[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”Scx4VCooDHhyWVBgymxHy3X9hGhGh8Y4″]

LATER this week, one of our spring rituals arrives: The Ojai Music Festival kicks off on Thursday. It’s always a good time up there, and this year we’re doubly excited because of the artistic directorship by pianist Jeremy Denk, one of my generation’s most imaginative players, a gifted writer of prose on his blog and elsewhere, and a great advocate for Ives.

There’s always a lot to see at Ojai, but for now we want to talk about two performances by longtime jazz pianist and downtown experimentalist Uri Caine.

California’s lovely and gentle Ojai Valley does not put us in the mind of the brooding Austrian Gustav Mahler, but that’s part of what Caine has cooked up for the festival. He’s developed a cottage industry interpreting classical composers in an improvised setting – Schumann, Beethoven, Bach, even Vivaldi – and he’ll present Mahler Re-Imagined as part of the festival’s Thursday night opening concert. (Caine will also interpret Gershwin Friday night with his sextet.)

Caine is aware that Mahler is not known for being light-hearted, and his music – even compared to other classical figures – doesn’t exactly swing. With all that rubato and agony, he’d not be the first to come to mind first for a jazz-oriented treatment. But he’s more complicated than his reputation, according to Caine.

“There are a lot of different traditions happening in Mahler,” Caine told me from a tour through Spain. “Mahler is using all these elements, and as improvisers we use them as jumping-off points. Bohemian folk music, military music he heard growing up, funeral marches, and the music he studied and conducted – Wagner, Mozart. He could be simple and folk-like or very violent, very merry and very bleak.”

Mahler’s synthesis of different styles confused people at the time, Caine says, but his fragments and allusions make him in some ways a man for our postmodern times. Of course, the composer’s work is still not universally loved. “One thing people don’t always like in Mahler is that he goes off on some many tangents; he’s trying to develop so many different themes. As improvisers we do the same thing.

Caine’s taste is catholic and wide-ranging, but that doesn’t mean he treats every composer’s work the same way. In fact, he insists that he pays enormous attention to the differences between each figure. “It has a lot to do with listening to the music, and then, like a student, trying to understand it. Letting the impressions dictate where you go with it,” observing the underlying structure, and then seeing what his bandmates respond to in their improvisations.

And while he knows some classical folk – musicians, audiences and critics alike – don’t see improvisation and classical music have anything to do with each other, he disagrees vehemently. “There is a tradition of improvisation in classical music that’s atrophied now,” he says. But Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Chopin were great improvisers. “In the old days before records, people were basically writing out piano improvisations.” Cadenzas, especially, were typically improvised in concert. “Sometimes when modern composers try their own cadenzas, people are scandalized. But that’s the point!”

Still, the tradition Caine and his players work in – improvising over chord changes – comes more directly from jazz; he’s especially impressed with the styles developed by John Coltrane (with its “swirling” quality and sheer speed), Miles Davis (for its understatement and apparent simplicity) and tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson (for its swing and sense of humor.)

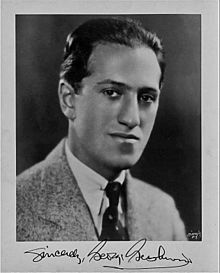

Far closer to jazz than Mahler is the work of George Gershwin. Caine will also be reimagining the music of Gershwin, including Rhapsody In Blue, at Ojai. Gershwin was a bit like Mahler, he says, a synthesizer who brought a number of styles together – “Rachmaninoff, klezmer with the clarinet, a bit of Latin at the end.

Like a lot of jazz musicians, Caine spent his early years jamming on the changes to “I Got Rhythm” and other Gershwin songs, so it was natural for him to come back to one of his earliest sources.

“He was an amazing pianist, able to absorb ragtime and a lot of the New York players. You hear stories of him as a teenager, working for Irving Berlin – he was already a prodigy.” He differed from some of his contemporary songwriters in the Tin Pan Alley and Broadway orbits in being more steeped in jazz harmony, and by “self-consciously imitating a lot of classical composers – the Russians, the French – with added 6ths, added 9ths, moving by major 3rds.” And of course, much of his music drips with the blues.

Caine laments that Gershwin, who left so many great songs – “They Can’t Take That Away From Me” and “Our Love is Here to Stay” are two favorites — died so young, at the age of 38 from a brain tumor.

“He lived long enough to play tennis with Arnold Schoenberg,” Caine says. The Austrian composer, he imagines, “probably looked at George Gershwin and said, ‘America is an amazing country.’ “

CultureCrash looks forward to seeing you at Ojai.