[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”EnEg7SR54tQeApaTB0TxyD3jWfVDaZ1e”]

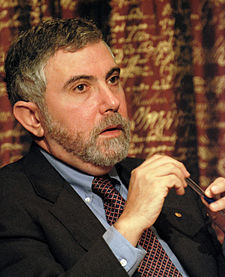

Is the online bookseller a monopoly? A monopsony? I’ll leave the details to the economists, but will concur with the New York Times columnist — and the recent New Republic story — on the company’s danger. The most succinct way to phrase it may be the way Paul Krugman opens today’s column: “Amazon.com, the giant online retailer, has too much power, and it uses that power in ways that hurt America.”

I keep reading how great Amazon is for consumers, and don’t entirely disagree. Wal-Mart sells things cheaply, too, and it’s great for a while, until they start destroying small businesses in your town, putting people out of work, and hiring a few of them back without benefits or medical insurance (many of which are eventually paid by taxpayers). It’s not just about getting a cheap tire, or in Amazon’s case, an e-book for less than it cost the publisher, author and everyone else to produce it.

Here’s Krugman again:

Meanwhile, Amazon’s defenders often digress into paeans to online bookselling, which has indeed been a good thing for many Americans, or testimonials to Amazon customer service — and in case you’re wondering, yes, I have Amazon Prime and use it a lot. But again, so what? The desirability of new technology, or even Amazon’s effective use of that technology, is not the issue. After all, John D. Rockefeller and his associates were pretty good at the oil business, too — but Standard Oil nonetheless had too much power, and public action to curb that power was essential.

After explaining the fight with the Hachette publishers:

After explaining the fight with the Hachette publishers:

So can we trust Amazon not to abuse that power? The Hachette dispute has settled that question: no, we can’t…. Which brings us back to the key question. Don’t tell me that Amazon is giving consumers what they want, or that it has earned its position. What matters is whether it has too much power, and is abusing that power. Well, it does, and it is.

As it gets more power and wealth, why should we think Amazon won’t start gouging consumers as well? At some point, we’ll all be the gazelles.

Paul Krugman believes that he can simply issue proclamations with no evidence, and at most a quick hand-waving justification, and everybody should accept his view as fact, because he’s so obviously more brilliant than everybody else. Apparently you accept that.

More significantly, you seem to emulate his style by asserting that Amazon has reduced the cost of ebooks below the cost of production, without providing any evidence at all to support that claim — let alone the extraordinary proof that such an extraordinary claim demands.

Please provide evidence to support this extraordinary claim.

While we await that, here’s some basic evidence that I see. A sample analysis of cost structures from longtime publisher David Wilk shown here:

http://www.digitalbookworld.com/2013/the-positive-economics-of-ebook-bundling-and-amazons-matchbook/

claims that publishers actually profit more from an ebook sold at half the price of the corresponding paperback. (Authors get a lower royalty in his sample analyses, but since the total of publisher net + author royalty is essentially identical, this would be due to publishers, not distributors, taking money out of authors’ pockets.)

This, of course, because digital distribution eliminates virtually all of the per-unit supply chain costs of both publication and distribution.

And of course, this doesn’t even consider price elasticity — the economic fact that more books will be sold at a lower price — which is a major point that Amazon has been trying to make throughout its negotiations with publishers generally, and the dispute with Hachette, in particular. Lower prices, sell more books, make more profit.

It should be a win/win/win/win: consumers get more books; distributors, publishers and authors each get more profits.

(Without providing a cost analysis, Wilk also indicates that such ebook profits are only slightly below even hardback profits.)

Then consider that ebooks rarely actually sell for just 50% of the paperback price. Rather, they are usually sold for well above 50%, and sometimes cost as much or more than the paperback, itself!

In fact, if we go back two years, here’s an article indicating that an analysis of book prices at Amazon showed that one third of ebooks actually cost more than the corresponding hardback:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2211022/How-bestselling-ebooks-cost-MORE-title-hardback.html

We can thank the major publishers’ illegal price-fixing for that.

Please actually explain and justify (rather than just declaring and waving your hands, without any evidence) why it is that we should believe that Amazon is the party behaving badly here.