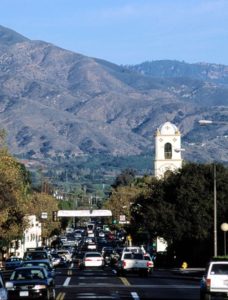

This year sees an unlikely but, I suspect, fortuitous paring: Pianist Vijay Iyer — one of the most inventive figures in jazz today — is curating the Ojai Music Festival, a friendly, mellow outdoor gathering dedicated to new, challenging, and rarely performed classical music. (The festival starts Thursday and runs through Sunday.)

Part of Iyer’s emphasis is presenting music by the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, a group of Chicago jazz figures founded in the ‘60s and dedicated to progressive racial politics and adventurous musical possibilities. (One of the AACM’s key members, Anthony Braxton, taught a jazz history class I was lucky enough to take, many years ago.)

Your humble blogger has visited Ojai, on and off, for two decades now, but for complicated reasons, I’ve not been for three years. So I’m very much looking forward to what elapses this weekend.

What follows is my phone conversation with Iyer, who lives in New York City and teaches at Harvard University.

So you’re a bit of an atypical choice to helm the Ojai Festival; you’re best known as a jazz pianist. On the other hand, you make perfect sense, since the festival has been defined by a kind of eclecticism. How do you see yourself fitting into what Ojai has done over the years.

I don’t really feel pressured to fit in — I’m just doing what I like to do. I’ve brought a lot of my friends along, people I respect, artists whom I trust. That’s really all there is to it.

As you say, I’m best known as a jazz pianist, but nobody is one thing, really. Especially not today.

Did you grow up with classical music? And whenever it hit you, who were the first composers or styles that knocked you out?

Well i don’t really believe in styles. I think styles are fictional unities and ways of stereotyping about people. So i don’t find that a useful concept or approach.

But i grew up playing music in two very different ways. One was that I started Western classical violin lessons at three, and continued that for 15 years — in orchestras, playing solo repertoire, in chamber groups. So a lot of different things.

Did it feel like something for your parents sake or something you got into at some point?

I think what energized me about it was playing in ensembles, playing with people. The way you study, and in private lessons the emphasis is solo repertoire, perfecting  these pieces that have been played millions of times by other people.

these pieces that have been played millions of times by other people.

But the second parallel track, when I was growing up, was that I played piano by ear, at the same time, so i was always improvising at the piano, picking out melodies, and figuring things out and just screwing around basically, on the piano. That eventually developed in a very different way, in a different musical sensibility that was in contrast to my training on the violin.

The music that impacted me when I was about five. I also remember listening to the soundtrack for Saturday Night Fever — that record, when it came out… And I was very into Michael Jackson and Prince, the Police…

Then when I was in high school I became more aware of the African-American composers and improvisers associated with the word “jazz,” started delving into that more seriously. We had a very good jazz ensemble at my high school: They let me in as a pianist and that let me study that musical language, that repertoire in more depth.

In the orchestras we played Rachmaninoff and Borodin and Smetana, a lot of Eastern European stuff. But then also Scandinavian — Sibelius — Brahms… I played concertos by Bruch, Saint-Saens… And I was also studying Thelonious Monk’s music, Duke Ellington’s music, Coltrane’s music, Randy Weston’s music, Andrew Hill, Alice Coltrane, Charlie Parker, a lot of stuff.

While Prince is on the radio around you…

I was a huge Prince fan from basically ’81 to the mid-‘90s; I was obsessed with his music. I saw him a few times; that really stuck with me.

Improvisation has been a part of classical music in the past, but it’s nowhere near as central to it now as it is to jazz. I wonder if you think classical music could be more robust and full of possibility if it restored that lineage that it’s mostly abandoned.

I’m not gonna advance any thesis like that. Because I don’t have any allegiance to a construct called classical music. Nor to a construct called jazz. I’ve been quoted by the Ojai press people as saying we should replace the idea of genres with  community. It’s not about styles, it’s about people, and what people find themselves doing over time…. If you treat it as a style that’s static and has issues with itself, as opposed to a community that evolves and interacts with other communities… Its borders are only as solid as they police themselves to be.

community. It’s not about styles, it’s about people, and what people find themselves doing over time…. If you treat it as a style that’s static and has issues with itself, as opposed to a community that evolves and interacts with other communities… Its borders are only as solid as they police themselves to be.

So when we think of it as a group of human beings working together, it’s got more of a sense of ethics and responsibility…. It’s about, What are people in that community looking to do today?

You say I seem like an outlier, but I think it’s part of a larger trend, in this system called classical music electing to create change.

I don’t know how it’s working elsewhere, but in the last few weeks I’ve been to the LA Phil for an Iceland Festival which included Sigur Ros and ended with this virtual-reality Bjork thing that was very cool; I saw Brooklyn Rider play new music at a hall in Beverly Hills, this summer at the Hollywood Bowl has several mergings of classical and indie rock… So I know its getting more eclectic around the edges. I wonder how representative of the larger world of classical music this is. I’m happy to see the fissures around the edges.

I guess the more interesting question to me is, What kind of sense of resp onsibility does that classical music community feel toward artists of color, music made by people of color in the West, especially people of African descent in the West. Because for a long time, the term classical music has been a code word for whiteness, for music and art and people of European descent. And it’s been willfully and persistently excluding anyone else from that category. So this is the peril we encounter when we talk about stylistic eclecticism — we’re not talking about people. I’m interested in, What is the music doing? And who is it doing it for?

onsibility does that classical music community feel toward artists of color, music made by people of color in the West, especially people of African descent in the West. Because for a long time, the term classical music has been a code word for whiteness, for music and art and people of European descent. And it’s been willfully and persistently excluding anyone else from that category. So this is the peril we encounter when we talk about stylistic eclecticism — we’re not talking about people. I’m interested in, What is the music doing? And who is it doing it for?

You have at least a few events dedicated to the AACM, including a piece by Anthony Braxton. What makes that era, that movement important to you?

When I think of the questions we’re addressing here, I realize, there’s a legacy of people addressing these questions for half a century. And they picked up where others left off. So Braxton, Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, Wadada Leo Smith, George Lewis, and a younger generation… And George Lewis’ opera is about the AACM — it’s about a collective of musicians on the segregated South side of Chicago, who decide to create a new world for themselves, in the music that it’s portraying. That music creates its own historical trajectory. And I’ve been mentored by all of these people.

Over the two years that we took programming this thing — Tom Morris and I — there was a mutual interest in shining a light on that body of work, that body of artists. And continuing their presence in the festival — George Lewis’s music has been performed at the festival before.

Those artists paved the way for what I do; they created the reality that I exist in, to put it bluntly.