A quarter century ago, a New England journalist named Milton Moore turned me – a lover of rock and jazz without much interest in music before Elvis Presley and Charlie Parker – on to Schubert, late Beethoven, and The Well-Tempered Clavier.

Milton, who has been reviewing music, classical and otherwise, since the ‘70s, today starts a more-or-less monthly column about contemporary and “alternative” classical music. At least for the first few installments, he will be concentrating on composers whose work deserves more attention. His first installment is on the music of Valentin Silvestrov.

* * *

You’re sure to find a comfortable spot to nestle into the sprawling body of work by Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov. His compositions range from the conventionally outrageous to the outrageously conventional, and few composers today write with more transporting and direct lyricism.

The 81-year-old Silvestrov has published more than 100 works, including 28 for orchestra (six symphonies), 20 chamber works, and song cycles, piano works and large choral works. More than 36 CDs of his works have been recorded, including nine on the irreplaceable ECM label.

Silvestrov was a mid-Sixties bad boy, much like Russia’s Alfred Schnitkke, writing spare, percussive, and antagonistic orchestral works that were suppressed in his own country while being praised in the West, his prickly Symphony No. 3 winning the 1967 Koussevitzky Prize.

Then, in the Seventies, Silvestrov changed. He began to write what he called “kitsch music.” Musicologist and composer Svetlana Savenko writes that Silvestrov coached his performers that “it should be played in a very tender and heartfelt way” and directed the baritone performing “Silent Songs” cycle “to sing as if singing to himself.” This calm and utterly introspective approach is hardly the stuff hits are made of, yet it is uniquely affecting.

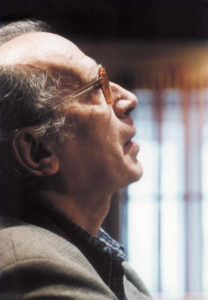

Robert Masotti/ECM

I can’t think of a living composer who writes more consistently entrancing songs and piano works spun of long, often indefinite melodic lines, dreamlike and drifting like watching smoke from a fire’s dying embers. He has titled several works as postludes, reflecting his elegiac and nostalgic sense that he stands amid the detritus of artistic eras. Alfred Schnittke surveyed that wreckage and despaired. Silvestrov instead sings hymns to it, hazy recollections of a reverence for the fading memories.

Henry James mused that as we think of our pasts, we do not recall events, but our memories of events, multilayered and changeable with each retrieval and each return to storage. So it is with Silvestrov’s nostalgia, his affection for nostalgia itself. Silvestrov shares with Schnittke a commitment to postmodernism, a belief that every musical inventor has expounded every musical concept for so many centuries that allegiance to any style is marginalizing. Schnittke called his approach “polystylism.” Silvestrov calls his “metamusic,” the cosmos of musical ideas.

In 1984, Schnittke famously wrote that learning Serialism was a rite of puberty for a young free thinker of the Sixties, “the unavoidable proof of masculinity through Serial self-denial.” He added, “Having arrived at that final station, I decided to get off the already overcrowded train. Since then, I have tried to proceed on foot.” Silvestrov rephrased the same sentiment: “The most important lesson of the avant-garde was to be free of all preconceived ideas – particularly those of the avant-garde.”

Silvestrov’s avant garde period is not to be dismissed. From it evolved his grand symphonies – Nos. Four to Eight – that are vaster, with denser orchestration and more obvious thematic cores than his Third. Each of these rich sonic events opens with a dissonant catastrophe and spans one long arc, each drama opening as if at the conclusion, the smoking rubble of a ruined soundscape, ominous and uneasy. From these growling sonic tectonic plates, haunting melodic motifs rise and sink back into the mass. His Fifth Symphony is the finest of the lot, its melodic motifs that rise from darkness in low brass stirringly Wagnerian in both character and soaring reach.

But it is Silvestrov’s song cycles and piano works, his kitsch, that I return to again and again. His “Silent Songs” were the first in this series of simple works that have that Schubertian ability to distort time. You find yourself holding your breath. Even his most direct melodies are fleeting, as if glimpsed from a train window. British critic Malcolm MacDonald wrote that Silvestrov writes not the lament itself “but the lingering memory of it.”

To sample this music, I suggest three discs.

First, the song disc “Stufen” with pianist Alexei Lubimov and mezzo Jana Ivanilova, on the hard to find Megadisc label that can be streamed for pay at Amazon or free at Spotify, settings of poetry from the likes of Keats and Pushkin. The echoing sonic ambience adds a shimmering haze to the nostalgia, a disc so intimate the listener feels almost an eavesdropper, as you can hear on “Elegy.”

And second, “Nostalghia” itself, a disc of piano works on the Hänssler Classic label recorded by the wonderful Jenny Lin (she of that insightful and fresh 2007 Shostakovich preludes and fugues). Lin is unhurried and luxurious in her phrasing, whether in the halting reverie of the title track, the haunting slow movement from Piano Sonata No. 1, or the three sweet tributes to the Serialists, that make you wish the Serialists themselves had such heart and sensitivity. The unabashedly Classical “The Messenger” for solo piano might seem a parody, were it not so utterly pleasing.

And second, “Nostalghia” itself, a disc of piano works on the Hänssler Classic label recorded by the wonderful Jenny Lin (she of that insightful and fresh 2007 Shostakovich preludes and fugues). Lin is unhurried and luxurious in her phrasing, whether in the halting reverie of the title track, the haunting slow movement from Piano Sonata No. 1, or the three sweet tributes to the Serialists, that make you wish the Serialists themselves had such heart and sensitivity. The unabashedly Classical “The Messenger” for solo piano might seem a parody, were it not so utterly pleasing.

In recent years, Silvestrov has expanded his sonic scale with choral compositions rooted in Orthodox tradition and advancing the composer’s gift for achingly evanescent melodic constructs. ECM has released a pair of recordings with Mykola Hobdych leading the Kiev Chamber Choir in these a cappella gems, the first of which BBC critic Michael Quinn called simply “ravishing.” Sample the Ave Maria, you’ll agree.

Silvestrov’s music could be grouped with Pärt and Górecki, but that misrepresents his unique approach to melody. He is far less given to minimalist sequencing than these other Eastern mystics. Silvestrov’s music is perhaps anachronistic, but the question isn’t, why do we need more traditionally beautiful tonal music? The question should be, why would you turn away from this?

– Milton Moore