[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”8lG1gx076ac8sMEbh9E4fK0epPYBWHeb”]

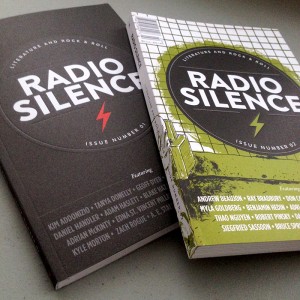

THERE is a great new-ish journal out of San Franscisco that not only has the right idea, it has the follow-through. Radio Silence includes work by established elders (peerless short story writer Tobias Wolff), an interview with Lucinda Williams, and appearances by Carrie Brownstein, Rick Moody, even F. Scott Fitzgerald. It’s all presented as a crisp and handsome ode to print, with smart graphic design, and the Radio Silence gang, headed by editor Dan Stone (who once made documentaries for the NEA), recently began an online version. (Neko Case, by the way, is on the board of directors.) It’s got all kinds of pieces — poetry, interviews, odd bits of memoir — and they are all eminently readable.

(Neko Case, by the way, is on the board of directors.) It’s got all kinds of pieces — poetry, interviews, odd bits of memoir — and they are all eminently readable.

Rather than go on about how much I love Radio Silence — rock music, literature, and the writing about both, are among the subjects that drove me into journalism, and this journal reminds me why — I corresponded with Dan Stone about the venture. Our conversation is below.

ST: What made you want to start a new magazine devoted to “Literature and Rock & Roll,” especially in such a tough economic climate?

DS: When I started putting together Radio Silence a couple of years ago, I had no illusions that launching a magazine was a wise business move. Magazines seem to be closing up shop almost weekly. The old models are broken. But I have ambitions, maybe foolishly, that we can redefine what a magazine can be, and that we can contribute something worthwhile to the cultural discourse. We’re approaching things differently, not relying on advertising revenue; instead, we trust that smart, engaging, accessible content, as well as artistic and editorial integrity, will attract a supportive readership. Along with the publication, we put on live events with writers and musicians. And as a 501(c)3 nonprofit, we set aside a portion of our revenue to buy books and musical instruments for kids. I’m confident that we can turn Radio Silence into something lasting and important. We’re not there yet, but we’re working hard at it.

I probably also have an appetite for punishment, and certainly for poverty. But the simple reason I started Radio Silence is that I’m a lover of literature and music, as so many of us are. Those are two areas of art that influence each other in many ways. I didn’t know of another publication that combined the two, and it has proven to be a natural and exciting pairing.

Give us a sense of your own taste in music and writing. Who are a few touchstones for you?

Man, that’s always the toughest question. My musical tastes are all over the place—lately, for example, I’ve been listening to a lot of Willie Nelson and Minor Threat. At the moment, I’m listening to Duke Ellington’s Piano Reflections, which is great for working. Other favorites include Buddy Holly, Tom Waits, Loretta Lynn, Elvis Costello, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and newer bands like Typhoon, Thee Oh Sees, Father John Misty, and Mikal Cronin.

Book-wise, I most recently read Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons, Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage, which is wickedly funny, and now I’m starting Richard Hell’s memoir, I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp. I’m also a big poetry fan, and of course I love fiction.

You include a few writers – Edna St. Vincent Millay, Siegfried Sassoon, Scott Fitzgerald – who predate Chuck Berry’s first singles and Elvis’s Sun Sessions. How do they fit in?

It would be fun to argue why some of that early 20th-century literature is in the same vein as rock music, and maybe it is, but really, Radio Silence focuses on both literature and rock & roll—sometimes considering the two mediums together, and sometimes on their own.

As you pointed out, we publish fiction and poetry by writers from the past, as well as new stuff. With the older classic material, we try to include lesser-known work. The aim is both to help revive writers we admire, who may have drifted from the attention of the general public, and to bring to light more obscure work by someone well known like Fitzgerald. The story we published by him was “Winter Dreams,” but we went to the Library of Congress and found the original 1922 magazine version, which differed in several interesting ways from the later book appearance of the story. For one, Fitzgerald stripped a couple of passages from that first version to use in The Great Gatsby.

