ONE of my favorite writers in any genre is the USC humanities professor Leo Braudy, justly celebrated for his Frenzy of Renown, a history of fame going back to Alexander the Great. Braudy writes widely on literature, film, ancient civilizations. the question of America, the overlap of culture and politics, and all kinds of subjects that interest me. He’s insightful, sometimes inspired, and always accessible to the educated non-specialists. (I wish there were more scholarly writers like him.)

Braudy’s latest book is “Haunted: On Ghosts, Witches, Vampires, Zombies, and Other Monsters of the Natural and Supernatural Worlds.” (The book is on Yale University Press, the publisher of Culture Crash, but I was on record as a fan of Braudy’s before he had the good sense to move to Yale.) In any case, the book is a blast.

What follows is my correspondence with Braudy. Hope readers enjoy it as much as I did.

Q: You’ve tracked the way fear has exerted itself in Western culture from early-modern to contemporary times. But to what extend are fear and terror — and their associated gallery of imagery and narrative — simply a part of human nature? That is, would any culture or any historical (or even pre-historical) time period work the same way, but perhaps with the details changed?

A: Human nature to me is a very ambiguous and frequently changing concept. Yes, we have desires, hopes, and fears that seem innate and timeless, but their expression is shaped by the specific personal and public contexts in which they appear, and so they mutate or at least change in relation to our own biographies and what’s happening around us. By the same token, the expressions of the fears and anxieties of large groups of people are conditioned by the historical times in which they emerge. “Human nature” may be the bricks and mortar, but many different buildings can be created from them. Such a perspective would work in any time period, but the change in the details is exactly the crucial distinction between one era and another. Early on in my literary work I became fascinated by the way emotion tended to be written out of literary and cultural analysis in favor of seemingly more tangible factors like politics and economics and, in the discussion of literature especially, the dictionary meaning of the words in the text. To a certain extent this is the result of the influence of the Marxist distinction between base and superstructure: art in this view is “soft” superstructure, while the “hard” facts of economics are the base and therefore the reality of what is happening or has happened. So the critic uses political and economic facts to “explain” artistic production. I would reverse that formulation, or at least readjust the balance: art embodies a history of emotion that helps determine how history’s otherwise external facts develop and how people respond to them.

The years around the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution — both late 18th century but bleeding into the “long 19th” — produced a large and acute batch of fearful imagery. Why was that, and what kind of literary/ cultural/ psychic terror did it produce?

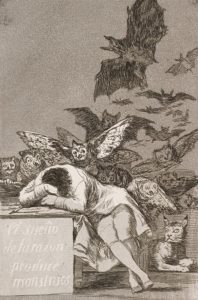

The great battle cry of the American and French revolutions was the future: throw off the inherited structures of past tyranny like monarchy and religion and move triumphantly forward to liberty. The Industrial Revolution similarly promised a new sense of individual and collective will; human intelligence would master the repressions of environment and nature: turning rivers into power, replacing individual craftsmen and their unique products with a production line of interchangeable parts that could afford similar quality at much lower cost, etc. So far, so good. But in the process, as in all revolutions, whether technological, economic, or political, the broad brush of change swept aside things of value as well. The rise during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries of gothic literature, painting, and even music that drew upon the supernatural expressed something of the fears of what change had brought, the dark recesses from which monsters emerged.

It sorta makes sense now that Poe invented not only the horror story as well as the detective tale, eh? How are they related?

Some reviewers of Haunted have been puzzled by my inclusion of a chapter on the detective in what is otherwise a book about horror, but to me the monster and the detective are opposite sides of the same coin: the monster the figure of disorder and fear, the detective the seeker for order and reason. That Poe wrote masterpieces in both forms shows their basic dependence on one another, their Jekyll and Hyde-like interaction. Poe didn’t invent the horror story, but his poems, short stories, and longer works arrive in the 1830s and 1840s at a crucial moment. The literature of fear had become a widespread and recognizable genre in England, Europe, and America. To that literature he contributed an intensified version of the first-person narrator (in, say, “Fall of the House of Usher” and “William Wilson”) as well as a self-conscious sense of the supernatural mystery that cannot finally be solved that had a lasting influence on both American and (through Baudelaire) French literature. At the same time the growth of police forces and the arrival of an embryonic crime-solving force in places like the French Sûreté and Scotland Yard offered the possibility that in fact crimes could be solved. Poe’s detective C. Auguste Dupin is, however, not a member of any official police force. As an outsider he has the detachment to mingle reason with a powerful instinct in what Poe called ratiocination, along with a compatibility with the criminal mind, in order to solve his cases. In Poe’s work this combat between the empirical idea that facts will be decisive and the supernatural idea that there are things in the universe we can never know fully is a primary engine of his creativity.

