[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”dHp9P0RkCZ3f7i5yDaz9hEWZeYiwNVGG”]

WHAT happens to us when we read on an electronic device? Does it alter our ability to connect with a nuanced piece of fiction? Two recent stories get into these questions from opposite angles. I wrote about this a few weeks ago, and the conversation still rages.

This reported story from the Washington Post makes clear that there’s a price to be paid for the speed and efficiency that comes with digital skimming. The piece on “serious reading” quotes Tufts neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf.

If the rise of nonstop cable TV news gave the world a culture of sound bites, the Internet, Wolf said, is bringing about an eye byte culture. Time spent online — on desktop and mobile devices — was expected to top five hours per day in 2013 for U.S. adults, according to eMarketer, which tracks digital behavior. That’s up from three hours in 2010.

Word lovers and scientists have called for a “slow reading” movement, taking a branding cue from the “slow food” movement. They are battling not just cursory sentence galloping but the constant social network and e-mail temptations that lurk on our gadgets — the bings and dings that interrupt “Call me Ishmael.”

Overall, this wide-ranging story confirms my sense — which was at the back of my mind writing this piece — that reading an old-fashioned bound book is different in some important ways than reading online or on a device that takes you out of the narrative with links, ads, whatever. I don’t deny that digital technology offers plenty of benefits. But there’s a price to be paid for these advances, and as with a lot of new technology, that price is often invisible and its consequences sometimes unintended.

A Guardian column rebuts the point of view of people like Nicholas Carr, Sherry Turkle, and yours truly. Steven Poole writes:

In our culture of excitable neuroscientism a lot of such arguments employ the sexy word “brain” and so sound scientifically objective, but they are really socio-cultural arguments. No doubt there are many kinds of task-specific neural developments (ie “brain” types) that have been lost in the mists of evolutionary time, and whose absence we have no reason to regret. Not many people in advanced industrial societies today, for example, grow up developing the mental skills required to kill tasty large mammals with a well-hurled spear. But we don’t read hand-wringing stories about how we have lost the antelope-hunting brain. So there needs to be a further demonstration that the “deep-reading brain” is something worth valuing. And this is never going to be a (neuro)scientific argument; it’s a cultural argument.

Poole makes some good points. I conceded in my story that I am no scientist and that my preference for c ertain kinds of reading is indeed cultural. But a lot of what we promote or criticize is “cultural” behavior. If we want to have a culture, we have to keep doing that. So I’ll urge folks to read the Guardian piece, but stand my ground here.

ertain kinds of reading is indeed cultural. But a lot of what we promote or criticize is “cultural” behavior. If we want to have a culture, we have to keep doing that. So I’ll urge folks to read the Guardian piece, but stand my ground here.

ALSO: The fate of libraries is an important issue for me, and not just because my wife runs a school library. It does not cheer me to hear of thousands of book, including many volumes of art history, ending up in a dumpster on the campus of the University of New Hampshire. Report here.

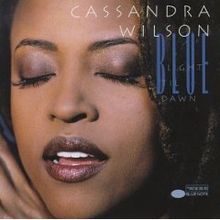

FINALLY: I should end the week’s posts with something to be grateful for. One of the best jazz albums of the ’90s, Cassandra Wilson’s Blue Light Til Dawn, is getting a 20th anniversary reissue, with some live tracks. I wore out this one New Moon Daughter at the time; both records found the common ground between jazz, Delta blues and folk.

I love the ballads on the record, including “You Don’t Know What Love Is,” but here is her cover of the Robert Johnson blues, “Hellhound on My Trail.” Wilson continues to be a vital performer, and is touring in the US and Europe behind the reissue.