The sixth movement of Olivier Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphonie presents an interesting lesson in melody, harmony and scoring, if we can step beyond the usual comments on birdsong, modes of limited transposition and the Ondes Martenot – important topics that are easy to write about but fall short of getting at a central essence of this musical experience.

Taken alone, the melody has a 1940s pop swing to it (sorry the images are blurry — click on them and they open clearly in a new window):

With a pop harmonization, we could easily have a suitable framework for a Rogers/Astaire dance number:

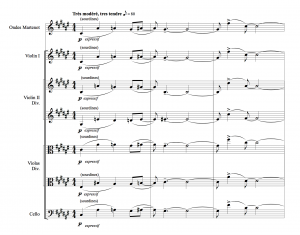

But Messiaen has a different goal in mind. His harmonization looks like this:

Phrase endings match the pop style, but chords through the middle of the phrase are completely irrational, giving an impression of randomness. And the way these harmonies are voiced makes them seem even more chaotic:

Note that the melody is doubled an octave below (difficult to see in these tight formations, and with these spellings), and no matter how complex the phrases get, they all end with clear, traditional cadences.

What is Messiaen after here? If we look at how the melody and harmony are arranged in the orchestra, an answer emerges:

First, the tempo: though it’s marked “moderate,” the eighth-note gets the beat, so each measure lasts six seconds. At that tempo, this melody is drawn out, distended, almost unrecognizable as a single unit as opposed to a series of melodic gestures.

The Ondes Martenot, with its unfamiliar (orchestrally speaking) sound, is marked f, clearly distinguishing it from the strings, marked p and muted. But look more closely: it’s doubled not only by the entire first violin section but also by half of the violas and the entire cello section an octave below. That’s an enormous body of support, held back by mute and dynamic. The strange harmonies, meanwhile, are relegated to dramatically smaller forces: the divided second violins and half the violas. So we have a melody with tremendous heft (though not loud), and harmonies that barely register in comparison. Now we see those irrational harmonies the way Messiaen intended them: an indistinct haze, wisps within the melody, like music we barely hear and misconstrue.

Turangalîla is Messaien’s take on Tristan and Isolde: when asked about the work, he replied simply, “it’s a love song.” Jardin du sommeil d’amour depicts the lovers enclosed in sleep with one another, a dream-landscape growing out of their slumber. I like to think of the composer enfolded in the arms of his love, Yvonne Loriod, in a Paris apartment, faintly registering a pop song on the radio from an adjacent flat mingled with bird song through the window. The distortions of the music, with foregrounded melody, distorted harmony and lethargic tempo, all conjure a surreal landscape: consciousness mingling with imagination.

The technique of slowing music down and exploring the details that emerge has an interesting contemporary resonance: current software has suddenly given this technique widespread currency, from Ted Hearne’s Law of Mosaics, which slows and overlays Barber’s Adagio for Strings and Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, to Justin Biebers U Smile subjected to 800% slowdown through PaulStretch. It’s a musical experience that finds a fresh intersection between Minimalism and timbral exploration — and Messiaen produced one of its more potent ancestors.