My colleagues and I taught a seminar on writing for piano last Friday. Referencing a wide range of thinking going all the way back to Cristofori, we focused mainly on innovations of High Modernism to the present. High Modernism came in the form of Webern, Copland, Sessions and Boulez, which established our baseline. From there we looked at Crumb, Ligeti and beyond.

My colleagues and I taught a seminar on writing for piano last Friday. Referencing a wide range of thinking going all the way back to Cristofori, we focused mainly on innovations of High Modernism to the present. High Modernism came in the form of Webern, Copland, Sessions and Boulez, which established our baseline. From there we looked at Crumb, Ligeti and beyond.

Over the course of this fascinating excursion, a thought began to formulate in my mind that I was only able to articulate very sketchily, but which has gradually coalesced over the ensuing days. Here it is: when we speak of a composer as someone who writes very effectively for an instrument, we sometimes fail to acknowledge that the composer has formed a deeply personal relationship with that instrument. Sometimes that relationship comes as a result of playing the instrument, but it can also be a result of long, intensive, up-close study: an engagement with the repertoire, the physicality, and even the virtuosi of that instrument. As a result, though we can list the techniques that we can steal from other composers for our own use, there really is no shortcut to great, idiomatic writing. As with any deep relationship, an enormous investment of time and energy is required. Without it, a composition can run the risk of sounding like a list of techniques, as opposed to a deeply experienced artistic statement.

We can make this assertion about any instrument, not just piano, even instruments of very recent technological vintage.

In keeping with this notion, I showed a new piece of mine called Honey to the students, focusing on aspects of the piano that speak most powerfully to me, after a lifetime of engagement with the instrument. Here they are, in no particular order:

- Time. Time is, of course, one of music’s most fascinating parameters, and the ability of music to influence the listener’s perception of time is unlike that of any other art form. The piano puts one player in charge of so many musical parameters, giving us the opportunity to bend time in several directions at once while maintaining overall coherence. Of course, one can do this with ensembles to an even greater degree, but the logistics become more difficult to surmount with the increase in numbers of players.

- Halo effect. The pedal can create an elusive halo effect around individual notes that is difficult to notate with any clarity but is always available to color a given passage. As a side note, I used to be more exacting with my pedaling notation, but experience has convinced me that pedaling is an area where precision is not necessarily a good thing. Ultimately, the pedal is not an on-off switch. Now I indicate pedal down or up only when I am absolutely sure it is the right thing. In this instance, I prefer to indicate how the music should sound, rather than how it should be played.

- Clarity and delicacy of high notes. The piano’s highest register occupies a region few other acoustic instruments can visit, and even fewer can match the piano’s ability to play high notes at a very low dynamic and yet have them sound with great clarity.

- Decay. Much can be said about the specific ways that struck notes on a piano decay, but I will say just this: everything around us will eventually fade away, a fact that we all bear with varying degrees of emotional response. I find the way sound decays to be one of the most powerfully expressive elements of music. The ability of the piano to layer many decays on top of one another can be dizzying, exhilarating and sometimes a little frightening.

- Distant Dissonance. The enormous range of the piano, coupled with the integrity of its timbre from bottom to top, allow for fun acoustic effects. Play a tune in parallel minor seconds, and the dissonance leaps off the strings. Play the same tune in parallel 37ths (geeky term for 5 octaves and a step) and the effect is no longer dissonance, but a lively coalescence.

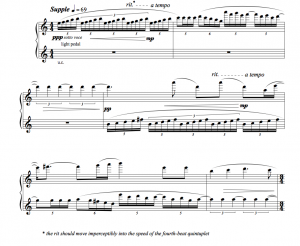

On the subject of time, here is an example of what I am talking about. The opening passage of Honey features a nested quintuplet that morphs into a regular quintuplet, in bar one. Clear enough, as far as these things go, but as more voices are added (bar 3 and beyond) this gesture becomes increasingly challenging to pull off. It’s a risky proposition for an ensemble, but not so much for a soloist. See below, and listen to the recording (Elixir, with pianist Yael Manor – check your favorite online music resource).