[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”BuXkCBK03a5HewprMNjDnGKXPBsl6eH9″]

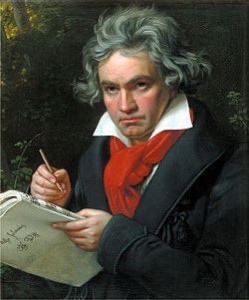

A FASCINATING Alex Ross story in the New Yorker looks at the incredible impact of Beethoven — has any artist reshaped his art form more? — and then acts if he has kept music from evolving. Here’s Ross on Ludwig van:

He not only left his mark on all subsequent composers but also molded entire institutions. The professional orchestra arose, in large measure, as a vehicle for the incessant performance of Beethoven’s symphonies. The art of conducting emerged in his wake. The modern piano bears the imprint of his demand for a more resonant and flexible instrument. Recording technology evolved with Beethoven in mind: the first commercial 33⅓ r.p.m. LP, in 1931, contained the Fifth Symphony, and the duration of first-generation compact disks was fixed at seventy-five minutes so that the Ninth Symphony could unfurl without interruption. After Beethoven, the concert hall came to be seen not as a venue for diverse, meandering entertainments but as an austere memorial to artistic majesty.

Ross, of course, has written how dangerous classical music’s shift to becoming an austere memorial has been; it’s one of the main themes of his excellent book The Rest is Noise. By making culture into a religion, Beethoven’s music (and classical music itself) set up expectations it could not fulfill, and guaranteed a stuffiness and sense of exclusion.

In the New Yorker piece he writes about the beginning of classical music as a backwards looking art form — it wasn’t always that way, folks! “In the course of the nineteenth century, dead composers began to crowd out the living on concert pr ograms, and a canon of masterpieces materialized, with Beethoven front and center.” It amounted, he writes, to “the shift on the concert stage from a living culture to a necrophiliac one.”

ograms, and a canon of masterpieces materialized, with Beethoven front and center.” It amounted, he writes, to “the shift on the concert stage from a living culture to a necrophiliac one.”

Of course, various art forms have had dominant figures who inhibited those who followed. Southern writers in the period after Faulkner have complained about the anxiety of influence, for instance. But the case of Beethoven has some specific difficulties for those who follow.

Part of it comes from a new notion of the genius — self-made, rather than by God — and the whole machinery of heroic/individualistic Romanticism.

Politics also assisted in Beethoven’s elevation. The disorder of the Napoleonic Wars, which redrew the map of Europe and ended the Holy Roman Empire, caused many to look toward music as a refuge. Amid universal chaos, Beethoven exuded supreme authority.

Much of Ross’s story is about the recent Beethoven bio by Jan Swafford (one of the most lucid writers on classical music) and some other books on the composer, including a novel. In any case, I commend the Ross essay to all of my readers.

Ross’s thoughts about Beethoven are interesting. One might also extend the ideas to arts journalism which is in many respects anachronistic. Most of the journalistic practices in the arts used today appeared in the 19th century and were closely associated with the rise of the bourgeoisie and cultural nationalism. The principle effect of most arts journalism was to celebrate the artist-hero as a symbol of the nation-state’s creative virility – of which Beethoven was a paradigm. The prototype of this type of journalist in classical music was Robert Schumann. His circle centered around the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik also elevated Bach and Mozart in a similar vein of patriarchal, cultural nationalism.

After WWII, this sort of nationalism and its representative artist-heroes went into a gradual remission and were replaced by the aesthetics of global capitalism. We thus saw a corresponding decrease in the status of arts journalists, since their function as spokesmen for the nation-state’s creative virility became irrelevant.

Global capitalism requires a new kind of feullitonist, a generalist gadfly who is part of a marketing apparatus focusing largely on international celebrity like jet-set conductors, pop stars, famous movie actors, and best-selling authors. Roll over Beethoven. Since original thought and social commentary seldom fit with the corporate media’s financial interests, publications like the NYT and much of The New Yorker are already a kind of People Magazine for moderately educated yuppies. We generally see cultural gossip with a touch of niveau couched in these publications’ self-consciously affected, studiously apolitical urbanity.

