[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”V6NmBVYqb2qdo87yWjeHN0SrNINzHk4V”]

NO, this hasn’t become an abstinence-themed blog while you were napping. But I’m struck today by a piece about the joys of waiting for culture, whether it’s a weekly music newspaper or the new singles or LPs that those publications served to announce or assess. No matter what kind of culture you care about, you’ll find something you recognize in this essay by esteemed rock scribe Simon Reynolds in The Pitchfork Review.

Imagine, if you can, or remember, if you’re old enough, a long-ago time when music fans had to wait. Wait for news about music. Wait for reviews that were really previews of music you’d wait even longer to hear. (No teasing tasters, sanctioned streams, or illicit leaks in those days.) Anticipation and delay structured the daily experience of music fandom in the pre-internet era. All music and most information were things you literally got your hands on: they came only in analog form, as tangible objects like records or magazines.

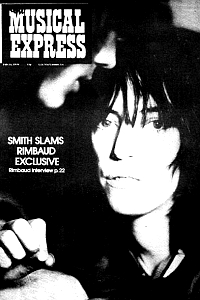

In Britain, where I grew up, the primary source of news, commentary, and critique was the weekly music press: New Musical Express, Melody Maker, Sounds, and Record Mirror. The weeklies were stubbornly solid, slightly grubby things. Nicknamed “inkies” because their pages stained your fingers, they were printed on paper and shipped physically across the country, and also, in smaller quantities and at a more expensive price, to far-flung territories of the globe. How’s this for anticipation and delay? In those days NME and the other papers reached Australia and New Zealand by surface mail and thus arrived several months after they came out in the UK, by which time the British scene would have moved forward a considerable distance.

The essay looks, of course, primarily at the heyday of the British rock press — the NME and Melody Maker primarily — which helped shape the music of the punk and post-punk days, especially, as well as young minds.

But it’s more broadly a piece about the pleasures of anticipation and an analog sensibility. Further down, he writes:

To talk about the systemic virtues of a bygone mode of cultural transmission is to risk scorn. In a culture that idolizes technology and makes secular gods of figures like Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg, it has become inadmissible to talk about change as anything but an a priori positive. And when these changes have taken place within the context of pop music, one also confronts youth’s reflexive patriotism for its own era, the way that hormonal triumphalism meshes with generational self-image to insist that only right now can be the best time. I understand that; I’ve felt that myself. I also know that change is inevitable, irreversible. But I don’t see why one shouldn’t attempt a calm and clear assessment of what’s been lost with the collapse and disappearance of the old ways.

The piece is long and leisurely, and deserves some of the relaxed contemplation it celebrates. Even when Reynolds is writing about the Sex Pistols and the Buzzcocks.