IT’S hard to think of a figure in American cultural history more complex and protean than Leonard Bernstein. For my generation, he was already in eclipse when we came of age in the ’70s and ’80s. But he was such a titan that many of us — and those older and younger — are looking forward to the performances of his work and the upcoming exhibit at the Skirball Cultural Center here in Los Angeles. (I have a modest piece about the show and Bernstein’s legacy in Los Angeles magazine, here.)

In any case, CultureCrash’s guest columnist remembers the Broadway roots of the film West Side Story, and has this to say about the forces that made it all possible.

By Lawrence Christon

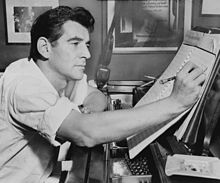

This centennial year of all things Lenny rightfully celebrates the career of composer-symphonic conductor-pianist-TV educator-author-activist and international celebrity (gasp) Leonard Bernstein in numerous orchestral settings and FM classical music airplay. But Bernstein was a born showman too, and it’s a shame that we’re not hearing more of the works, however sparse his output, that put him in the top rank of Broadway composers.

Broadway was the itch he loved to scratch. On the Town (1944) is full of the madcap zest of three young swabbies out to devour every ounce of life they can on 24-hour liberty in New York City before they have to return to their ship and a world war whose outcome is far from assured. The Bernstein score, with Comden & Green lyrics and libretto, contains songs that went on to lives of their own, such as “New York, New York,” “Lucky To Be Me,” and “Lonely Town”—loneliness an emotion you’d never think the lavishly extroverted Bernstein experienced.

He traveled internationally, conducting Mozart, Beethoven, Mahler, Schubert and other giants of the Western canon. But New York was his town. He found all the violent, corrupt, stark, romantic, spiky, yearning and anxious impulses of the post-war world in its streets and alleys (his powerful score for the 1955 film, On the Waterfront, is fearsome and riveting). He was one of the figures who made New York the cultural capital of the West through the ‘50s.

West Side Story represents one of the decade’s culminating works. A lot of people consider it the only American musical besides Porgy and Bess to qualify as an opera (I would add Stephen Sondeim’s Sweeney Todd to that category). There’s a good case for it, especially if you consider how far beyond the standard boy-meets-girl (or more recently, boy-meets-boy) Broadway terrain the show travels. As a rule, musicals tend to be about ironing out misunderstandings. They don’t usually erupt in violence and bloodshed. They don’t show people stuck in intractable hatred and dead-end lives. They don’t end in a funeral march. And they are rarely as heart-wrenchingly beautiful.

West Side Story opened at the Winter Garden Theatre on September 26, 1957, and was a smashing success that seemed to tap flashpoint tensions between Puerto Ricans and Anglos that had been simmering for years. It was also the first musical, maybe the first Broadway stage piece of any sort, to deal with what today would be called disaffected youth but was then termed juvenile delinquency.

Its arrival had been a long time coming, as Bernstein and playwright Arthur Laurents periodically met with choreographer Jerome Robbins in the late ‘40s to flesh out Robbins’ idea to develop a New York story out of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Robbins and Bernstein had worked brilliantly together before in On the Town and Fancy Free, and enjoyed a creative marriage famously made in both heaven and hell. An early version depicted Jews having it out with Polish-Italian Catholics in lower Manhattan. Scheduling conflicts and availability kept the three from meeting in earnest, and by the time they did, the look and sound of New York, indeed the nation, had begun to show a Latin flair.

West Side Story is mostly Robbins’ baby (he directed as well as choreographed), but with the addition of Stephen Sondheim as lyricist, this became one of those collaborations in which each partner’s contribution is utterly essential.

Bernstein was the one who got it right away. His no-nonsense prologue, consisting of a brassy pair of terse three-note phrases, sounds like a blunt call-out to rumble followed by a nervous, agitated prelude to something awful and unavoidable. (Don’t listen to the movie overture, which like all overtures is designed to introduce the comfort of familiarity. West Side Story is not about comfort.) His orchestration (aided by Sid Ramin and Irwin Kostal) added conga and bongo drums, castanets, clavels, woodblocks and timbalis to Latinize the standard pit band of brass, strings and percussion. His contrapuntal use of tritones and diminished sevenths, among other devices, keep us unsettled, uncertain, in the dark about how things will play out. Robbins’ choreography followed suit, filled with the explosive energies of youth, sex and the proximity of violence.

One of the elements that make it work so well is that every song is indispensable to the development of the story and its characters; even “Gee, Officer Krupke,” as funny as it is (“I’m depraved on account of I’m deprived”) points to the awkwardness of social institutions dealing with kids who feel like outcasts, including Anglo kids. Virtually every other song follows the pulsing arc of youth’s innocence and ardor, and what happens when it runs into devastating tragedy. “Something’s Coming” is every young person’s breathless anticipation of a terrific life ahead. In “Maria,” the name of one’s first love is as sweeping as the horizon. “One Hand, One Heart” reveals us under the skin. After such a dazzling fearless beginning for Tony and Maria, Bernardo and Anita and the rest of the Jets and Sharks, everyone realizes at the end, in the funereal “Somewhere,” that there’s got to be a better place than the ghastly one they’re in now. The aria duet, “A Boy Like That,” rises to a shattering pitch that reminds us how song erupts when emotional intensity is too great for any other kind of expression.

That production won three Tonys and numerous other awards in subsequent revivals. The 1961 film won ten Oscars, including Best Picture, even though its overblown production values snuffed out the play’s sizzle. Bernstein resented the bloat added to his score, which he and reshaped into a symphonic suite that’s now a staple with conductors everywhere, and a favorite of our latest young titan of the podium, Gustavo Dudamel.

Robbins’ contribution is less vividly remembered because dance is so evanescent—it ends with its own movement, and you can’t retrieve it through an earbud. Bernstein’s lyrical passion informed “West Side Story’s” troubled soul, as his passion informed virtually everything he did. He was uncorrupted by irony. The exuberant variety of his life and talents has made us all the richer.

A centennial exhibit on the life and work of Leonard Bernstein opens at the Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles, on April 26