This explains the success of chatty and congenial classical music journalists like Alex Ross, Anne Midgette, Anthony Tommasini, and Mark Swed. The arts are to be made socially and politically innocuous. It’s a notably different world from earlier journalists who did not shy away from controversial political views and who were in reality public intellectuals like Edmund Wilson, Paul Goodman, Harold Rosenberg, Lionel Trilling, Mary McCarthy, and Susan Sontag.

These writers shared a desire to exhibit intellectual range, and they were not afraid to challenge the status quo. They found a way to pay attention to specific intellectual topics and yet comment on the larger cultural context in which those topics appeared (a little like this blog, though it is tame by their standards.) This is something sadly missing in most of today’s arts journalism. After the ravages of McCarthyism, the corporatization of the media, and the rise of neo-liberal economic policies, wider social perspectives in the arts became too suspect and the field as a whole became self-censoring and narrowed.

If arts journalists want to maintain their true worth in our post-Beethovean world, they need to exhibit a wider range of knowledge, and be more prepared to present controversial political, social and aesthetic perspectives. Or is all that stuff just noise….? If they remain the bunch of relative one-dimensional wusses they are today, they will be happily forgotten…along with Beethoven, of course.

BTW, the main reason Beethoven became a “bad influence” is because he no longer makes money.

William Osborne’s observations are brilliantly astute with two exceptions. I understand that Beethoven is about the only composer who can still fill auditoriums. He still makes money, and that may be why classical music hangs on in so many cities in America. Classical is not America’s music; blues, jazz, rock, and pop are. The amount of knowledge music critics need is not so much quantitative, but a critic these days must have a deep understanding not only of the philosophical and theoretical traditions of classical music, but also of all the other American vernacular genres that, until around ten years ago, themselves made money. The main thing is that Beethoven wrote for the muse (for God or AS God) and failed when he wrote for the money. Now, in this hyper-materialist age, money IS God, and no one dare get on the wrong side of that equation.

Smart comments, and I am a longtime admirer of Edmund Wilson, Jane Jacobs, and others — that public intellectual tradition is very important to me. But I think I think that what someone like Swed does is very different and much more focused. None of the people you mention would get a job as a newspaper or magazine’s classical music critic these days. That niche has largely disappeared for all kinds of reasons — academia is one culprit, as The Last Intellectuals argues, as is the fading place of the arts in the US — but it is certainly not the fault of Swed, Ross, and the rest.

The problem is that these questions quickly move toward professional relationships that make discussion difficult. History might not be these journalists fault, but far from going down with at least a fight, I see them being very well-behaved, never crossing lines, and essentially collaborating. Who are some mainstream classical music journalists who are transgressive? Or at least some examples from other areas of the arts that might serve as a model? What is arts journalism without the freedom to transgress?

Sometimes the examples of an odd sense of self-imposed collaboration are quite extreme. Here is a case I observed first hand and thus deconstructed fairly closely. Before thinking me biased because of my connections to the case, remember this is only one example of much larger patterns in the field:

http://www.osborne-conant.org/wnyc.htm

“Who are some mainstream classical music journalists who are transgressive?”

William, you say that as if being transgressive were self-evidently a good thing. I don’t agree with that.

Honest, sincere, understandable, well-informed and fair – that’s what I believe classical music journalists should be. If, in a particular instance, that involves being “transgressive” (whatever that would mean), so be it. But the transgressiveness should be a by-product, not a goal.

I’m not suggesting that transgression (for lack of a better term) is an end in itself, but that the spectrum of accepted thought in our cultural discussions is too narrow. This goes far beyond journalism. I think of post-war France and thinkers like Camus, Sartre, Foucault, Derrida, and Baudrillard, all of whom had so much profound influence. They lived in a country that allowed for a much wider range of political and social thought in both journalism and academia. I think this might be why their thinking was much more wide-ranging, and why they seemed to ask deeper questions.

Our public intellectuals generally gravitate toward more narrow topics (e.g. Chomsky and foreign policy, Cornell West and race, Galbraith and economics) and generally do not address the broader nature of Western culture’s core identities. I mention it, because if one is to explore the nature of “culture crash” a broader and deeper approach seems important.

