[contextly_auto_sidebar]

I’M STILL LISTENING, MARLON

By Lawrence Christon

It doesn’t happen often because it can’t. The taste of the madeleine that unleashes a torrent of memories and associations, the thing that makes you stop what you’re doing and plunges you into unexpected reverie.

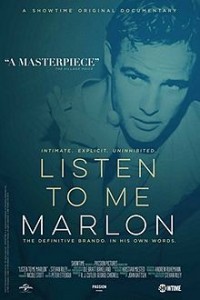

With me, it was hearing Marlon Brando’s voice, that strange, half-vaulted, pureed-through-the-sinuses sound that came alive at the beginning of Stevan Riley’s documentary, “Listen to Me, Marlon,” which came out in January. Based on audiotapes Brando made over the years as a kind of solo psychoanalysis, the film’s tabloid choices and sometime overstretched production values are nonetheless overpowered by the force of Brando’s reflective and arresting personality—very like so many of his films.

Based on audiotapes Brando made over the years as a kind of solo psychoanalysis, the film’s tabloid choices and sometime overstretched production values are nonetheless overpowered by the force of Brando’s reflective and arresting personality—very like so many of his films.

A lot of same-sounding adjectives and descriptions attach to him, like ‘brooding genius’ and ‘the greatest film actor ever.’ Certainly he shared the latter distinction, as far as the 20thcentury is concerned, with Laurence Olivier, who was, while more a stage performer, a completely different kind of actor, technical and virtuosic where Brando was intuitive and improvisational. But they both towered over their profession; at the top of their game, they were electrifying, unforgettable. With Brando however, the performance spilled out into the real world in unending examination that was just as enthralling.

One of the definitions of genius is that it changes what comes after. Amazingly, lot of people have already forgotten him. A writer friend of mine asked his new editorial assistant, a recent Ivy League grad, to check a reference on Brando, only to draw the response, “Who?” Which shows how hard it is for us to see, so much later, how Brando’s acting widened and intensified the possibilities of human expression.

It’s also the nature of genius to become diluted over time by copycat mannerisms as form adapts to the terms of initial discovery. In other words, eventually the thrill is gone. But no one who was around at the time can ever forget what it was like when he first hit. The shock of the new was more than unsettling, Budd Shulberg, who wrote the screenplay for one of Brando’s best film roles in “On the Waterfront,” remembered in a 2005 Vanity Fair article what it was like to see the 23-year-old in one of his best stage roles in Tennessee Williams’ “Streetcar Named Desire,”

“…Nothing will ever compare to the explosion set off by Brando in his savage portrayal of Stanley Kowalski, the brutal blue-collar tormentor of his defenseless sister-in-law, Blanche DuBois, who has come to take refuge with him and his wife. I will never forget the impact Brando had on me and the rest of the audience. This was a beyond a performance. What we were seeing was a new kind of visceral intensity that veteran theatergoers had never experienced before.”

Visceral intensity of that kind is almost impossible to deliver on film, with its multiple takes, its editing, its total separation from the mood and character of a particular audience in a specific theater. But Brando did it in Stanley Kramer’s 1950 film “The Men,” in which, playing a wheelchair-bound paraplegic, he picks up a crutch and destroys a glass-enclosed dayroom with an explosive ferocity that left you stunned. Veteran moviegoers had never seen anything like it either. In ten seconds he changed film acting forever.

His best period was short, from 1950 through the film version of ‘Streetcar’ (1951), “Viva Zapata” (’52), “Julius Caesar” and “The Wild One” (’53) and “On the Waterfront” (’54). “The Godfather,” “Apocalypse Now” and “Last Tango in Paris” came much later, of course. But they were exceptions in a career largely filled with grotesque self-indulgence and a self-loathing turned outward—it became de rigueur in most of his films for him to be beaten bloody and comatose, when not shot dead. Long before his death in 2004, he’d blimped out (like that other young genius, Orson Welles) in prophetic display of a figure no one would bank on anymore. Personal tragedy and the ravages of fame—inconceivable now in Selfie America—drove him into reclusiveness.

Early on, Brando was beautiful. He was virile, sexy, irresistibly fascinating, with a smile as big as a Nebraska cornfield and a nearly feminine delicacy that set off his physical power. Like most people, what intrigued me about him was that he was at least as interesting and provocative off-screen as he was on. He wasn’t a Method actor in the Actors Studio sense (he loathed Lee Strasberg as a pint-sized, tyrannical manipulator), but under Stella Adler’s tutelage, which blended the classic tradition of acting as a noble profession with the Stanislavskyan emphasis on the reality of the moment, he was in constant search for what Norman Mailer termed “(catching) the Prince of Truth between disguises.” The search took him to the murky bottom of the human condition. Acting is lying, he said. But he reminded us that we’re acting all the time as we improvise different faces for the world, and self-justifying masks for ourselves.

But what moved me most was the continual surprise he embodied by telling the truth, not just grand portentous lapidary truth, but basic stuff that made sense. Yes, America had a horrible civil rights record. Yes, its treatment of Native Americans bordered the genocidal. Talk shows aren’t really about conversation, are they? And what makes you think you know somebody because of his or her roles? People come up and look at you, he said, like you’re in a zoo.

We like to congratulate ourselves on cheering the outsider, but when a real one shows up, we don’t like it if he doesn’t join in on the game. For a long time, Brando was a fresh breeze that turned out the air of bad faith that still characterizes the entertainment industry as well as the country. He reminded us of things we thought we knew, or should have known, but had forgotten about or ignored. In retrospect, he reminds me of hope. That’s what I miss most about him.

Best summary of Brando’s essence and impact on record. share the wealth !

Agreed! He’s my favorite actor…even though his best work was short before he started making “paycheck” movies.