[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”jzqLTuB5rmQYkgMOc3cPogWpL4eHcyGM”]

For the last two weeks I’ve been touring behind my book, doing lots of public-radio interview, and in some cases dueling with people who disagree with me. The concentrated attention has made me think long and hard about my stance and my values.

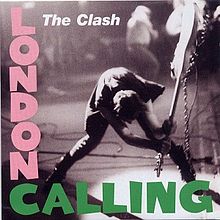

One of the things I’ve realized is that my politics are an odd cross between Teddy Roosevelt and The Clash. (To be clear, I don’t agree with either the Republican president or the British punks about everything.) The latter is not really a surprise to me; I was crazy about punk rock in high school and college, London Calling may be my favorite album post-Beatles, and one of its songs, “Lost in the Supermarket,” lends its title to my chapter on runaway capitalism and unchecked consumerism.

Here is that great song, with a montage of Clash posters and album jackets.

The Sex Pistols represented a different lineage based on consumerism, nihilism, and Warholism. (I loved them at the time but they now remind me of Jeff Koons’s faux-rebellion.)

What set the Clash apart for me was telling the truth, telling it with force (and artistry — their songs post-debut were beautifully crafted), and not letting the bastards win. These are lessons that shaped my point of view profoundly.

It is deeply ironic that you so strongly and justifiably attack the negative effects of unmitigated market forces on culture, while embracing forms of music indelibly intertwined with the music industry, a social force that is one of the clearest examples of “bastards” and their “runaway capitalism.”

And by this, I don’t not mean to embrace classical music elitism or any such thing, which under our funding system is yet another form of cultural plutocracy. It seems people are so buried in our market controlled society they embrace it even as they resist it. The acculturation of the market is so deep they can’t even imagine any other world.

We had a hedge back home in the suburbs

Over which I never could see

It’s a very pervasive problem. Any thoughts about this are much welcomed.

Culture — and capitalism — are full of tensions. But I see no contradiction between being on the political left and a fan of the Clash, Beatles, Miles Davis and Leila Jo. Is the music industry perfect? Of course not.

If there is a better model for culture than the mixed economy — neither all state control on one hand, nor pure consumerism on the other — I don’t know what it is. My problem is that the mix has gotten unbalanced lately.

Thanks. This would be predicated on the assumption that Clash is in the same category as the other three you mention. These subjective evaluations make it difficult to positions arguments about cultural collapse and possible solutions. How do we evaluate lowered cultural standards when those very standards have become the language we speak?

I think of the 3 minute radio format that allows for commercial breaks, the short form as a tool of marketing sensory bombardment as opposed to the longer spans of deeper thought; the lack of musical dimension in the clunk, thunk, clunk, thunk kick pedal bass drum; the simplistic harmonies; words that can’t be understood unless one looks them up, and then only to find that they are fairly superficial and with a doggerel character.

This, of course, will be conveniently labelled snobbery and elitism, but is that a sufficient argument? Tom Frank’s “One Market Under God” (which I learned about on your blog) eloquently addresses the problems with postmodernism’s leveling of the arts and how it served the mass media. It’s not so much a matter of political positions or economic systems, but rather the highly complex problems presented by correlating aesthetic concepts with ideas about what creates a healthy society.

I have your book on order, so perhaps it will answer some of these interesting questions.

” think of the 3 minute radio format that allows for commercial breaks, the short form as a tool of marketing sensory bombardment as opposed to the longer spans of deeper thought; the lack of musical dimension in the clunk, thunk, clunk, thunk kick pedal bass drum; the simplistic harmonies; words that can’t be understood unless one looks them up, and then only to find that they are fairly superficial and with a doggerel character.”

This is not snobbery or elitism. It is ignorance.

The usual response to challenges of academic orthodoxy.

It’s morning here in Europe, so I have a little more time to add some more thoughts. One of the biggest problems artists face is avoiding the monolithic orthodoxies that often define their fields. These totalizing ideologies are also a cause of culture crash. This problem is now widely acknowledged regarding the serialists and related forms of music that dominated contemporary classical music for about 30 years from the 50s through the 70s. In the USA, this type of music collapsed precipitously as postmodern concepts began to enter the field, but by the mid 90s postmodernism had become a similar totalizing academic orthodoxy.

This was deeply ironic because the purpose of postmodern thought was exactly to decenter these forms of orthodoxy. In classical music, the high priests of postmodernism have become the very Pharisees that postmodernism was intended to dethrone. The two fields that are most severely affected by postmodernism as a quasi-totalizing orthodoxy are musicology and composition. Performers are less influenced because their standards have a much more objective basis and are thus less susceptible to totalizing ideologies.