At the same time, I acknowledge that music journalists have to be fairly constrained in their general topic, but I’d still like to see them spread their wings now and then, and definitely stop being so well-behaved. The word goodie-two-shoes comes to mind when I read them. Music and culture is difficult to fully understand and appreciate without placing it in larger social contexts that would stand far outside accepted thought in the USA.

As just one example, name even one mainstream American arts journalist who has written comprehensively about Europe’s system of public arts funding and how it reflects on the private system used in the USA. Deafening silence. Goodie-two-shoes.

To compress a complex argument into a brief time and space — Camus asked big important questions, but he was a novelist and social critic. The post-structuralists, who I adored in college, have in some ways been destructive to the larger discourse. I get into this in my book,

Every arts critic I know — just about — prefers European-style funding.

And call it careerism or whatever — a music critic who wants to stay employed has to write more narrowly about music than say, Camus wrote about society. And let’s not forget — just a few weeks ago, Ross wrote a long, eloquent piece on Adorno and Benjamin and the issues they explored. I’m very glad he and The New Yorker are around.

“Every arts critic I know — just about — prefers European-style funding.” And yet not one has written an article showing the advantages. Why?

No stories about European arts funding? It’s hard to prove a negative, but what makes you say there have been no stories about that? Given the huge range of publications, online and in print, about music and culture, I find that a bizarre accusation. I mean, I’d like to see more of that kind of story, but to say there have been none…?

Not long ago Mark Swed wrote a piece about the need for the US to appoint a minister of culture on the European model. That took guts because it was denounced by some readers and I expect plenty of editors at the paper who think of themselves as market-minded pragmatists jeered the suggestion.

Yes, I remember that we discussed Swed’s Czar article here on CC. As for articles about the European system, I mentioned mainstream journalists to make a search easier, and because I feel it should be a mainstream topic. In fact, I see no articles at all on google, even for small journals. If there is anything significant, it should show up. I too find the absence odd. I wrote an large article in 2004 comparing the European and American funding systems which was published on ArtsJournal, but we need a comprehensive article (or series) in a big publication. My article had about 5000 reads and it gets about 300 visits a month on my website. I really need to update it. It’s here:

http://www.osborne-conant.org/arts_funding.htm

BTW, I wonder if academic and journalistic careerism might be closely related in terms of their causes and effects, and if the two forms of careerism might also feed off each other. These forces for conformity seem to be big factors in causing culture to crash, as it were.

Mind, let’s be careful not to distort what Alex is and isn’t saying in that essay.

Though he didn’t make the distinction explicit with the words I’m about to use, I thought it was very clear in what he wrote.

Alex isn’t arguing that Beethoven’s music and its influence kept the entire field of classical music from evolving. The author of The Rest Is Noise is well aware of all the ways the composition of classical music has evolved since Beethoven’s day.

Alex is arguing that Beethoven’s music and its influence have kept mainstream concert hall culture from evolving in a healthy way – turning it, for better or worse, into a museum culture.

This is a good point

To go back to Ross’s article: one thing he doesn’t mention is how the structure of the musical world changed after the French Revolution. Until then, composers were mostly employed by princes and the Church to compose works specifically for them, their courts, their institutions. Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven of course did all begin to break the mould and worked to change the status of the musician to that of a freelancer who supported himself with concerts and individual publications. But with the disappearance of the aristocrats as commissioners of new art, the big backlog of existing concert art became more important (more reliable and cheaper to perform) for a broad nonaristocratic audience. From there it was a short step to forming a fixed canon, with Beethoven in the lead.

Swafford does an excellent job in the bio of detailing the influence of French Revolution anthems and songs on Beethoven.. The final movement of the Ninth, Swafford says, could have been sung in the square in France during the fervor.

Also, Ross doesn’t make much of this (nor does Swafford) but it’s so ironic that Beethoven was intensely jealous that Haydn’s anthem was adopted as the national anthem of Austria. Now, Ode to Joy in the anthem of all of Europe.

Ross over-fixates on Beethoven, ignoring other important composers of that era. Beethoven was indeed ahead of the time in some respects, but also very much a product of his times. So, if Beethoven could be called a “bad” influence, then you would have to include his inner and outer circle. And the term “bad” seems rather puerile and unsophisticated, don’t you think?