[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”cA06WrBWrX1QdeSrOH4sa9wEJQ8lEH07″]

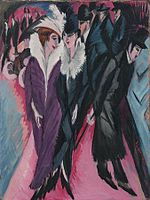

READERS of this blog know that one of my primary concerns is the way economic shifts — especially as they affect rents and the costs of living — have direct and profound meaning for the creative class. So I want to go back to The New Republic story on Berlin and other “cool” cities

But the greatest risks posed to the “next Berlin” are likely to stem from an international real estate market that has grown dramatically since the 1990s. As James Surowiecki detailed in a recent New Yorker, liberalized purchasing rules have allowed “a torrent of capital from wealthy people in emerging markets” to flow into various cities around the world over the past few years, with a special focus on “hotspots” like Berlin. This means much of formerly affordable, trendy neighborhoods like Neukoelln has been snapped up by faraway buyers in Ireland, Norway, or the United States. And this process only gained steam after the 2008 beginning of the euro crisis, as real estate became one of the safest forms of investment in Europe.

Margit Mayer, a professor of political science in Berlin who focuses on gentrification, says, “so many people from all over the world decided that Berlin’s real estate market had enormous development potential, and so they came here and tried to turn it over as quickly as possible.” And Peck points out that it’s no accident that international buyers are targeting Berlin—today’s buyers are well aware of a city’s burgeoning, or fading, reputation. “Cool is much more saleable now than it was in 1975,” he says. Ina recent documentary about gentrification in Berlin, a notorious Norwegian landlord who has bought up over 2,000 buildings in Berlin uses the city’s rampant graffiti as a way of convincing wealthy Italian buyers to purchase an apartment.

Similarly, a Baffler story looked at the city’s commodification of cool.

looked at the city’s commodification of cool.

The idea is to cash in on Berlin’s cachet by branding it as a “Creative City”—but it is also, to judge by what has happened, to gut public services, to sell off public housing, and to strategize about new ways of turning taste into profit. This new Berlin is a city where imaginative expression supports, directly or indirectly, a grand scheme for making a small number of people rich. One of these days, some lucky Berliners and expats will finally attract venture capital from London, Palo Alto, and Boston. But the others—the scenic poor and the clever unemployeds who make the city so attractive—will find it ever more difficult to make ends meet.

These shifts have an impact not just in Berlin but in every city where writers, musicians, artists and the creative class try to settle.