[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”AkwrwxM6eGKNL3GVzj0NAKOSml0rfK6D”]

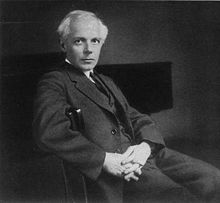

YOUR humble blogger came out of a performance of Duke Bluebeard’s Castle yesterday reminded of what a bloody genius Bela Bartok was — and I mean that just about literally. The production at Los Angeles Opera is brutally sharp, filled with sexual menace. The swelling, at times astringent music itself offered a dark kind of beauty to accompany the pain.

What may be most impressive about the performance is that the same stage director — Barrie Kosky, who runs an opera co in Berlin — also offered up a pastel-toned, often-comic reading of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. From the sweet colors and lavish gowns of the Purcell to the stark, pitch-black look of the Bartok, here is a director with a contemporary sense of visual style. Overall, it made for a much hipper double-bill than the usual Cav-Pag.

The Bartok hit me harder than the Purcell, but the Irish mezzo-soprano who played Dido, Paula Murrihy, has one of the clearest and most beautiful voices I’ve heard in years.

Here’s how Mark Swed begins his review:

Four cautious years after staging Achim Freyer’s cutting-edge but coffer-draining “Ring” cycle, Los Angeles Opera has once more sharpened its edge, and dangerously so. On Saturday night, it mounted a peculiar double bill of Purcell’s delicate “Dido and Aeneas” and Bartók’s indelicate “Bluebeard’s Castle.”

Purcell’s exquisite British Baroque miniature is as gorgeous to behold as anything the company has mounted on the Dorothy Chandler stage. It is lovingly performed. That the humor can be wicked and transgressive only makes the tragedy all the more touching in the end.

Bartók’s expressionist early 20th century drama is the unsettlingly awful opposite. There is nothing nice to look at, just a couple’s pain made plain. The performance is violent. What is here transgressive is that horror also makes a mass murderer somewhat touching in the end as well.

I’ve loved Bartok since I first heard his music, and have a special passion for his string quartets. But I can’t wait to hear Bluebeard again. (For what it’s worth, my wife, who’s been seeing opera for longer than I have, loved them both but preferred Dido.) In any case, see them before they go. Kudos to LA Opera for putting on something this adventurous.

UPDATE: As I think back to Bartok in particular, and the way he’s able to capture such a wide emotional range, using dissonance within an essentially tonal structure, and bring a modern sensibility to music that is still essentially tuneful and accessible: What if Bartok, and not Schoenberg and his serial disciples, had set the terms for 20th century music? How would classical music have sounded different over the decades, and what would its audience be like today?

I welcome reader thoughts on this.

As a baseball fan, I am overly prone to giving “best of …” labels (as in “best opposite field hitter”). So I will plunge in and say that I think of Bartok as the most important 20th century composer.

He was, without a doubt, as important to ethnomusicology as Marx was to economics. That alone should elevate him.

But he wrote such a dense and diverse body of work, you can sample here and there among orchestral or opera or chamber or piano and find masterworks. His music stands alone, then throw in academic and cultural impact, and he’s a composer without peer in that century.

No argument w Mr. Moore — I might go for Shostakovich some days, but Bartok was a titan

No f in Barrie Kosky’s name.

Thanks — fixed.

Regarding Schoenberg … He was a nasty bump in the road (and concert audiences haven’t recovered, still believing new music is inherently off-putting and, to standard-issue human ears, unmusical.

But the world has caught up with Bartok, thanks to the globalization of media’s reach. World music, as we call it, is now the most vital new blood invigorating most musical genres, and Bartok led the way.

The more I hear of world music (I am absolutely delighted by DakhaBrakha, the Ukrainian ‘ethno-chaos’ quartet) the more I appreciate and enjoy Bartok. It was Bartok who pointed the way to break out of the Austro-Germanic tonal stranglehold, not the dreaded Serialist.

I agree with Milton here with the hedge that the term “world music” usually refers to music outside the US-European axis. By some definitions, it includes various folk forms, including Celtic music, but it mostly means African, Middle Eastern, South American, pre-modern Asian music, etc.

So not sure how Bartok — who I also adore — fits in. He drew from folk forms but was a classically trained dude who fit the folkloric to a modernist pov — very different from most of what’s typically considered World Music.

Schoenberg contributed much more to 20th century than just serial composition:

-He was a classical theorist, composition teacher (one of his students was John Cage), and painter. He never taught serial methods to his students, considering them inconsequential to a piece’s quality.

-His work inspired La Monte Young (the first minimalist composer), who claimed to hear proto-minimalism in Schoenberg’s and Webern’s music.

-His work, specifically the 1909 opera “Erwartung”, also influenced Bartok’s “Bluebeard’s Castle”. Both Bartok’s and Stravinsky’s later music uses serial practices.

It seems like the 20th century rift between the living composer and the audience’s taste has more to do with bad composers justifying their lousy pieces by saying they used the same method that Schoenberg did (which is like saying a piece of music is good because it has major and minor chords, just like Mozart’s does). Also, theorists have obsessed over the serial methods of the second Viennese school because they are so easily quantifiable, while disregarding the timbral, rhythmic, melodic, and emotional beauty of that music

I also love Bartok but the what I find most important about 20th century music history is that it proves that there is room for many different types of artistic philosophies, each equally valid if rendered clearly and sincerely. The modernist Austro-German aesthetic is no longer the dominant musical force, but it can’t be proved wrong by the popularity of a different aesthetic, either.