I embrace postmodern thought but reject its totalizing orthodoxies, as I discuss in this commentary from 2007:

http://www.osborne-conant.org/email2/pomo-weakening.htm

Another irony is that contemporary classical music in Western continental Europe, especially in Germany, France, Italy, and Holland, largely rejected American postmodernism and continues to maintain a very orthodox modernism. It is firmly based in their systems of public arts funding and almost has the character of an official Staatskultur. It is a crushing monolith just as Postmodernism has become in contemporary classical music the USA. Artists become caught in the jaws of these two monoliths which tolerate little dissent.

As with most totalizing ideologies, its practitioners are largely incapable of dialog. They can only preach to their choirs. They colonize, or attempt to colonize, the institutions they enter. Outside voices are quickly reduced to straw man arguments. They are pilloried as elitist, snobs, ignorant, etc., but very little is done to substantiate their dismissive views. Those who want to more deeply examine postmodernism — or expand its views — are apostates whose perspectives are beneath discussion. It has thus become difficult for postmodernism in American classical music to address the lack of growth in its thought. The result has become intellectual and artistic stagnation.

Postmodernism in the USA thus has difficulty addressing the appropriation of its philosophy by neoliberal economics. In classical music, it has difficulty acknowledging that an 80 year-old tradition of American pop music will not have the same substantial body of literature as the 800 year-old classical tradition. It is reluctant to address the issues created when relativism becomes excessive, and especially the affects this has on critical analysis. And they are reluctant to discuss that the pop music they esteem is mostly limited to the English-language music industry, and that there is an inherent ethnocentricity and hegemony in their views.

The philosophy even becomes stressed when comparisons are made between the extreme variations in quality in popular music itself, because it creates a specter of critical analysis that threatens their orthodoxies. To deny that Clash is in the same category as the Beatles or Miles Davis thus becomes the apostasy of an ignorant, snobbish, elitist. No more discussion is required, the heretic is to be burned at the stake.

To illustrate some of these points we might compare Madonna and Lady Gaga. Early in her career Madonna literally had problems matching a pitch with her voice. Hard disk recording was still not very developed in the early 80s, and auto tuning programs had not yet evolved. Even putting tons of reverb on her voice and sampling segments of her vocal tracks to create special effects didn’t hide the truth about her lack of musicianship. (To note all of this, of course, is just the “ignorance” of an apostate.)

Complex systems of rationalization began to evolve. Madonna embraced and popularized feminist ideals which was important work. This became a rationalization for overlooking the limitations of her musical abilities. The poor quality was also glossed over by the excellent videos created for some of her songs.

Later, when Madonna took the role of Evita in the 1996 film of the same name, she received a lot of music lessons and vocal coaching which improved her skills somewhat, but her standards were still low.

Lady Gaga, by contrast, has some fairly decent musical skills. They are on display in this video, which reaches a level of musicianship well beyond anything Madonna ever achieved:

http://www.vevo.com/watch/tony-bennett/The-Lady-is-a-Tramp/USSM21101750

So let’s forget this idea that everyone who criticizes postmodernism’s excesses are just ignorant elitists. Let us acknowledge that postmodernism in America has assumed a rather hegemonistic character. And above all, at least in this blog, let’s be honest about the appropriation of postmodernism by neoliberalism and the serious problems this causes.

Of course apostasy I present here will be beneath a response, but I hope some readers might understand what I’m saying.

“In classical music, the high priests of postmodernism have become the very Pharisees that postmodernism was intended to dethrone.”

I’d be interested to know who these priests/Pharisees are.

Tom Frank devotes a chapter of his book “One Market Under God” to this problem. He mentions many of them by name and discusses their work. There are several bibliographic references in the end notes. I actually like a lot of what these scholars do, especially Donna Haraway and Susan McClary. The problem comes when the thought turns into a mass movement and becomes an academic orthodoxy. I outline here some of the problems this has caused for classcial music:

http://www.osborne-conant.org/email2/pomo-weakening.htm

Tom Frank’s work is absolutely essential; he was a major shaper of my book, one of my four guiding spirits

I’d love to see Dr. Fink pursue his point here!

Certainly you can extend the Tom Frank argument, as at least one scholar has done, to suggest that all music is advertising. But to me, Son House, Dinah Washington, Schubert’s quartets, Pavement’s albums, Monk’s music, and much of the work of the Clash is a sign that there is something divine in human beings.

Re an earlier point of Mr. Osborne’s: I too consider “longform” in writing and everything else, and an extended attention span, crucial to culture (as well as democracy.) But again, I don’t think it’s impossible to love Beethoven’s symphonies and Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain and Bergman’s films alongside London Calling and Big Star and the singles of Stax/Volt. I simply don’t see the contradiction.

When it comes to loving these arts works, I don’t see a contradiction either. Life would not be the same without works like Lennon’s “Imagine.” And isn’t love of art and what it says about humans what it is really about?

Indeed!

(Though I’ve heard Imagine too many times)