[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”1HoMw0eKbPzQBS6WAPogsGZlqRRM0XrN”]

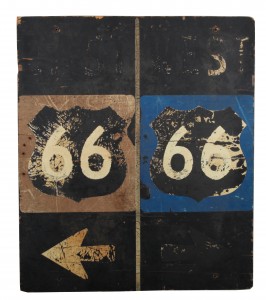

Collection of Steve Rider

WELL, that sure was an unexpected pleasure. I thought I knew a bit about Route 66, but there are apparently dimensions to the legendary historic highway I’d not considered. The press preview I walked out of this morning left me thinking that this medium-sized exhibit at the Autry was the best social-history show I’ve seen in many moons. For enthusiasts of California history, it’s simply essential. (The show opens on Sunday June 8.)

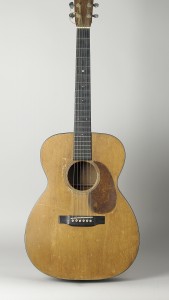

The show is structured chronologically, mostly, but tells a larger story of the planning, growth, packaging, decline and revival of the 2,400-mile long thoroughfare. Dating back to the age of railroads, to the turns of the century “Good Roads” movement which saw the spread of bicycles, and an enlarged building role for the federal government (roads have previously often been privately established), Route 66 was initiated in 1926. Before long it was known as America’s Main Street. The Depression came to associate it with the down-and-out — there’s some attention to the books of Steinbeck, the photography of Dorothea Lange, and the music of Woody Guthrie, whose battered Martin guitar is part of the exhibit. The New Deal helped it get paved.

Postwar car culture, motels, neon advertising, and Burma-Shave ads transformed it. Dozens of “sundown towns” in which black people were not welcome after dark means a color line ran right through the middle of the highway. The Beat generation loved Route 66, and Kerouac’s original scroll for On the Road, which has never been shown in Los Angeles, is part of the show. (Curator Jeffrey Richardson said that for all his pharmaceutical enthusiasms, Keruoac write it on nothing stronger than coffee. Richardson, who led the tour with great energy, seemed quite familiar with caffeine, so I’m willing to take him at his word.)

Oklahoma’s Ed Ruscha, who seems himself like a figure from Route 66 myth, photographed its gas stations, which were revisited by a contemporary photographer; both are part of the show.

But just as the road was becoming a tourist draw and a legend of Americana, the interstate highway system, destinations like Disney World and Vegas, cheap air travel, and a diminishing sense of place conspired to undercut it. The myth tarnished; the highway began to literally come apart, as its asphalt crumbled. Route 66 ceased to be an official national highway. But for reasons I had not considered, it began to come back.

But just as the road was becoming a tourist draw and a legend of Americana, the interstate highway system, destinations like Disney World and Vegas, cheap air travel, and a diminishing sense of place conspired to undercut it. The myth tarnished; the highway began to literally come apart, as its asphalt crumbled. Route 66 ceased to be an official national highway. But for reasons I had not considered, it began to come back.

You probably knew some of this stuff, but the details and artifacts are fascinating, especially the way it fits into the larger contours of 20th century history. I could go on, about oil boomtowns and Roy Rogers and Jackson Pollock and the LAPD’s “bum blockade,” but I’ll stop here.

Even if you’re sick to death of the Bobby Troup song (and like the Depeche Mode cover even less), this is one to see.