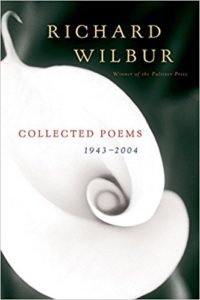

JUST a quick post to note the death of the great poet and translator Richard Wilbur. Until two days ago, when he passed away at 96, I would have called him America’s finest living poet.

Like most kids, I studied some poetry in high school and college — Eliot, Auden, Yeats, Langston Hughes, Bishop, etc. I even, in my very early 20s, fell hard for a few poets in translation (Rilke and Neruda, I think.) But it was not until a few years later that I came to see that there had been poetry, in English, in my lifetime, that was stirring, witty, accessible, and part of the tradition or traditions I was interested in.

And one of the key figures in the survival of American poetry into the end of the century was Richard Wilbur. Because he had taught at my alma mater for many years, albeit before I arrived, I’d known his name for a long time; he’d also been US Poet Laureate and won two Pulitzers. (A professor of mine from Wesleyan mentions that when he met the unfailingly gracious poet, in the 1970s, Wilbur already knew his verse, which was controlled and balanced and a bit formal, was already unfashionable among the late Confessionals, Boomer hippies and neo-Beats then dominating the poetry world, but didn’t gripe about it.)

But it was really only later, when I was out of school and looking for work that interested and excited me, than I got into his verse and that of a few of his contemporaries. When poet James Merrill — a longtime friend — died in the winter of 1995, I was the arts reporter at the local paper in shoreline Connecticut, and called Wilbur to discuss the work of his fellow Amherst graduate. Wilbur was helpful and eloquent, as well as shaken up by the sudden departure of a peer; I wish I still had the notes from that conversation.

When I wrote the book upon which this blog is based, Culture Crash, I wrote an extensive section on 19th century bohemianism — the clash of artists and art-making with the marketplace, on the final retreat of the aristocracy. Much of this was edited out of the finished book, but the poem that kept going through my mind was Baudelaire’s Albatross, and Wilbur’s wonderful translation of it. As a lover of French poetry who does not have any French, I have read A LOT of Baudelaire, and Wilbur’s Albatross, Correspondences (“Nature is a temple, whose living colonnades…”), and a few others are the best I know by an American. I found Wilbur’s mailing address and composed in my mind a letter to ask if I could reprint the poem in my book; but this was a letter never sent.

I’d suggest that if there is an established American poet who was a better translator of European poetry, I don’t know who it’d be.

One of the best books ever written on American poetry, Peter Davison’s The Fading Smile, about the post-Frost literary scene in ’50s Boston, has a very fine chapter on Wilbur. As a veteran of World War II’s European theater, who wrote to reinforce and celebrate a civilization he saw nearly destroyed by the Nazis, he was a bit unfashionable even then.

The Los Angeles poet Leslie Monsour posted the last stanza of the beautiful early Wilbur poem Juggler, and I will let this stand as nearly the last word for now. I won’t try to explain the thing but will just say it makes more sense in context:

If the juggler is tired now, if the broom stands

In the dust again, if the table starts to drop

Through the daily dark again, and though the plate

Lies flat on the table top,

For him we batter our hands

Who has won for once over the world’s weight.

Hoping to get some time later to write more on this titan of the world of letters.