[contextly_auto_sidebar]

Though he’s hardly a household name, North Carolina’s Chris Stamey has been just alongside many of the key developments in left-of-the-dial rock music over the last four decades. As a young Southerner he visited and then moved to New York City right as CBGB’s and Television were exploding, he helped found the dBs and Let’s Active, which put him on on the ground floor of the Southern pop movement that produced R.E.M.

has been just alongside many of the key developments in left-of-the-dial rock music over the last four decades. As a young Southerner he visited and then moved to New York City right as CBGB’s and Television were exploding, he helped found the dBs and Let’s Active, which put him on on the ground floor of the Southern pop movement that produced R.E.M.

Stamey played for a while with Big Star’s Alex Chilton, later produced Ryan Adams’ old group Whiskeytown, riot grrrl trio Le Tigre, and Texas troubadour Alejandro Escovedo. He’s also had a busy solo career, and collaborated now and again with fellow dB Peter Holsapple.

I was pleased and curious when I heard that Stamey had a memoir coming: In 1992 I moved to Chapel Hill, NC, to go to graduate school, right around the time he was landing back in his native state after years in New York. Stamey and his acoustic guitar were frequent sites on Franklin streets and the coffee houses there; I saw him play numerous times, a friend and I often shouting a request for September Gurls.

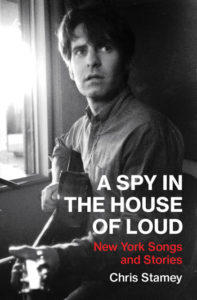

Still, I was surprised at how smartly and incisively written the ensuing book, A Spy In The House of Loud (subtitled New York Songs and Stories) ended up being. (Angelenos: Stamey will be at Book Soup Saturday June 9 and at The Federal Bar/NoHo Sunday morning; both involve musical performance. Full tour schedule here.)

What follows is my exchange with Stamey via email.

Give us a sense of the radicalism of the music happening in New York in 1975: You arrived for a visit, as a very young man, just as CBGB’s was starting to rage and right before the release of Television’s Little Johnny Jewel single. How did the best of that music break from American rock at the time, including what you were hearing around in ’70s North Carolina?

Some of the music at and around CBGB stretched arms out to the past: the music of both Blondie and the Ramones referenced 60s rock, Spector and Leiber and Stoller girl-group chords and chipper melodies and sometimes even the baion beat, just played faster and louder, and without the strings. In doing so, they sailed right over the 70s arena pomp and cornball theatrics, as if it had never happened. (The New York Dolls, a bit earlier, had been a gateway to these attitudes.)

In those years I was much more captivated by Television, however, who had roots both in free jazz and the Romantic “classical” tradition, musically, and in the French Expressionist poetry tradition, both lyrically and philosophically. They seemed to have very few antecedents in rock from the past, 70s or otherwise, and they worked really hard at it. I also heard, in their music, some of the “mid-century Modern” music techniques I’d been learning in music school, which I liked.

The Talking Heads, who followed on their heels and often played shows with them in the early days, also shared that “stench of the new,” bringing in elements of the visual art world and of dance grooves, trying to find a way to evolve and move the music forward with each album release.

All of these folks, including Patti Smith and Richard Hell, wanted something new, felt that a palace revolution was immediately necessary, that there must be something better out there to find.

When you formed the dBs, were you conscious of going against the grain of the musical mainstream? What it was like to form an indie band in that time and place, and what were you and the rest aiming for?

Although the dB’s was formed by accident — Gene Holder and Will Rigby joining me “temporarily” to promote a song that Richard Lloyd and I had recorded/created without them — it persisted because we liked the way it sounded and liked hanging out with each other. It grew organically, and then exponentially when Peter Holsapple came up to join us. We’d been in so many bands in NC, for the last decade, including Sneakers (me and Will), and they were I guess all “indie bands.” So this was part of that continuum.

We were aiming just to find out what we were about, in the laboratory setting of late-nights in clubs and long days in rehearsal. But I think songwriting was key — both Peter and I wanted to bring a new song into rehearsal and then bask in the glow if it caught fire with the quartet. And when that would happen, it’d be a great incentive to do it again. Any kind of larger cultural recognition seemed pretty remote, frankly, when the band formed.