In your book’s opening pages you describe your ambition to write the history of an emotion. Is that difficult to do, intellectually? And is that unconventional way of looking at culture a difficult fit in contemporary academia, including academic presses? Would it be possible without Freud?

I don’t count Freud as a particularly good guide to the understanding of how emotion might have a history, since his theory of the relation of the self to society depends so much on the repression of emotion and inner conflict. In many ways I prefer the point of view of Carl Jung, who explored the way in which the repression of emotion created the monstrous inner self, which without that repression could become vital and creative. This isn’t quite the 60s ‘do your own thing’ or ‘let it all hang out,’ but a recognition that consciousness and rationality have to come to terms with the powers of the unconscious and the emotions. (I’ll leave aside for now Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious, which is a whole other issue.) There’s a great scene in Rouben Mamoulian’s version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in which Hyde is pleading with Lanyon to give him the chemicals he needs to turn back into Jekyll. Between them on the wall is a large portrait of Queen Victoria. In other words, if Jekyll hadn’t lived in that era or if he hadn’t taken its repressions so to heart, would Hyde have existed?

How have some images from literature and art — originating perhaps as far back as the Reformation — transmuted themselves into recent popular culture?

Even before the Reformation, religious imagery struggled to present images of both the divine and the diabolical. The earliest images of Jesus, say, were of a young man with curly hair and a lamb over his shoulders—the Good Shepherd of the Gospels as well as a figure out of Greek and Roman pastoral. Satan as well changed his image from being a member of God’s court (in the Book of Job) to the competitor with Jesus for God’s favor to the embodiment of the principle of evil. In religiously oriented horror films that literary and visual history helps create the figures we see, with of course some allowance for the nuances of contemporary creativity on the part of the production designer and the makeup person. The point to remember is that visual representation has its own demands, which may be different from those of literary description. Dracula on film looks little like Dracula in the novel. Sherlock Holmes in the stories and novels never wore a deerstalker hat or smoked a Meerschaum pipe.

Your writing — like Morris Dickstein’s and a few others — reminds me a bit of the generation of Leslie Fiedler and Irving Howe. Do you feel an affinity with that crew?

Morris was a year ahead of me in graduate school at Yale. Yale at that time was not yet the home of Paul De Man’s deconstruction or Harold Bloom’s Romanticism. It was still under the aegis of the New Critics like Cleanth Brooks and William Wimsatt, but I was more intrigued by teachers like Martin Price who were trying to see the main currents of an entire period. Fielder, who was then at SUNY-Buffalo, would be in the same category, especially with his willingness to see popular culture as significant as high culture (such outmoded terms) in understanding an era. At the time too I was more interested in distinguishing what I was doing from what others were doing, but in the long view there are definitively affinities, especially in the willingness to write for magazines and newspapers, otherwise condemned as “belletristic” by the more academically oriented. In high school my critical heroes had been writers like George Orwell and Edmund Wilson, along with the early film critics like Andrew Sarris, Pauline Kael, and Dwight Macdonald. I went to the movies all the time, so any exclusive focus on literature alone was out of the question. Later I took a job at Columbia, where Morris was also on the faculty. Lionel Trilling’s office was across the hall from mine, Edward Said’s down the hall, and the whole Columbia English faculty, as well as the context of New York City, strengthened my sense of the social role of art, the need to take not only the world in which it appeared but also its audience into consideration. Morris and I later co-edited a collection of essays on great film directors for Oxford. His first book, though, was on Keats, while mine was on the relation of history-writing to novels in the eighteenth century. Make of that what you will.

Thank you for being part of the CultureCrash

Interesting perspective – I will try to check out more from Breaudy. His comparison of Jung and Freud is much appreciated. Am wondering if he ever read any of Manny Farber’s film criticism. Farber was a unique voice and also a great painter.

I can’t imagine Braudy would have missed Farber’s film writing — those pieces have been issued at least twice in the 20 years I have been in LA, and Leo has been at this a lot longer than I have