[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”3jo4huPHGtmGS71JRG98EimGVUeNIngq”]

HOW has Western literary culture dealt with the ending of life? How do we see it now? Today guest columnist Lawrence Christon looks at a bundle of complex and painful issues, as recent as the death of Robin Williams and as old as the work of Albert Camus and perhaps Shakespeare. This one is not for the faint of heart.

“ENDGAME,” By Lawrence Christon

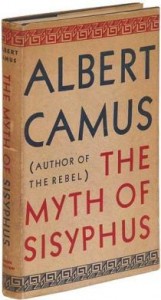

Albert Camus’ famous declaration in “The Myth of Sisyphus,” “There is only one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide,” was addressed to the war-torn, blood-soaked 20th century, “A world of inverted values,” as he put it. But it still rings in ours, most piercingly in the recent death of not just a public figure, but one beloved beyond the dumb show of celebrity.

Out of simple decency and respect for a brilliant and generous-spirited man, not to mention his family, I’m not going to offer any presumptuous speculation on the whys of Robin Williams’ ultimate act, except to suggest that the cause for banishing the shadow between idea and execution, that swift and irreversible decision to make the final leap, is indeed unknowable. And that too demands respect.

You’d hardly think it, though, judging by the outpouring of opinion, and tacit denunciation, by most of the chattering class, that basically comes down to this: If only he’d taken his meds; if only he’d sought help. The fact that he did doesn’t seem to matter. The shock and grief that’s followed a popular figure richly endowed with the gift of laughter is heartfelt and appropriate. But the underlying notion that the canon ‘gainst self-slaughter is based on the precepts of the mental health industry, which now govern our social discourse, seems to me to reduce the scope of what it is to be human.

I’m not tilting my lance at mental health experts, nor do I discount the crucial value of therapy and psychotropic drugs in relieving millions of the horrible confusi on, helplessness and agony of mental disorder. I worked in a mental hospital during the era of Thorazine, Compazine, electroshock therapy and lobotomy, and saw what it is to be a ghostly, fitful remnant of a self, completely unable to function in the normal comings and goings of everyday life.

on, helplessness and agony of mental disorder. I worked in a mental hospital during the era of Thorazine, Compazine, electroshock therapy and lobotomy, and saw what it is to be a ghostly, fitful remnant of a self, completely unable to function in the normal comings and goings of everyday life.

And who cannot feel the mortal anguish underlying author David Foster Wallace’s words when he began his 1998 essay, “The Depressed Person,” by observing, “The depressed person was in terrible and unceasing emotional pain, and the impossibility of sharing or articulating this pain was itself a component of the pain and a contributing factor in its essential horror.” Wallace capitulated to that horror by taking his life in 2008.

For most of recorded history, philosophy and the arts have reflected both the mutability and constancy of human experience. Suicide, in a social context, was usually seen as an act of redemption for dishonor or disgrace, as when the Roman fell on his sword, or a Japanese committed seppuku. In an excellent piece that ran August 18 in the Los Angles Times, theater critic Charles McNulty took up the theme by contrasting epochs in drama, citing the conditions that made Antigone’s suicide differ from Willy Loman’s, for example. All roads to modernity lead through, Hamlet, however, about whom McNulty writes:

Suicidal preoccupation in Hamlet is paradoxically a source of his humanity. What draws us to him is the eloquence with which he articulates hidden feelings that most sentient human beings have shared at one point or another in their long and sometimes overwhelming journey. Most of us, thank heaven, won’t commit suicide, but one reason suicides fascinate and appall us is that they raise fears about the boundary between black thoughts and irrevocable action.

But something happened beginning in the late 19th century and continuing into ours: The revolutions and discoveries in art were nothing compared to the phenomenal advances made by science and technology, in which anything goes as long as you can prove it. Science, not philosophy or the intuitions of art, became the arbiter and ultimate authority on truth. The unintended byproduct, which is still with us, is the assumption that what is not demonstrable is not true.

Renaissance man, the measure of all things, shrank to a consumer, a taker of selfies. The poet, as one critic noted, has been reduced to making “mere facticity a secular creed.” Hart Crane’s line, “As silent as a mirror is believed/Realities pass in silence by,” makes no sense to our modern, pragmatic mind. Hence our discomfort with the mystery of the human heart, our conversion of ineffable mind into chemically tractable brain. Not every psychotherapist feels this way, incidentally. Well-respected L.A.-based Dr. Terrence McBride e-mails, “…all our emotions, moods and behavior are not due to brain chemistry. Mostly, it’s the other way around.”

My younger brother, who had AIDS, opened his veins in a bathtub of our shared apartment. Afterwards, a nurse attending him said, “His needs were greater than yours.” Who asked you? I thought angrily. Since when does death have to answer to a banal hierarchy of needs? But I respected my brother’s choice, even as I cleaned up his blood.

Instead of complaining and pointing a moral, why can’t we just mourn the dead and leave them in the peace they so desperately craved?