steps are aimed at shoving Ivan (Vladimir Shklyarov in the cast I saw) out of the family triad or not letting him get a step in edgewise.

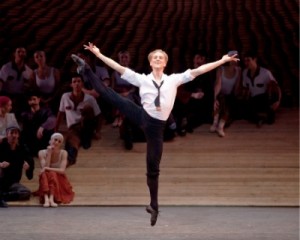

To add to the bedtime-story atmosphere, Ivan occasionally points out things to the audience with a gesture and an endearing grin (“See that funny little horse? What do you think?”). During the final pas de deux, after he’s not only won the Tsar Maiden but replaced the Tsar, Shklyarov tempers his quite amazing displays of elevation by muffing the ending of a diagonal of leaps and twice gesturing to the orchestra—and us—that he needs to try it again. (Shklyarov portrays Ivan with a marvelously believable mix of shyness and eagerness). After he has wowed the court and the audience with his jumping, he doesn’t leave the stage, but gestures to his beloved, “Now you dance, dearest,” which she does—ever so quick-footed. As the Tsar Maiden, Yevgenia Obraztsova is a charming fellow naïf—fiddling with her long pigtail (when she’s not coming onto Ivan with a bold kiss), bounding nimbly about, and queening it over the friendly firebirds like a decoration on a wedding cake. Obraztsova is wonderfully pliant in her dancing, suspending her balances as if she were half bird herself.

Vasily Tkachenko is frisky and agile in the title role. (I like the way he sits and massages his calves after the last long journey and magical denouement he has masterminded.) Andrei Ivanov’s bearded Tsar comes across as comically infantile, especially compared to the huge, block-like throne on which he is wheeled around by the Gentleman of the Bedchamber (Baimuradov) and later by that court official’s successor, Ivan. Six identically clad young “Wet-Nurses” hover over the ruler—one spooning soup into his mouth and all of them tickling him before putting him to bed (on a small block-like structure that doubles as a bench). He loves the Tsar Maiden brought to him by Ivan, but it’s clear whom she adores.

Ratmansky has created fine, fluttery, clustering dances for the firebirds; robust ones for a band of village gypsies; and ebbing and flowing ones for the sea creatures. These last wear upside-down images of their faces on the bodices of their costumes, and as the lights fade on their scene, they’re kneeling in tiers, forming one big cresting and subsiding wave. The pretty Princess of the Sea (Anastasia Petushkova) is herself a study in undulation.

The Met audience was peppered with children, but Ratmansky’s The Little Humpbacked Horse made people of all ages giddy with joy. Splendid dancing, magic adventures, a happy ending—all delivered without phoniness, flim-flam, or condescension.

Forget arguing. We’re lucky there are enough Ratmansky ballets to go around. And there’s rarely a dud among them.

What can be better on a gray afternoon than to read a serious review that makes you laugh? I’m referring specifically to Anna Karenina, based apparently very loosely on a novel I reread every five years or so. With tongue in cheek, I would submit, however, that the confusion of characters and the difficulty in identifying them in Ratmansky’s ballet could conceivably be interpreted as a statement by the choreographer about the difficulties in doing the same thing while reading any novel by Tolstoy.

We see very few Ratmansky ballets on the west coast, although the extremely Chekovian solo he made for Baryshnikov–which I loved–was performed here a couple of years ago. I’m eager to see his Don Quixote, which Pacific Northwest Ballet will perform next Feburary I believe. Thank you Deborah; I needed a laugh, as well as enlightenment today.

Great review! And so true about Ratmansky’s attention to background details. You can actually see a beautiful version of his Don Q (the same one that PNB will be performing next year) on iTunes right now, performed by Dutch National Ballet and starring Anna Tsygankova and Matthew Golding. It is available for download/stream in high definition here: http://tendu.tv/film/don-quichot/