[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”jmgPWNAcri7qqzMjI9cU8cSfZfom5qHL”]

INTERESTED in songs about love and sex going back to ancient fertility rites, through the medieval troubadours and the German art song and into the age of “Tangled Up in Blue,” Ziggy Stardust, and bedroom R&B? Then you may want to get your hands on Ted Gioia’s new secret history, Love Songs, just out on Oxford University Press.

Ted is an old friend; two decades ago, before I knew him, I read his essay collection The Imperfect Art and his essential West Coast Jazz. (He’s a fellow disciple of Arnold Hauser, the Hungarian small-m marxist author of the four volume The Social History of Art, from the caves to the age of film; it is a very small club.)

What follows is our conversation.

++ Over the years you’ve written about West Coast jazz, the Delta blues, the American Songbook, work songs and healings songs. What made you want to write a history of love songs going back to Sappho and beyond?

I’ve always found myself drawn to the side of music that is usually ignored by music historians—namely what is happening to the audience. How is music changing their lives? What role does music play in our intimate, personal life, where it is hidden from view? Or in our communities and institutions, where it is always scrutinized, and often censored and prohibited?

I’ve always found myself drawn to the side of music that is usually ignored by music historians—namely what is happening to the audience. How is music changing their lives? What role does music play in our intimate, personal life, where it is hidden from view? Or in our communities and institutions, where it is always scrutinized, and often censored and prohibited?

This side of the story is almost always neglected in books on music. They focus on the stars and celebrities, and rarely even notice the ways music transforms and enchants our day-to-day lives. But this part of the story desperately needs to be told. The traditional view of music history is lopsided. What I’ve found is that the evolution of music looks very different—indeed, radically different—when viewed from perspective of gritty, everyday life.

So I have become almost obsessed with the idea of turning music history on its head. Over the last two decades, I have conducted research on the real history of music, the tale of how it actually works in the context of human society. Ten years ago, I published the first two books of a trilogy—Work Songs and Healing Songs. But I saved the biggest subject for last, namely a 5,000 year chronicle of how song impacts courtship, romance and sexuality. I’ve now told this story in my book Love Songs: The Hidden History.

++ Darwin and others (Freud?) thought the urge to music – and perhaps the entire art instinct – was sexual in origin: the “peacock’s tail” argument. So is it fair to say that all songs are essentially love songs?

I was originally suspicious of Darwin’s view that music was driven by sexual selection. He focused so much on bird songs, and I was skeptical about its applicability to human music and institutions. In an early draft of my Love Songs book, written back in 2003, I emphasized all the flaws and limitations of his theory.

But I’ve changed my mind during the last decade, largely on the basis of little-known research in various medical disciplines and the social sciences. In the final draft of the book, I admit begrudging respect for Darwin’s theory. I’ve found that it explains a number of peculiar aspects of music history that are otherwise inexplicable. I still am hesitant about attempts to reduce music to biology—artistic works are too multivalent for scientists to ever deal with all their subtleties. But I am convinced that certain biological imperatives explain the persistence of various themes in the love song over thousands of years.

++ Opposition to love songs has come from all quarters – from the medieval Catholic church to British punk rockers. Is this a constant throughout human history? Is it mostly a fear of sexuality? Why so divisive?

For many years, I puzzled over what I was finding in my research into love songs. I had always viewed this music as soft and sentimental, but the history of these songs was filled with repression and violence. I only gradually realized that the love song had served as a major force during the course of history in expanding personal autonomy, individual freedom and human rights.

In retrospect, this now makes perfect sense. Whenever a new kind of love song emerges, it usually represents an attempt by the younger generation to take control over their personal lives. They want more freedom to love, to live, as they choose. The older people, and the patriarchal institutions, are scared by these songs, and conflict invariably ensues.

Eventually new love songs become mainstream, and the conflicts are mostly forgotten. We’ve seen that in recent years with rock ‘n’ roll, which once was too scary to put on TV, but now gets celebrated at the White House and other bastions of respectability. In my book, I show that this same process has happened repeatedly throughout history. New ways of singing about love emerge, create social upheaval, and then, at the last stage, get accepted as part of everyday life. Usually the conflicts are left out of the music history books.

For this reason, I have to laugh when people act smug and dismissive about love songs. They think it is wimpy music for sentimental fools. In fact, the love song has always been the most radical and dangerous kind of music. But until you learn the hidden history, you could easily miss this fact.

++ You’ve found something startling in your research on the origins of Western love song coming from the medieval Muslim world, and not the French troubadours, as we’ve typically thought. Can you tell us a little about it?

This was perhaps the most surprising discovery I made during my research. Most history books give credit to the troubadours, who flourished in the court life of southern France during the late medieval period, as creators of the modern Western love song. Their extravagant notions of courtship and service to the beloved still haunt our romantic notions today.

Yet I show in my book that most of the key elements of the troubadour’s approach to the love song came out of the Muslim world. Back in the ninth century, the female slave singers of the Middle East were already singing about being in servitude to the beloved—and for a very good reason. They were actually slaves, and were forced into this servitude. These singers came to Spain during the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula—right up to the border of Provence, where the troubadour lyric began. From these female innovators, the nobles of southern France learned to sing their similar songs of servitude. But now we are confronted with something very strange, members of the nobility are play-acting the part of the slave to love.

In some ways, this anticipates the bizarre spectacle of the minstrel shows of 19th century America, in which the ruling class gets renown for imitating the musical styles of forgotten slaves. The same thing happened in medieval culture, but the history books have only told half the story—the part about the slaves gets eradicated from books on the troubadours.

++ Besides the Moorish stuff, what surprised you the most in writing and researching Love Songs?