This book is extremely well written, with a strong writer’s voice, nicely drawn scenes, a sense of history, and so on. It’s kind of impossible to know for sure, but do you have a sense of how you learned to write – what books or ideas or experiences guided you to be able to do this?

Thanks for saying this! I never had any creative writing classes, or even any post-high-school English education. I did have some philosophy classes in college, and from that learned that it’s possible to be precise, that a sentence could be a kind of math, an equation that is either true or false. Of course, it’s hard to always hold to that standard, especially when writing about something that sweeps you away, but I keep trying. I don’t kid myself: I’ve got a long ways to go, it’s a struggle. (Both Will Rigby and Peter Holsapple, from the dB’s, are good writers, fyi. Peter had some J-school experience, like you did.) Right now, I’m reading The Elements of Style, slowly and carefully; too bad I didn’t do this before writing the book. With music and recording, I’ve generally found that I learn faster by jumping off into the deep end, and this first attempt at writing was also a “sink or swim” educational process.

I do have to recommend Betty Edwards’s Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain as a good book for songwriters and writers in general. I enjoyed writing the “radio musical” Occasional Shivers last year (a podcast available for free on iTunes) and I’m currently writing the sequel to this, for actual theaters this time. It’s set in Philadelphia and tentatively entitled Give My Regards to Off-Broadway (Remember Me to Rittenhouse Square). And I’m also barely into writing a short novel, called The Dad Joke Club.

What are your favorite books about music – memoirs, criticism, Mystery Train-like cultural histories, etc.? Were any of them a model for your book?

I have checked out a lot of music memoirs from the public library in the last decade, reading them in fits and starts before falling asleep at night, and from them I took what I didn’t want to do — be boring for long stretches, settle scores, etc. I did not think of my book as a memoir, though, when I was writing it, and it’s still the case that it’s not really about me as much as about my songs . . . and others’. (In fact, a book about me would be quite different.)

I thought of it as a book about songwriting, in a way: I wanted to communicate some of the excitement I found in different kinds of music, and then to explore what made it exciting for me. And I wanted to find things that might put someone in the mood to put the book down and go create, in the same way that Barry Miles’s book with Paul McCartney, Many Years from Now, did for me on occasion. Now, after a while, as happens with any creative effort, my preconceptions fell to the side and I just “followed my nose.”

You’ve worked in all kinds of settings – as a member of bands, as a solo artist, as a producer for Whiskeytown, Le Tigre, Alejando Escovedo and others. I’m wondering what you’ve learned about group dynamics, that invisible chemistry that make some arrangements of musicians really fruitful and others sort of flat. Any rules of thumb?

Hmm. Musicians lead complicated, demanding lives, but if the music they are making is itself inspiring to them, then optimism and joy follow from this. Musicians are doing what they do because they respond strongly to music. So if I can clear away cobwebs and weeds (in arrangements, lyrics, key choices, tempos, instrumentation), ideally with a minimum of changes, and let the goodness of their music shine forth more clearly, this in itself lifts all our spirits. And then the “chemistry” of the band and the project jells.

One of my private rules, when producing, is “Don’t think you are right, just because you are experienced.” I try to put away my expert mind, to be alert to what might be new and unique about what they are doing, what they are saying. This is hard for me, sometimes, but it’s important to do. I also think of myself as a “music producer” more than as a “record producer.”

It’s amazing how many good and great bands – the backbone of the U.S. alternative and indie-rock movements — have come out of Southern college towns, especially Chapel Hill and Athens. (We can credit Charlottesville, at least in part, for Pavement, as well.) Do you have any hunch why?

I am not sure why. I think that songwriting requires some time alone, and maybe there is more space in the South, the hive is less tightly packed, easier to find solitude? Cheaper rents, older, vibey buildings?

As far as the college part: It’s life cycle — high school days are times when puberty is especially clouding and intoxicating the brain, then in college years those clouds are slowly clearing and a new, strange “adult” landscape appears and has to be deciphered, during a time when a university environment typically encourages inquisitiveness. And music is a way to talk to your peers about what you are finding, post transformation? In the holding tank of the university?

But I really don’t know. In the Preface of my book, I quote Chilton as saying, “Good things come from the provinces,” and there is something to that, apparently.