[contextly_auto_sidebar]

Back in the mid-’80s, I was in a Calculus class when a friend I knew mostly from our shared love of punk rock handed me a hand-labelled cassette of a musician I’d never heard. When I got home, I played this selection of songs by Billy Bragg — A New England, Greetings to the New Brunette, It Says Here — which reminded me of the Clash in their political force and Dylan a bit in their stripped-down format — just a mouthy singer, alone with his guitar — but defined its own ground.

Seeing Bragg play at the “old” 930 Club in Washington, DC became one of my first regular musical pilgrimages; this and annual trips to see a New Jersey band called The Feelies became key imprinting events of my teenage years.

Flash back several decades, to the years after World War II in Britain. A nation still reeling from the war, where many consumer goods were still rationed, discovers America through the music of Leadbelly and New Orleans jazz. The result is called skiffle, and it will hit a brief and stylistically limited peak but serve as a foundation for the Stones, the Beatles, BritFolk and psych musician like Bert Jansch, Zeppelin, and David Bowie.

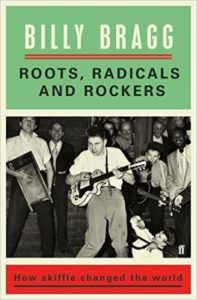

Tonight, 10 Oct, Bragg speaks on his excellent new book Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, at the Grammy Museum. (Tomorrow,11 Oct, he’ll perform at the legendary Troubadour with, presumably, some skiffle-inspired between-song banter.)

This is more than just a fan book written by a musician, and more than just a book about music: It’s a full social history.

My conversation with Bragg is here, in the Los Angeles Review of Books.