Before writing my book, I never realized how important women were to the evolution of the love song. I found, again and again, famous men getting credit for the lyrical love expressions of women. This was true with Confucius and the Shijing, Solomon and the Song of Songs, Pindar and the Greek lyric, and at many other junctures in history. In each of these instances, the famous man draws on the breakthroughs of the female innovator.

++ My guess is that after thousands of years of love songs, especially after “The Summer of Love,” there was a sense that the love song was exhausted, trivial, commodified… Was that fair? Was anyone, or any movement, able to push love the song forward in a fresh way, or had it become speech in a dead language?

Every generation tries to rewrite the language of the love song in some shocking new way. In the 1920s, you could hear this in the transgressive blues songs. In the 1950s, rock ‘n’ roll led the way. Later on punk rockers and hip-hoppers also aimed to shock us with their bold love songs. And, in a different way, Miley Cyrus and Lady Gaga are doing the same in the current day. Yet some aspects of the music never change. In my book, I show how Miley Cyrus represents, in some degree, a return to the fertility rites of ancient Mesopotamia.

++ Most love songs celebrate the body and soul of the beloved. But perhaps my favorite lineage may be the breakup songs, the sour grapes song, the kiss-off song. Dylan wrote a million of these (“Positively 4th Street”), and the Smiths, Lloyd Cole (“2 cv”), Leonard Cohen, Richard Thompson (“I Misunderstood”), and a few others took it to a very high level. Are there historical roots for this, such as the Roman song of the “excluded lover”?

In the earliest days, all love songs had to have a happy ending. Why? Because they were connected to fertility rituals, failure was not an option. You needed an exemplary coupling for the crops to crow and the kingdom to remain stable. But starting with the Egyptians, and continuing with the Greeks and Romans, the unhappy love lyric emerges as a major force in human song. The Romans provide a fascinating case study. They both recognized the importance of unhappy love, but also were deeply uneasy about it. The lover excluded at the door of the beloved was frequently angry or drunk, and the Romans often preferred to ridicule, rather than admire, these passionate fools.

Frankly, I believe that we inherited our modern-day shame and embarrassment over love songs from the Romans. Even today, people are embarrassed to admit that they listen to sentimental love songs. Most of our songs are about love, but music writers are generally reluctant to write directly about the most romantic songs—in fact, they almost always prefer to express their disdain for this music. As I show in my book, we got this attitude from the Romans. Like them, we are compelled to sing about love, but uneasy about admitting it.

++ Do you have a favorite long song or two?

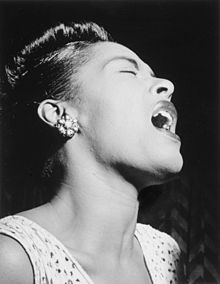

When it comes to love songs, I am definitely old school. I will turn to Billie Holiday performing with Lester Young on “I Can’t Get Started,” or Ella Fitzgerald doing one of her songbook numbers, or Nat King Cole singing “Nature Boy.” I never tire of hearing Johnny Hartman singing with John Coltrane. But I also like a number of singers still with us in the current day, whether old-timers like Tony Bennett and Mark Murphy, or not-quite-so-old stars such as Cécile McLorin Salvant, Kurt Elling and Gregory Porter. And I should mention some talented singers who deserve to be much better known, such as Susana Raya, Sara Gazarek and Joanna Wallfisch. Wallfisch has a new album coming out in a few days called The Origin of Adjustable Things that I have been enjoying a lot.

++ My hunch is that part of the skepticism about/ resistance to the traditional celebratory love song is the sense that it is too easy — almost like painting a picture of a sunset or taking a photograph of a waterfall. That it’s been done, and that to write about love is sort of cheating, that it’s tennis without the next, since every digs love and the pleasures of the flesh.

You see this, I think, as early as Billy Strayhorn and Cole Porter — the sense that the form needs to be inverted or ironized or something. (The fact that both these men were gay may tell us something, but I’m not sure what.) And we see a similar spirit, inflected differently, in people like Elvis Costello or Gang of Four, both influenced by punk, which was committed to political lyrics and social criticism. Feminists like Joni Mitchell and Liz Phair had their own take on this which may have some things in common.

So do you pick up the same strains as I do? And was it fair? Is it easy — has it ever been easy — to write a great love song?

I studied thousands of love songs while writing this book, and it is scary to see how many cliches and tired metaphors get recycled in this music. Most love songs simply string together empty phrases that are borrowed from earlier love songs. Yet every one of these hackneyed phrases started out as something fresh and new. It’s only after decades of repetition and imitation that they start to sound lazy and formulaic. Petrarch invented a new way of writing love lyrics in the 14th century, but 200 years later song writers were still imitating his attitudes. By that time they had become cold and hollow. But you can’t blame Petrarch — he was a visionary. John Gay created a musical revolution with The Beggar’s Opera, but over the next half-century more than one hundred imitation operas were staged, and his earthy way of dealing with love songs was now just one more tired formula. But you can’t blame John Gay — he was an innovator.

This is the endless cycle of the love song. Just when we think that the love song has reached a dead end, something new comes to bring it back to live. In the late 19th century, the cabarets of Germany and France reinvigorated the love song with spicy new ways of singing about romance. In the 1920s, the blues did the same thing in America. And then we arrive at the golden age of American songwriting in the 1930s, when Gershwin, Porter, Berlin and others reinvent the love song one more time. As did the Beatles and the Stones in the 1960s, and then the singer-songwriters of the 1970s, and the rappers of the 1980s. Every revolution finally comes to an end, but there is always a new one around the corner. So even if the love songs of the current day are starting to sound a little threadbare, I am optimistic about the future. At some point, a new visionary will arrive to teach us to sing about love in a fresh, new way.

My life is also changed by love song, these type of songs are the backbone of human being I think so.