[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”qq4k2gwK5FqCbEAvppoCYx8tAgWoXajG”]

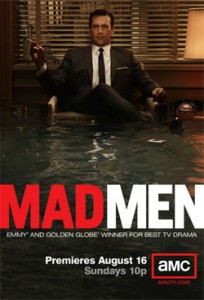

HERE at CultureCrash, we are split on the advertising chronicle Mad Men. Mostly, I think the early seasons were among the best television ever, even if recent seasons have become mere Age of Aquarius soap operas. Our guest columnist Lawrence Christon has no love for the show, early or late. Here is his response to the program’s farewell, and to its read of a complex era of American history.

“Mad Mania: A Postmortem”

By Lawrence Christon

During “Mad Men” season, Monday morning postings on smart websites like Slate, Salon, The New York Times and the more trendy than smart Huffington Post brought such eager, exhaustive commentary and analysis of the show that I was often compelled to check it out lest I miss the latest pile-on in the chatterati’s topical discourse. And each time I did, I’d wonder what the fuss was all about.

This week was no exception, and once the communal play-by-play spilled over into national obsession, the kind of episodic media paroxysm that thrashes around Baby Jessica in the drainpipe or Bruce Jenner’s sex change before pausing to wait for The Next Big Thing, I wondered even more. Was Mark Greif right when, in reviewing the culture’s fixation on “Mad Men” for The London Review of Books, he concluded, “We’re doomed”? On the other hand, some intelligent people have gone all in on this show, and written sensitively and keenly about it.

It really doesn’t matter any more that, from the point of view of dramatic structure, or dramaturgy, “Mad Men” wasn’t very good. It had moments. There were just enough coy signifiers sprinkled through its vacuous expanse to encourage people to read in a profundity that most of the time wasn’t there. Scenes were posed rather than played; the actors were throttled with period attitude and the sense that every moment had been carefully set up to make a point. It was a writers’ and designers’ show rather than an actors’ and director’s show (ideally it should blend these all), but the writing  was soap-opera thin and the design static, so that it had all the scenic dynamism of those bourgeois gents grouped on the Dutch Masters cigar box.

was soap-opera thin and the design static, so that it had all the scenic dynamism of those bourgeois gents grouped on the Dutch Masters cigar box.

At the center was Jon Hamm’s mostly monochromatic performance as Don Draper, a man reinvented but still not satisfied with the result. Hamm is a good-looking guy of the tall, dark and handsome school, and I’ve wondered if his casting wasn’t intended in part to echo an American Sean Connery (whom he resembles); narratively speaking, a corporate Bond with a back story. Like Bond, he bedded women without much liking them. Unlike Bond, he had no glint in his eye. Neither did the show.

The biggest turnoff for me was its insularity from the age it purported to reflect. Robin Williams famously said that anyone who remembers the ‘60s wasn’t there. “Mad Men” tried to remember, but it wasn’t there either. There were tangential inclusions, but there was no way for anyone around at the time to shut out the sound and the fury of the most lurid decade in American history, where the baby boomers, prepared to marshal their idealistic energies behind a glamorous young president, tipped into rage and the grief of abandonment after his assassination.

It was an age of assassination: Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert F. Kennedy. It was an age of violence: riots and protests, black nationalism and Bloody Sunday in Selma, mayhem in Chicago, fire in Detroit and L.A. There were sit-ins, be-ins, die-ins. Weed and LSD supplanted booze and cigarettes. The soundscape radically changed, from Perry Como and Elvis to The Grateful Dead and the lead guitar licks of Jimi Hendrix that cut through the haze over Woodstock nation like the shriek of a jet engine. Generations barricaded themselves against each other. Hard hats snarled at hippies. The color scheme brightened into tie-dye rags as the Boomers regressed into barefoot chant, but at Kent State saw that the reactionary forces of the country had the guns and meant business. By the end, when early accounts of the horrible Manson family murders couldn’t determine the body count, Joan Didion remembered that it almost didn’t matter; no one was surprised.

Through it all seeped the acrid smell of the war in Vietnam, where priapic American technology dropped its fiery load on a rural country populated with a mostly mild people engaged in their own nationalist conflict. The Boomers eventually withdrew into the BMW showroom display of the Me decade, and left the field to the Reaganauts and buccaneer capitalism. America still hasn’t recovered.

There’s been speculation, partly fueled by show-runner Matthew Weiner, that “Mad Men” was about Gen X-ers trying to crack the code of their parents’ guarded hearts. Some have thought it struck a nostalgic fondness for an era of greater Rat Pack freedoms (booze, butts, broads) now considered sexist, unhealthy and uncool. (Toots Shor: “We died younger then, but we had a lot more fun.”) Some have declared it a definitive women-in –the-workplace saga. And then there’s the classic corporate America theme, sounded in the ‘70s musical “A Chorus Line” and mirrored in Hamm’s dour expression: “Who am I anyway? Am I my resume?”

For me, the last episode really did sum up “Mad Men’s” popular run: Don Draper ohm-ing in an ashram, finding inner peace and the blissful energy to go back into the world and make a nutritionally useless bottle of soda a product-placed symbol of universal love and harmony in voices raised on high. (Am I the only one who thought it dubious for a fictional character to imply credit for a real cultural phenomenon?)

In short, a successful return to genteel hustling.

That ending defines “Mad Men’s” exaggerated importance: The first principle of the hustle is that you can’t be had unless you first enjoy it. Judging by the response, a great many have.

I really enjoyed because there is very subject interençante and educational at the same time.