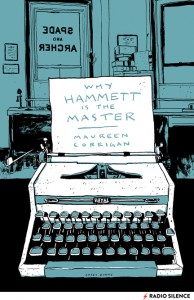

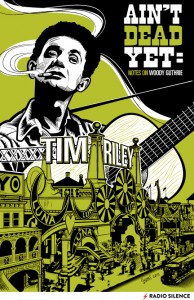

Your graphic design and artwork is sharp and distinctive. What kind of design aesthetic are you going for?

Thanks for noticing that. We’ve got a super-talented design team led by our Art Director, Casey Burns (who also works for Victoria’s Secret), and our Design Director, Brandon Herring (who works at Google). Luckily, those guys share my aesthetic—clean, strong, classic, memorable. We use a two-color design, and for each piece of writing, we commission what we call a “rock poster”—basically a full-page illustration that serves as a cover for the essay, story, interview, or poem.

You’re from the same city and the same generation at Dave Eggers. Has the Believer/ McSweeney’s empire inspired or influenced what you do at all?

I’m a big admirer of what McSweeney’s has accomplished in San Francisco, essentially reviving a once-great literary culture that was devolving into stale literary-museum status. They do great work, and the scene has really come to life in the decade since The Believer launched. I subscribe to most of their titles, and I even live two doors down from their headquarters, so I can feel the McSweeney’s vibrations pulsing through my living room wall. Or maybe that’s the rock club next door. But whatever it is, it’s inspiring. Many of the McSweeney’s and 826 Valencia staff members have been wonderfully supportive and encouraging of what we’re doing with Radio Silence.

However, it can be a tricky thing to launch a magazine in a town ruled by a power as impressive as McSweeney’s—you have to distinguish what you’re creating as something separate and unique. So while they’ve been inspiring neighbors, I’ve been careful to identify Radio Silence as a clearly independent enterprise.

Describe a few pieces you’re especially proud to have published. Jim White’s essay “Superwhite,” a bizarre and well-written tale that includes cameos by David Byrne, was nominated for a Pushcart, I think.

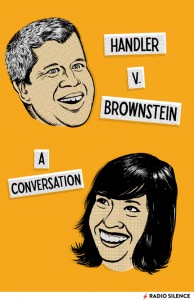

I’m excited about a bunch of the pieces running this spring and summer in our digital edition—many of which will be included in our annual autumn print issue. One is a memoir by Lucinda Williams that we recorded at her house in LA. She talks a lot about her dad, Miller Williams, the great poet, and she describes chasing Flannery O’Connor’s peacocks as a little girl. We’ve also got a deliciously naughty short story by my favorite living playwright, David Ives—imagine Jane Austen, a hooker, a horse-drawn carriage, and lewd sex, then imagine that someone combined those elements into a moving and sad and beautiful tale. We also just published a conversation between two of the funniest and most original contemporary artists, Daniel Handler and Carrie Brownstein.

You’ve recently started an online version of Radio Silence. What motivated that, and does that mean you won’t be putting out a print version

We’re still committed to print. We look at our print magazine as our turntable-and-vinyl, the sort of thing you want to sit down and spend time with, put it on your shelf or lend to friends, go back to it, let it age. But we also just launched a monthly digital edition, which allows us to explore the possibilities offered by mobile and web, such as embedding audio, films, and photographs in many of the pieces. Each medium has its own strengths—print has that lovely tactile intimacy, and if it’s good stuff, you keep it; digital is ephemeral, adaptable, and convenient.

Many literary and artistic ventures are struggling these days. How do you manage to publish Radio Silence?

So far, with a lot of sacrifice and commitment from an unpaid staff of ten people. While we do pay our contributors, no one on our staff, including me, has been paid a dime for our work. And although we hope to change that through growth and fundraising, it’s a pretty great way to launch a magazine. It reminds us—sometimes painfully—that we’re not doing this for riches, that there are more important things than a paycheck, and it feels good at the end of the day to be committed to something purely for the love of it.